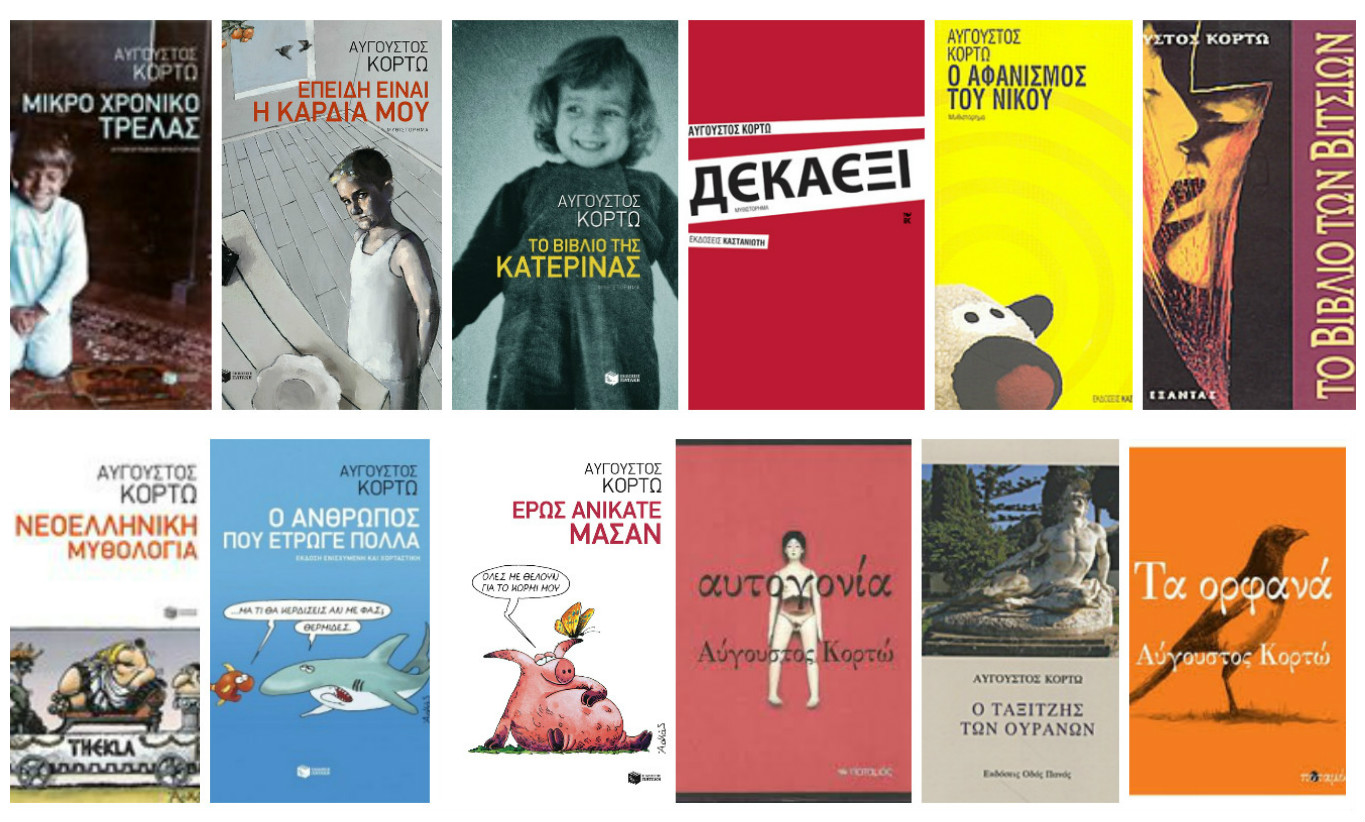

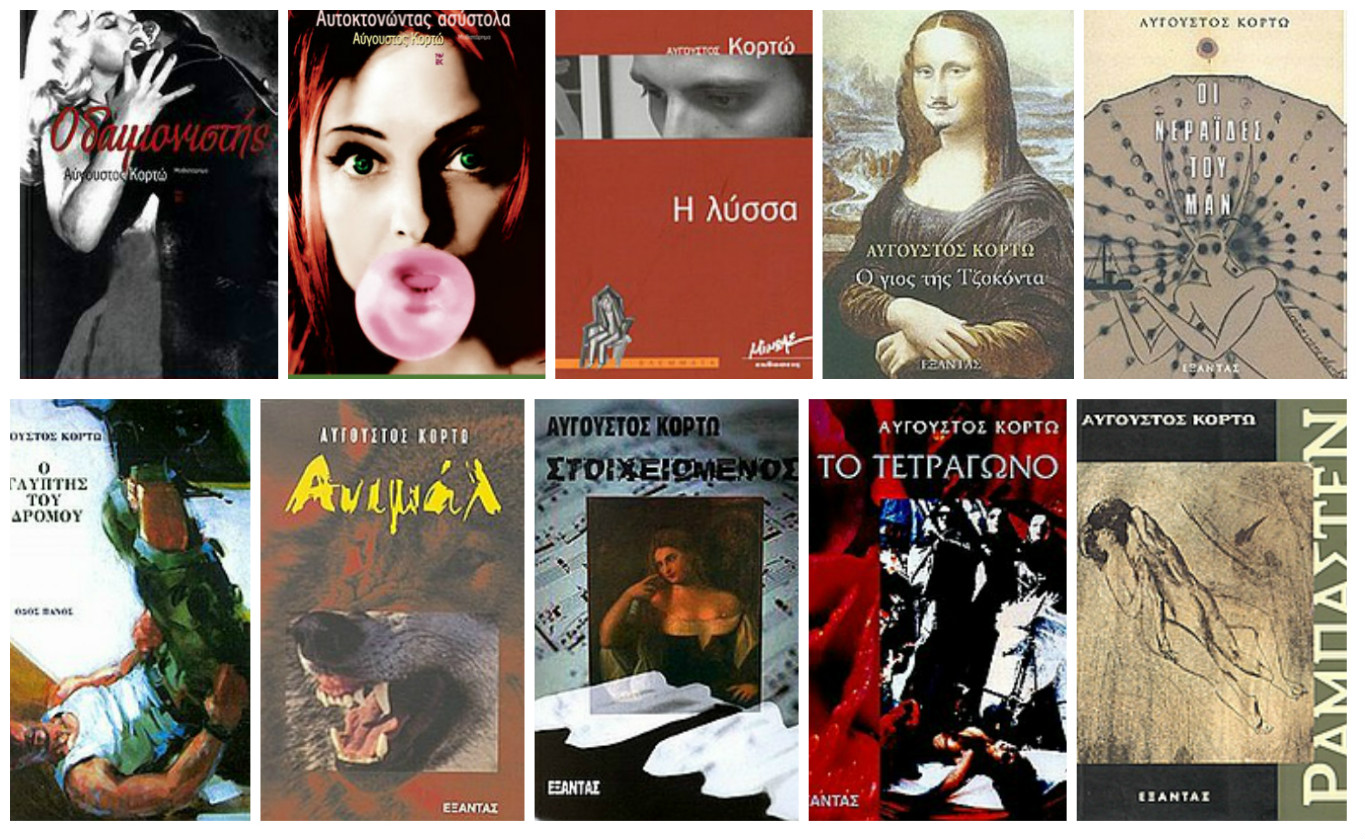

Auguste Corteau (1979) is a fiction writer, a playwright and a translator. He has written novels/novellas: Rabastin (1999), The Square (2000), Haunted (2001), Animal (2002), The Streets Sculptor (2002), The Man Faeries (2003), La Gioconda’s Son (2003), The Rabies (2004), Shameless Suicides (2005), The Demonizer (2007), The Obliteration of Nicos (2008), Sixteen (2010), The Book of Katherine (2013), Because It Is My Heart (2014), short story collections: The Book of Vice (1999), plays: The Orphans (2012), Suigeneris (2014), comic shorts: The Man Who Ate Too Much (2012), Love Me Tenderloin (2015), Ancient Greek Myths Revisited (2016) poems: The Cab Driver of Heaven (2012), a memoir: A Memoir of Madness (2016) and an original script for the movie Testosterone by George Panoussoupoulos, 2004).

He also won the 2004 Greek National Book Award for Children’s Literature and the IBBY Prize for Best Children’s Novel. He has also worked extensively as a translator, and has translated into Greek numerous works by English-language writers, amongst them books by Nabokov, Banville, Updike, Annie Proulx and Cormac McCarthy.

Auguste Corteau spoke to Reading Greece* about what changed and what remained the same in his writings all these years noting that “I was a mostly unhappy adolescent when I wrote my first short stories, while now I’m a happily partnered man”. He comments on his writing obsessions, he explains why he first writes in English and characterizes himself as a “musician manqué”.

As for his translation works, he notes that “I feel immensely responsible – accountable – when translating a book […] So I don’t allow myself the slightest haste or sloppiness”. He concludes that “one can still infer a much deeper understanding of another human being from the way they express themselves in writing. That is why the necessity for writing in these troubled times can only proliferate”.

From The Book of Vice in 1999 to A Memoir of Madness in 2016. What has changed and what remained the same?

I was a mostly unhappy adolescent when I wrote my first short stories, while now I’m a happily partnered man. All the books I read between these two points in time, all the people I met and was blessed with being loved by, have molded me into a quite different writer than the one I was back then. And for this I am profoundly grateful.

“You cannot escape from your writing obsessions, from what fills your everyday life: love, fear, death, anger”. What drove you to writing? And what continues to be your driving force?

The stories I consumed – the books I still devour – they are to blame: too many realities colliding within me. At some point, a new one – my own invented world – had to emerge. (By this I don’t mean to downplay the role of experience, of personal drama; however, all drama is humdrum when compared to what the human mind can conjure all on its own).

What about your love for music? How is it imprinted on you writings?

I am a musician manqué. To this day I hold no human creation holier than music.

“I feel that the English language is the ideal language for writing prose: playful, malleable, with endless potential”. How is it that you first write in English and then you translate your writings in Greek?

I turned to English after my sole major case of writer’s block. For more than twenty years, my mother tongue is interchangeable with English – so I sort of slip from one to the other as easily and unthinkingly as one finishing a book and going on to read another book written in a different language.

As Karen Emmerich has eloquently put it, “the strongest ethical claim for translation is that it demands of us a willingness to inhabit an open book, to maintain a sense and an attitude of uncertainty, and to welcome the endless provisionality of our answering”. Where does the role of a writer meet that of a translator?

I feel immensely responsible – accountable – when translating a book, regardless of its subject and my personal feelings towards it. It is a work of literature whose sole Greek translation will, in all probability, be the one I deliver. So I don’t allow myself the slightest haste or sloppiness.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of Greek literature in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained? What about literature in the era of digital communication?

One can still infer a much deeper understanding of another human being from the way they express themselves in writing. That is why the necessity for writing in these troubled times can only proliferate.

Read: The Book of Katherine (an excerpt in English)

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE