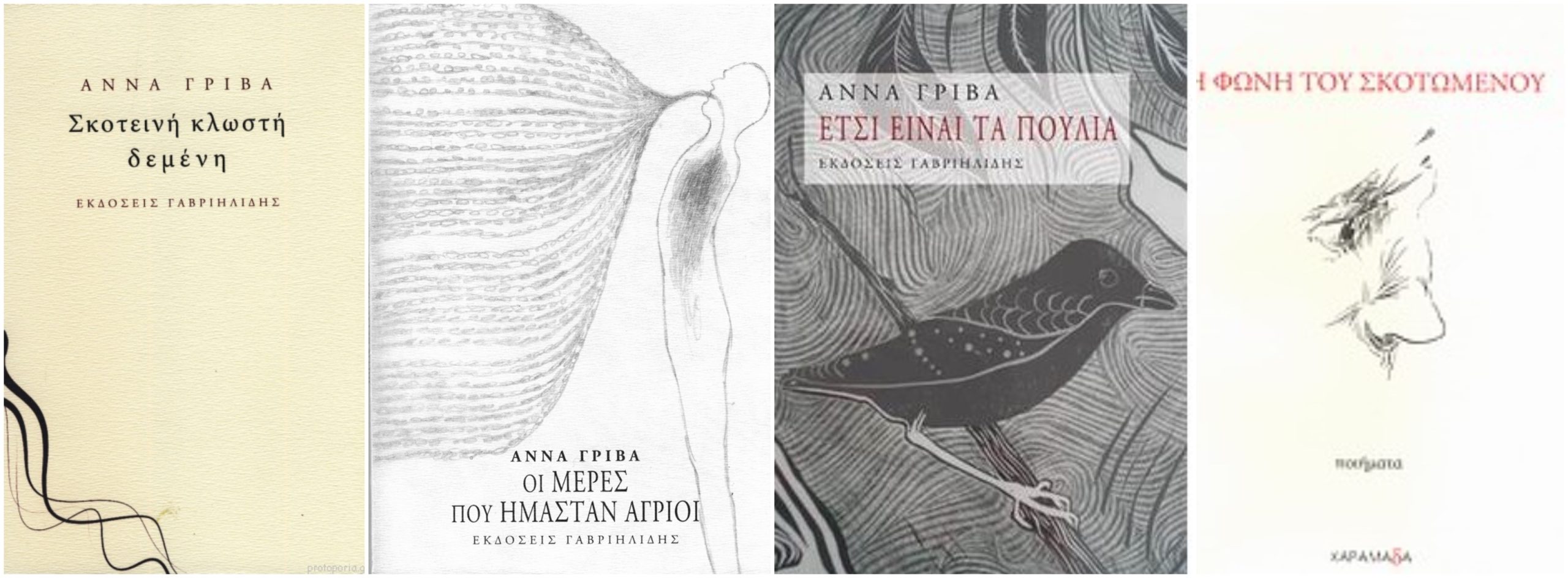

Anna Griva was born in Athens in 1985 and studied Greek in Athens and History of Literature in Rome. She has published four books of poetry. Her latest book is titled Dark Tied Thread (Gavriilidis, 2017). Her poetry appeared in English, French, Italian, German, Spanish and Turkish.

Anna Griva spoke to Reading Greece* about the main issues her poetry touches upon noting that “a binding thread that unites all my books is my love for the natural environment, the animals and the trees, as well as my admiration for the magical influence of legends and myths”. She comments that “ancient myths constitute an inexhaustible source for thought” given that “the precision, with which ancient myths chronicle human nature and cosmic forces, is truly amazing”. As for language, she explains that “poetry holds the same power as music: it arouses primordial, unmediated emotions”, and adds that “the musicality of language may dictate images and senses, while it may imperceptibly introduce readers to a different world, where everything is transparent and lucid, and meanings unfold and are interpreted in a deeply esoteric way”.

You have published four poetry collections so far. Which are the main issues revolves around?

Each of my books focuses on a different issue. In my first poetry collection The voice of a dead man [Η φωνή του σκοτωμένου, 2010] , a man returns to life and narrates his past as a dark fairy tale, trying to exorcise, though a magic kind of language, the heavy shadow of death. My second poetry collection The days we were wild [Οι μέρες που ήμασταν άγριοι, 2012] refers to the relation of men with nature, instincts and the animal part of themselves. The third collection So are the birds [Έτσι είναι τα πουλιά, 2015] deals with memory and its power to determine our lives, whether it relates to personal memories and people we have lost or to collective memory as recorded in legends and traditions. In my forth poetry collection Dark Tied Thread [Σκοτεινή κλωστή δεμένη, 2017], mythical heroes narrate their stories in a way that sheds light on a different aspect of their tragic fate, which is our common fate.

I my new book titled Demonic Creatures, to be published late this year by Melani Editions, I focus on various historical figures, in whom I discern a demonic divine nature. And it’s mainly women who play a pivotal role, revealing this invisible, nonperishable aspect of the world and the close connection to nature. In any case, there is a binding thread that unites all my books, and this is my love for the natural environment, the animals and the trees, as well as my admiration for the magical influence of legends and myths.

In your latest book Dark Tied Thread, your poetry converses with ancient myths and the ancient Greek poetry in an attempt to poetically restructure the psyche of ancient heroes. How does this immersion in the ancient world relate to the contemporary one?

Ancient myths constitute an inexhaustible source for thought, which explains why artists are interested in them no matter how many centuries have passed by. The precision, with which ancient myths chronicle human nature and cosmic forces is truly amazing; and I am deeply touched by this combination of mythical discourse and philosophical precision. And of course, the ancient world has so much to teach us, such as the balance between meditation and ecstasy, between earthly pleasures and the contemplation over metaphysical issues, a balance Christianity disrupted and Renaissance restored. In my book Dark Tied Thread, Hecuba could be a contemporary immigrant, Achilles a warrior who loves peace and earthly happiness, although he is obliged to live in another way, Antigone a girl forced to grow up prematurely and lose her childhood.

Your poetry is characterized by an intense lyricism, an exquisite musicality. What role does language play in your writings?

I really love my language. I believe that all writers feel the same, as painters love their colors or sculptors the materials through which their shapes take form. A writer’s material is words, and he/she knows that he/she has to bring their most subtle tones into the surface. Especially poets, who express themselves in the most abstract way, should be more than careful since whatever inaccuracy, whatever weakness becomes easily discernible and may destroy the whole. I am so touched to read Homer in the prototype and realize that the words are after all the ones I myself use and listen around me.

In a way, poetry holds the same power as music: it arouses primordial, unmediated emotions. Yet, unlike music, logical processing is not often necessary. The musicality of language may dictate images and senses, while it may imperceptibly introduce readers to a different world, where everything is transparent and lucid, and meanings unfold and are interpreted in a deeply esoteric way. There are poems that I have read and changed my whole perspective about the world, being totally revealing for me. As for lyricism, which comes from the Greek word ‘lyre’, it is in my mind related to the musical texture of the poetic language: a poem plays a chord in the lyre of our soul. Meaning and form should harmoniously co-exist, in the same way as the mind and emotion.

In her review of the book, Asimina Xirogianni comments that “what is at stake at every form of art is whether it leads to something new, opening up to perspectives unimaginable up to then”. What is the relation of poetry to the world it inhabits? Can poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Poetry, as all forms of human activity, inevitable relates to the world it was created in. We receive stimuli that we make good use of by transforming them. Unless this transformation takes place, the result is insufficient, demoted to a dull, superficial recording of the existing in a denunciatory tone. In Zibaldone, Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi claimed that what poetry needs is a convincing lie. According to Leopoldi, this lie does in no way constitute a deception but rather the creation of a reality, through the poetic language, which convinces the reader that things are or may be that way. It’s this lie of poetry that helps safeguard the potentiality of reality, the chance that the dreams, expectations and intuitions of the most sensitive human beings are actually real.

How would you comment on poetic creation in the era of online communication? What role do the social media play in the promotion of young poets?

The social media and online communication in this respect have exerted a great influence on all aspects of our life. I reckon that open access to information may only play a positive role. Of course an artist has to be careful not to “circulate” his/her works unsparingly. There should always be a certain amount of prudence so that a reader understands that every creation is the result of hard work and should thus be treated accordingly.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek writers is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. How do they relate to world literature? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

Indeed, modern Greek poetry has been influenced by the international artistic environment, which is inevitable given that young people speak foreign languages, travel, migrate. I would say that foreign poets have exerted a much more significant influence than the Greek poetic tradition. This has both a positive and a negative aspect: on the one hand Greek poetry forms part of a multicultural reality; yet there is a certain alienation from important works of the Greek language and especially Classic Letters. Poets abroad seem to love Classic Letters more than Greek poets. And this certainly has to do with the fact that the field has been undermined in the Greek educational system during the last few years. In any case, we should always think of the national as global and the global as national.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE