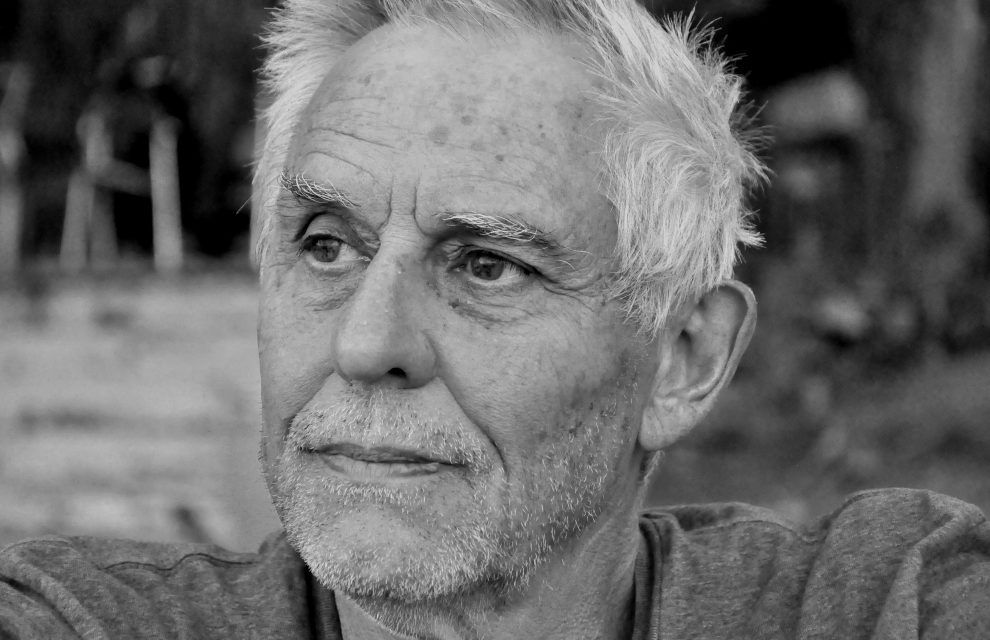

Aris Maragkopoulos (b. Athens, 1948) is a Greek writer, literary critic and translator. He studied History and Archaeology at the University of Athens, History of Art and Archaeology at the University of Paris I Pantheon-Sorbonne. He has published more than 20 books (novels, short stories, essays, photo collections). His more widely read novels thus far are: Obsession with Spring (2006-2009), The Slap-tree (2012) and his «French» novel Paul et Laura, tableau d’après nature (2016). Apart from their literary merits the above books have ignited a certain discussion in Greece as to the possible ways of narrating history in literature.

Maragkopoulos is considered an authority on James Joyce in Greece. He has written three books and many articles on the matter. His most important study, Ulysses, A reader’s guide is an attempt to re-read James Joyce’s Ulysses through affinities to its Homeric counterpart, the Odyssey. His Joycean studies have influenced his critical reading of Greek modern and contemporary prose: his relevant writings over the years place emphatically Greek literature in the frame of the European literary canon. He has also translated into Greek, Irish writers such as Jonathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels), Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe), James Joyce (Giacomo Joyce, excerpts from Ulysses), as well as Henry James (Washington Square, The Wings of the Dove), Marguerite Duras (Moderato Cantabile), Honoré de Balzac (Sarrasine) and some French essayists.

Aris Maragkopoulos has served for two consecutive terms as executive secretary of the Hellenic Authors’ Society. His novel Love, Gardens, Ingratitude has been translated into Serbian, Obsession with Spring into Turkish, his short novel Nostalgic Clone into English. Three of his books have been shortlisted for the National Literary Award: Love, Gardens, Ingratitude (2002), Paul et Laura, tableau d’après nature (2016) and his exegetical essay on Joyce, Ulysses, A reader’s guide (2010). He has been a co-founder of the Greek publishing house, Topos books.

You have published more than twenty books of fiction, literary critique and art. What drove you to writing and what continues to be your driving force? Would you say there are recurrent points of reference in your books?

Art in general and the art of writing more specifically has been my principal working method to handle, since my early twenties, the fast evolving world around me while, in my years of maturity, it has worked as a reliable instrument for me to perceive the complex impulses of a post-modern society in which inequalities, discriminations and agnostic hate stubbornly seem to persist. The art of writing real literature –not simply bedtime stories– demands oneself to plunge deeply into the history, the mythologies, the memories, the mentality and the dreams of people who, in times of crisis, tend to forget humanity’s best legacy, humanism, and consent even to the most hideous barbarity, e.g. fascism. These old themes, time and again, are easily traced in almost every book of mine, be it fiction or literary critique. Writing, in short, always has encouraged me to read and re-read our world, our societies, our ways of thinking everyday life.

In 2020, there were published two books of yours: a novel titled Φλλσστ, φλλσστ, φλλλσσστ and Πορτρέτο του Συγγραφέα ως Κριτικού, a collection of your literary reviews. Would you like to tell us a few things about both your ventures?

This recent novel is an attempt to portray the reactions of people who experienced the humanitarian crisis in contemporary Greece not just as a financial disaster, but, and this is equally important, as an ethical and even as a cultural threat to their lives. The story is told from the standpoint of a few old people (winter swimmers all of them) who choose to bypass the harsh events of the crisis that are raging around during the years 2012-2016 (reference is made indirectly to the most important events of the period) by striving to lead a somewhat secluded, secure life. But the events prove to be more powerful than these people’s subterfuge and invade violently into their petty lives so that the most valuable things they have loved, adored, believed and lived thus far become tested to death.

In short Fllst, fllsst, flllssst explores the limits of tolerance of a raped society – a society unprepared to fight not only against the economic sanctions suddenly put on it, but most importantly against the false credos permeating for decades, since WWII, its whole existence. The strange title refers to the incessant plashing of water at the edge of the sea. In the book this onomatopoeia emphasizes, reveals or simply accompanies every small or big turn in the lives of the main heroes. It is a constant reminder of Time, of the eternity of things, of the continuity of life against all odds.

The Portrait of the Writer as a literary Critic, is an anthology of literary reviews, essays and theses on culture selected out of a larger corpus of forty years literary work published in national newspapers, magazines or delivered as public lectures on various occasions. My starting point is the belief that the dominant literary critique in Greece has not succeeded to read the most important of its authors through a bold critical eye. It has preferred instead to hoard them indiscriminately and indifferently at the “museum” of national literary pride. For example, the legacy of the pro-modernist writers (end of 19th, beginnings of 20th century), like Viziinos, Papadiamantis, Roides, Mitsakis, to mention only the greatest of them –who are less known outside the narrow limits of the Greek speaking world, yet they are comparable to the great European masters of the same period– undoubtly deserves to be read and critically reviewed in the same demanding framework as that of Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Stéphane Mallarmé, Anton Tchekov etc. These writers, to say the least, represent an original example of modernism in a period when the first relevant experiments were just taking place in other parts of Europe.

So, that is one thing this book achieves: it re-maps the critical reading of the Greek literary tradition in the perspective of the European literary canon. By doing so it also achieves something equally important: since the mainstream critique has thus far limited its readings to the plot, the story, the period, the history of literature, its reviews have always remained tragically subjective, chauvinist, peripheral, stubbornly underestimating the originality of the above narratives. Well, my essays of these forty years constitute an attempt to re-read these original texts with a fresh eye without the myopic lenses of historism and critical impressionism, thus constituting an exemple of “scientific” critique. In the same book are also included a number of theoretical essays examining various cultural phenomena that have shaped / influenced dramatically the mentality of the post war generations of Greek people.

Your studies on James Joyce have significantly contributed to the understanding of Joyce’s work in Greece. How challenging was for you to delve into the work of one of the most important writers of the 20th century?

I have grown up with James Joyce. I started reading Ulysses when a freshman at the Athens University and have never stopped since then. James Joyce has been throughout all these years my primary, my college and my academic tutor. I have studied the best of European literature through my readings of his books. I have started reading Dante and Laurence Sterne at a period when both these texts were not yet properly translated into Greek. His books have been my royal road to continuously exploring the limits of knowledge, of language, of ethics, of ideas, of dreams, of writing – the road to discover not only who I am, but what person I wanted to be. His work, at a very early stage in my writing life, was the spark to experiment with the Word in all possible ways, to risk fearlessly into the unknown, to create with a single purpose: understand and enjoy in words what most people are afraid to understand and enjoy. So, the joycean adventure for me has been, and still is, an enduring education of self fulfillment, of self knowledge according to the socratic advice “γνώθι σ’ αυτόν” (= know thyself), and in so doing, a bliss without end.

You have characterized the body of literature as “an independent and almost libertarian democracy”. Could you elaborate on that?

I believe that the right to read and write, the right to incorporate oneself into the world legacy of texts and scriptures and writings constitutes a vital element of every civilized, democratic society. Excluding people from this right is as disturbing as exluding them from their essential rights to food, education, freedom, equality. In this context I believe that in a really free society everybody has the right to read and write whatever he desires; unrestrained, unchained of any ideological or other bonds. Moreover the fact that literature is by definition a universal symbolic place where everybody can meet and argue on any topic, where everybody can love and hate anyone, think and rethink his own life through the life of others etc., makes it a perfect model for the world where well known libertarians as Jean Jacques Rousseau and Denis Diderot aspired to live in – to say nothing of millions of people who are still having the same desire.

How does literature converses with the world it inhabits? Which role is literature called to play especially in times of multi-faceted crisis?

Literature has always been the child of the society which has given birth to it, a concave mirror reflecting both the good and the bad, the right and the wrong, the beauties and the monsters of its time. It is important for the writer to listen and engage himself in the demands of his society; but it is left to the reader to decide, to choose, to reflect on the literary donations of his time.

Literature is not a managerial mechanism of changing life into something more convenient, less burdensome. Literature has no power to improve one’s standard of life, one’s salary, one’s environment. Yet, literature can make one dream of (and demand) a better living, a better environment. History teaches that such kind of literary dreams can be very influential, especially in times of crisis. Diderot’s literature for example urged many people of his time to dream of a more human society and thus indirectly played its small role to the 1789 french revolution. Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s literature inspired a lot of young people in his country who demanded a society free of tsarism and thus indirectly played its role to the 1917 russian revolution. A convincing letter by the french novelist Emile Zola in a newspaper (his famous “J’ accuse”) was enough to sparkle a whole re-examination of the facts that had led to the imprisonement and disgrace of an innocent man Alfred Dreyfus, making a whole society to rethink its petrified beliefs.

A writer, a publisher, a translator, an editor, a literary critic. What is that binds all these different attributes together? Would you say that writing and literary critique constitute communicating vessels?

I consider myself a lucky man. I have always been engaged one way or another in the book production. I believe firmly in the power of reading, the power of good literature. In my life I have had the opportunity to translate books that I loved, to review books I loved, to publish books I loved. A lucky man indeed! The renaissance idea of homo universalis, has been my ideal throughout my whole life. In that respect, being a passionate reader had always meant to me that I should endeavour to cover practically everything area in the written universe. I have done just that. (Whether I have been successful or not it is for others to decide).

Literary writing and literary critique constitute two streams pouring into the same river of creation. I can’t conceive the one separately from the other. Most writers, most important writers, have followed the same creative path. The history of world literature provides indeed a convincing number of such examples.

Criticising in depth the creative ways of others, makes you a better connoisseur of yourself, makes you less arrogant, more self-conscious of your creative possibilities. Criticising the cultural habits / ideas / actions of people, makes you a better judge of your society, a more conscious citizen, a tolerant reader of the character of others. But then, all this critical work is the valuable equipment a writer needs in order to compose a decent text; and this explains how writing and literary critique communicate mutually in the creative act.

“Art doesn’t just constitute a product, among other products. It takes time, it requires an active participation. It demands time to be absorbed during which you have to work with yourself, to reflect upon yourself”. Tell us more.

The work of art, literary or other, though it is sold / bought in the market as all other products, should not be considered an ordinary consumer good. One can consume as many yoghurts as he likes in one day, week, month. But he can not do the same with the works of art, unless of course these products contain no other meaning for him except that of consuming.

The work of art is consumed, so to say, in the long run. The real work of art is to its consumer a lifelong relationship and as it happens to all relationships in real life it deploys in front of him an intimate story of skin and blood, of laugh and joy, of wrinkles and sorrow, of discovered secrets, of ties in love and hate, of tragic and happy moments etc. In real life relationships of this kind are never consumed one after the other, “one-night stands” are no real art consumer’s favorite cup of tea.

As we are selective with our friends in life so we should be selective with our literary / art friends. It takes time to become a real friend with someone or even to dismiss him, it takes time to understand and feel in depth new people, new books, new works of art. It takes time to understand one’s choices, one’s preferences in life and the same applies to art consuming.

Both the recent socio-economic crisis and the current health pandemic have adversely affected the Greek book market and publishing houses in this respect? What are the prospects ahead for books?

The book market in Greece is addressed to a limited number of approximately 15.000 active readers, people, that is, for whom the book is vital to their life. Both the economic and pandemic crisis have been a heavy blow for book buyers, mainly because the readers I have just mentioned are, in their majority, of low and middle class incomes.

As for the prospects for the book industry in Greece the real answer to the problem lies in public libraries. In this country lending public libraries do not respond as they should to these extraordinary circumstances. They must here and now get modernized. We need better organized municipal and public libraries as well as better organized school libraries. There is an urgent need for a central organization of all public libraries obeying to a firm, central state policy supporting readership; with an alternating animation programme that will urge people to read more; with a brave school programme that will convince young people (whose reading is limited to their mobile screen) understand the necessity of reading books for their future.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE