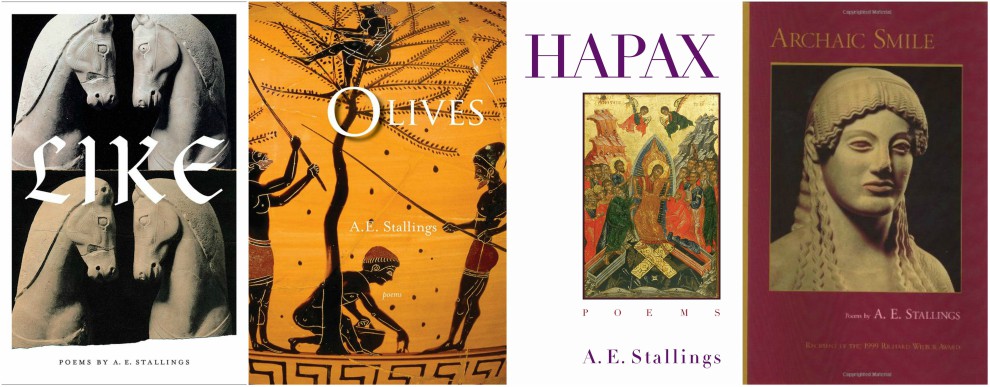

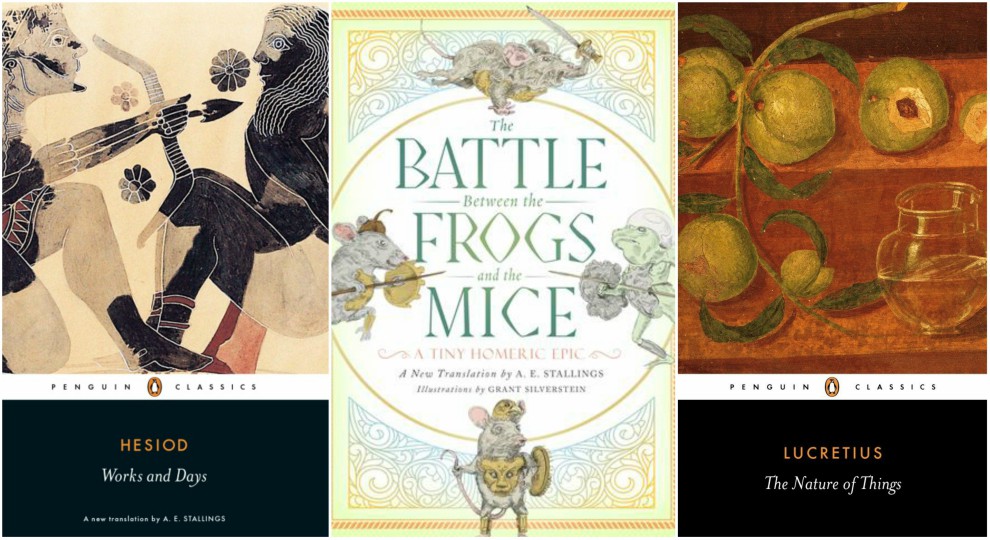

A. E. Stallings is a U.S.-born poet, translator, and critic who has lived in Greece since 1999. She has published four collections, most recently Like (with Farrar Straus, and Giroux), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; and verse translations of Lucretius, The Nature of Things, and Hesiod, Works and Days (with Penguin Classics), as well as an illustrated verse translation of the pseudo-Homeric The Battle Between the Frogs and the Mice (Paul Dry Books). Her criticism and essays appear widely, including in The Hudson Review, The Sewanee Review, The Wall Street Journal and Times Literary Supplement. She has received grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, United States Artists, and the MacArthur Foundation. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She lives in Athens with her husband, the journalist John Psaropoulos, and their two children.

A. E Stallings spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes her poetry touches upon, noting that “subjects that come up repeatedly include Greek mythology, history, the underworld, and the domestic sphere, marriage and motherhood”, while commenting on the way her “Greek mythology has always been a very domestic world” as well as on the fact that “living in Greece for the past 20 years has no doubt changed [her] relationship to Greek myth and history”.

Asked about the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits, she explains that “poetry connects the dead with the unborn” with “prophecy being one of the aspects of poetry”. She concludes that “in a time of border anxiety (and walls), translation becomes that much more important” and that “it is an exciting time to be translating, especially given the richness of modern and contemporary Greek poetry”.

Your poetry collections are highly praised and earned you a nomination of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2019. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

Probably there are themes I am not aware of—one theme that was brought to my attention by an interviewer that I hadn’t been aware of was “discord.” Subjects that come up repeatedly include Greek mythology, history, the underworld, and the domestic sphere, marriage and motherhood. Currently I suppose I am also trying to grapple with grief about the natural world—the beauties that were our birthright, but which might not be passed down to our children or our children’s children. I am not sure poetry is the best place for this, though, and am still wrestling with it.

Your poetry seems to combine contemporary themes with the images and history of ancient literature, the haunting beauty of Greek myth with the daily occupations of modern life. How is this blend achieved in your work?

Ah! An overlap with my answer to the previous question. My Greek mythology has always been a very domestic world, even the underworld or the labyrinth are domestic interiors. I think perhaps this comes from a childhood spent deep in fairytales and books of myths, and the way a child’s imagination doesn’t differentiate between the “real” world and the world of dreams. Maybe. Living in Greece for the past 20 years has no doubt changed my relationship to Greek myth and history, as the Greek language itself is a kind of background, or landscape in the poems.

“Rhyme is a sort of echolocation—you speak out into the world, and it answers back to you. But meter is something more internal, it is more about listening to some internal voice”. What role does language play in your writings?

I write almost exclusively in received forms (sonnets, iambic pentameter, etc.); exclusively, if you consider that when I am writing free verse or a prose poem, I am very aware of these as “forms” with their own traditions and constraints. I do believe that embracing a form or a constraint is about embracing a freedom rather than a limitation. You are freed somewhat from your own intentions, and can listen to something outside of yourself. Rhyme gives permission to let go of reason. Meter also works in a very visceral rather than intellectual way. And most of the poems I really love are also within this musical tradition. My advice is to write what you like rather than what is fashionable.

What about translation? Which were the main challenges of translating Lucretius and Hesiod in English?

I had very little experience as a translator when I embarked on the Lucretius in my 20s. So I learned by doing. The Latin is sometimes difficult and vague, and deals with difficult subjects. I started in a long line (fourteeners, similar to the Greek political meter) to encompass the hexameter Latin line without having to drop things out. I also started out with more slant rhyme. But as I came to understand the poem better, and to get a hang of what I was doing, I embraced the suggestion of making the rhyme tighter also. Rhymed couplets (the original is not rhymed, of course) helped me to look at larger units than the line, which was important in understanding the poem. For Lucretius (expounding Epicurean philosophy in verse, when Epicurus was himself against verse), poetry was the honey that helped the medicine go down. I started to think of rhyme as the honey of English poetry. I suppose it was also a lesson in stamina, just plugging along every day until the 7000 + lines were done. I never skip around, going to the “good” parts first, because I would never get through the connective parts of the poem, the recitatives that make the arias possible. I did learn a lot about the long poem, and about philosophy I think.

The Hesiod (Works and Days) was much shorter (only 900 lines), but I was responsible for more of the introductory material. Although the Hesiod was also in dactylic hexameter, in this case I went to a five beat line in English. Greek is swifter than Latin, and less convoluted syntactically. It was fascinating to be working on the Hesiod during the Greek economic (and later migrant) crisis, as it turned out to be such a contemporary work, concerned with debt, hunger, profit, work, justice, corruption. Many of the words were absolutely the same as they are in modern Greek. And Hesiod himself is the son of economic migrants who came to Greece from Asia Minor (now Turkey), not far from Lesbos.

I have also translated a book of the Erotokritos (in rhymed couplets). Perhaps I will someday return to that and do more.

Renowned translator Karen Emmerich has claimed that when translating from a so-called ‘minor’ to a so-called ‘major’ language or literature, translators sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power? Where does the role and responsibility lie?

I think that is true, and I am interested in the ethics of translation. For a classical text such as Hesiod, there are already many translations out there, so it is perhaps of less import. But I do also translate modern and contemporary Greek literature, and I am aware of being a kind of ambassador. I suppose one of the responsibilities is accuracy (and, in the case of a living poet, consulting with them about their own wishes, their own feedback). Another responsibility is to get across the texture and formal choices—if a poem is a sonnet in the original, every effort should be made for it to be sonnet-like in the target language. A third responsibility is in the framing of the translation: in introduction, notes, etc. The more you know about a literary tradition, the better you will be able to understand things such as allusions, quotations, and conversation with other literary works. All of this responsibility falls on the translator. Also, trying to bring lesser-known works to the attention of the audience. In the case of English-speaking writers, this is even more important because so little world literature gets translated into English, while English is at the same time a global language.

Back to poetry. What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits? Could poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Yes, it can, and it should. Poetry connects the dead with the unborn. Prophecy is one of the aspects of poetry. I have been thinking a lot about the genre of prophecy—it shows up in Hesiod’s Works and Days, for instance, and there is an element of it in Lucretius. The idea isn’t necessarily to know or show the future, but to show the possible futures if we do not change our behavior and relationship with the world. I think of Richard Wilbur’s “Advice to a Prophet” often. I think this is also my attraction to the Underworld (or, in a more recent poem, the Valley of Lost Things on the Moon), that it is a place where anything may be imagined and explored. I think this is also the pattern of “negatives” and negations in poetry: that you can have your cake and eat it too. A poem that talks about “nothing” is making that nothing a something.

What about contemporary Greek poetry? Does the new generation of Greek poets have the potential to attract readers beyond national borders?

I am no expert on contemporary Greek poetry, but it does seem to me there is a lot of exciting work going on, and that there is an increase in interest in the US and in the UK. Three English-language (or dual language) anthologies came out about poetry of the “crisis”: Crisis, Futures, and Austerity Measures. I have translated recent work by Chloe Koutsombeli, Panayotis Ionnides, Stamatis Polenakis, Katerina Iliopoulou, and Dimitra Kotoula. I was also honored recently to participate in a reading (at the Poets’ Agora) with Yannis Doukas and Pavlina Marvin. I was also much saddened by the death of Katerina Anghellaki-Rooke some weeks ago: she was such an important figure of friendship between Greek and Anglophone poetry, and an important translator herself as well as a major poet. And now we have lost the inestimable Kiki Dimoula as well. In a time of border anxiety (and walls), translation becomes that much more important. I think there is a lot of interest in new work from other languages. Translation itself is starting to get its due as not as a secondary art, but a primary one. It is an exciting time to be translating, especially given the richness of modern and contemporary Greek poetry.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE