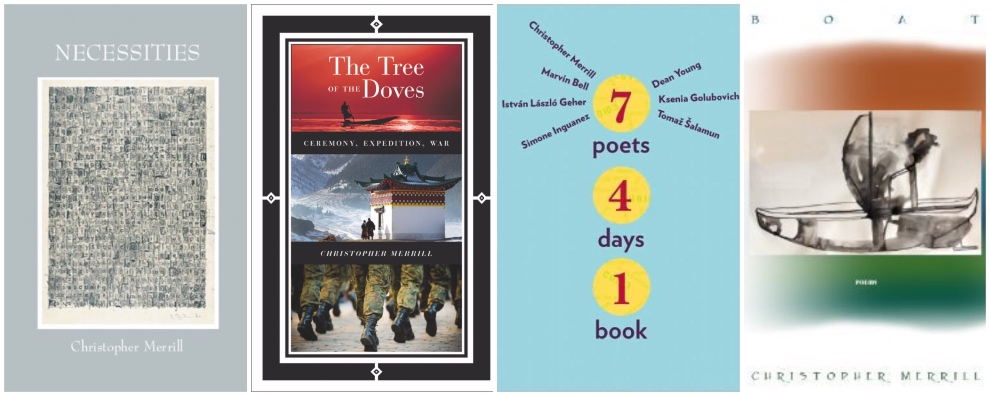

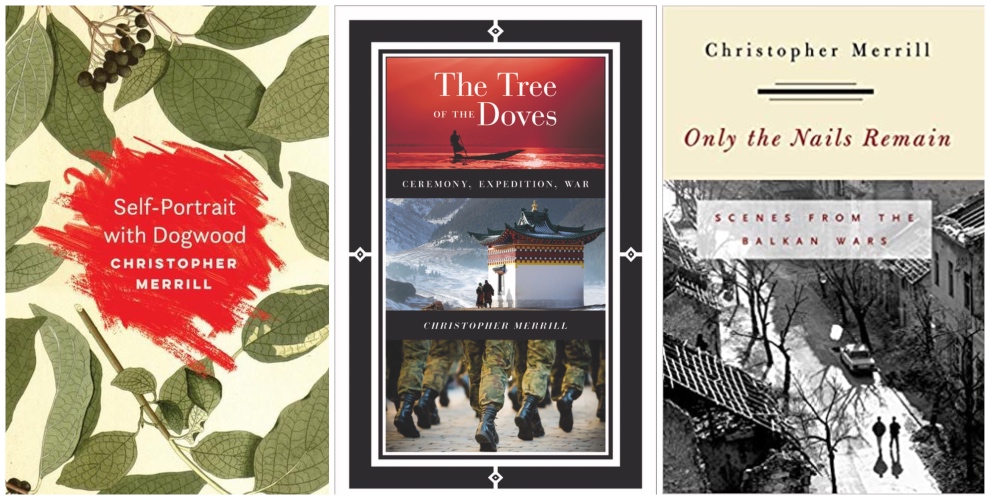

Christopher Merrill has published six collections of poetry, including Watch Fire, for which he received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets; many edited volumes and translations; and six books of nonfiction, among them, Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars, Things of the Hidden God: Journey to the Holy Mountain, The Tree of the Doves: Ceremony, Expedition, War, and Self-Portrait with Dogwood. His writings have been translated into nearly forty languages; his journalism appears widely; his honors include a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres from the French government, numerous translation awards, and fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Ingram Merrill Foundations. As director of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa since 2000, Merrill has conducted cultural diplomacy missions to more than fifty countries. He served on the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO from 2011-2018, and in April 2012 President Barack Obama appointed him to the National Council on the Humanities.

Christopher Merrill spoke to Reading Greece* about the various “strands of [his] literary identity” noting that “curiosity is what binds them together”, “a restless imagination determined to make sense of the countless mysteries integral to human existence”. Asked about what drove him to poetry, he mentions “the compression and precision of language, the musicality embodied in rhyme, meter, and the management of vowels and consonants, and the juxtaposition of imagery, surreal and realistic”. He adds that “reading poetry in translation shaped [his] practice as a poet” noting that “Edmund Keeley’s translations of Cavafy, Seferis, Elytis, and Ritsos were .. a window onto a world that has formed [his] thinking and practice as a poet in the most important ways”. As for the role cultural diplomacy plays in an increasingly globalized world, he comments that it is “a vehicle for bridging differences between the citizens of countries at odds with”, “an arena in which we agree to lay down our swords in order to speak from the heart”.

A poet, a translator, a journalist, a cultural envoy. Where do all these attributes meet? Is there a binding thread?

Curiosity is what binds together the separate strands of my literary identity. An image, a string of words, or a cadence can start a poem, engaging my imagination in a process of discovery, shaped at every turn by my desire to see what lies around the next bend in the road, and something similar occurs when I translate poetry, research and write articles, essays, and books, and embark upon cultural diplomacy missions. Human beings are meaning-making animals, and for the forty or so years that I have written seriously I have always sought to understand something essential about my time here below. The variety of literary projects I have undertaken may suggest an inability to focus on one genre or idea. But I prefer to think this reflects a restless imagination determined to make sense of the countless mysteries integral to human existence.

There is a passage in my book about Mount Athos, Things of the Hidden God: Journey to the Holy Mountain, that in my mind addresses the seeming incongruity of my work, which includes books on soccer, war, Orthodox monasticism, Georgia O’Keeffe, nature writing, and travels in Asia and the Levant:

It was a strange feeling. I kept thinking I had strayed off the trail, but whenever I looked behind me the way was clear. Under overcast skies I was hiking north along a cliff, in heather and sage, cypresses and chestnut trees, relying on my instincts to navigate through the confusing terrain. The system of footpaths was overgrown in several spots, because most pilgrims preferred the taxi to walking from monastery to monastery. Descending from a cliff to a cove buffeted by a stiff wind, I came to a rocky beach where the path vanished under mounds of sea wrack, oil cans, and plastic containers. There was even the hull of a boat washed up on shore. The seaward rocks were covered with a mustard-colored lichen, and in the next cove a dog was barking in a stone tower overlooking the surf; the wooden bridge above the rocks swayed in the wind, and several steps were missing from the staircase to the third-story entrance. The shrine at the far end of the cove looked like a better destination, but when I reached the brick-and-stone hut I could not read the sign, in Greek, on its lintel. I turned around and saw that I was still on the trail.

Which is to say: I may be walking blindly into the future, following one uncertain or unreliable path after another, but I hope that in the end it all adds up.

You have published six books of poetry so far. What drove you to poetry and what remains your driving force? Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

The compression and precision of language, the musicality embodied in rhyme, meter, and the management of vowels and consonants, and the juxtaposition of imagery, surreal and realistic—these were the elements of poetry that first attracted my attention, along with the simple fact that poems spoke to me more directly than any other art form. And this is still the case: a day without reading or writing poetry is for me a lost day.

Love and loss are enduring themes, along with the play of the imagination, nature, faith, and the political realities of living in a country that seems bent on self-destruction. I grieve daily over the accumulating evidence that our grand experiment in liberty is coming to an end. Sometimes that grief turns into poetry.

Would you say that your identity as a poet has been influenced by the translations of foreign poetry you have undertaken?

Let me begin by observing that reading poetry in translation shaped my practice as a poet before I learned to translate. To take the most relevant example: Edmund Keeley’s translations of Cavafy, Seferis, Elytis, and Ritsos were not only my introduction to the glories of contemporary Greek poetry but a window onto a world that has informed my thinking and practice as a poet in the most important ways. A seminar with Joseph Brodsky at Columbia University in 1980 was decisive: we read Cavafy, Czeslaw Milosz, and Zbigniew Herbert—three poets who helped me to develop what W. H. Auden called “a code of conscience.” My studies in Old English, during which I translated one hundred lines of Beowulf every day, and the discovery in a used book store of Michael Benedikt’s anthology of French Surrealist poetry opened new routes to the interior, which I followed as a poet and translator, bringing into English André Breton’s last book, Constellations, which inspired my book of prose poetry, Necessities, and then a book that Breton wrote with Paul Éluard and René Char, Slow Down Construction, which two decades later led me to devise the collaborative 7 Poets 4 Days 1 Book. My translation of Aleš Debeljak’s Anxious Moments influenced my new book of prose poems, Flare, as well as my ongoing collaboration with Marvin Bell, After the Fact: Scripts & Postscripts. Translation offers me the chance to hear poems approaching in different frequencies.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie?

Poetic form and content are inextricably intertwined in every language that I know of. The translator’s twin responsibilities are thus to be faithful to the original and to create a lively version of the text in the target language. This is, of course, impossible—and yet translators persist in finding approximations that delight readers and invigorate the local literature. We call politics the art of the possible. The same holds for translation.

“If I had learned anything about the war, it was that our walk in the sun is brief, and so I resolved to wander from monastery to monastery, a sojourner in the world of last things.” What’s the story behind your gripping account of the pilgrimages you made to Mount Athos in Greece in the aftermath of the Balkan wars in the 1990s?

I traveled from Skopje to Thessaloniki during the war to get cash—the sanctions imposed by the UN prevented the use of credit cards in the former Yugoslavia—and there I had the good luck to dine one evening with a local journalist, who served a delicious red wine made on Mount Athos. He described some of his experiences on the Holy Mountain, which gave me the idea of making a pilgrimage—an idea that acquired greater urgency when I left the war zone that spring to housesit on the Hawai’ian island of Maui for the poet W. S. Merwin. Writing and reading in Merwin’s botanical preserve, where he had planted thousands of palms that were either endangered or extinct in the wild, was a balm for my soul after what I had experienced in the Balkans. One day I read his lengthy essay about Mount Athos, which is devoted more to the natural history of the peninsula than to a meditation on spiritual matters or last things, and this prompted me to consider concluding the book I was writing about the former Yugoslavia—Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars—with a visit to the Holy Mountain—an idea that wound up on the cutting room floor. My book ends on the day of the first municipal elections after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords. But I could not stop thinking about Mount Athos. I had reached a crossroads in my own life, the war having taken a physical and spiritual toll on me, and when I got the chance to make the first of seven pilgrimages to the Holy Mountain I began to write my way into a new view of my time on earth—a view that honors the ancient practices, artistic glories, and of Eastern Orthodox monasticism

As director of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (IWP) since 2000, what were the main initiatives undertaken during your twenty-year tenure? What do you hope your legacy at the IWP will be?

My first task was to rebuild this storied program, which had fallen apart, thanks to my predecessor’s mismanagement. The university backed off its threat to place the IWP into receivership, the academic equivalent of bankruptcy, and hired me to set things right, which was no small task. Just as Americans are learning, tragically, that it does not take as much as we might imagine to destroy a grand experiment over which men and women of good will have labored for a long time, so I realized I would have to be ever vigilant in my efforts to reconstruct what was best about the IWP—the fall residency, which hosts distinguished poets and writers from around the world—and to develop new programs to match the changing tenor of the times: digital learning courses; summer writing programs for high school students from different countries; international conferences, including three sessions of The New Symposium on Paros; tours of American writers abroad; an online introduction to and commentaries on Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and his Civil War writings, translated into many languages, including Arabic, Farsi, Russian, and Spanish; a digital journal, 91st Meridian; and much more.

I hope my legacy will focus on the vitality of the programs I developed and the durability of the structures I put in place to secure the IWP’s future.

In an increasingly globalized world, what role does cultural diplomacy plays? What about your own experiences as a cultural envoy around the world?

Cultural diplomacy, traditionally defined as the exchange of information and ideas, generally in the form of people-to-people exchanges, is a vehicle for bridging differences between the citizens of countries at odds with . And on the cultural diplomacy missions I have undertaken to more than fifty countries I have seen how poets and writers on opposing sides of a political issue may nevertheless find common ground through honest dialogue. What artists in every medium share is the desire to make something new, which will not only speak to their particular moment but endure; what they may glean in conversations with their foreign counterparts about their and craft may be exactly what is needed in order to move forward. Cultural diplomacy is an arena in which we agree to lay down our swords in order to speak from the heart.

This was a lesson I learned in the Dadaab refugee camp, on the border between Kenya and Somalia, where I had traveled with three American writers to teach a series of creative writing workshops to students aged 18-30. Perhaps this excerpt from an essay I wrote about the virtues of cultural diplomacy will explain why I do this kind of work:

Morning and afternoon, we would drive from the UNHCR compound to the police station in Dadaab and wait for the Kenyan policemen to escort us to the camps. They’re probably drinking tea, the press officer would say, shaking his head. They’ll come when they feel like it. The policemen accompanied us after the last workshop in Ifo to N-0, the newest camp, where the latrines placed between two rows of tents were used by forty people. Thorn branches served as gates to each tent, some of which housed as many as twenty people. Three students joined us, one of whom had opened the question-and-answer session earlier in the morning at the community center by saying that since he was giving up his time to study for exams he wanted to know what was in it for him. We had praised the pleasures of aesthetic exploration, but I had the feeling that we had not convinced him or his friends that this would be time well spent. But here they were, now translating for a wizened man who recited a poem about businessmen in Somalia sending their families out of the country and doing nothing for refugees, now helping us to wade through the crowd that swarmed around us. An old man harassed me for failing to visit sooner, and after he had said his piece he shook my hand in the traditional way, and led me on a tour of the camp. A woman surrounded by children took up the theme of his tirade, saying that at the hospital she could not get any medicine. What are you going to do for us? she demanded to know. I said that I could write about what I had seen—and then one of the students said that he and his friends could write about this, too. That’s right, I said, brightening. I’ve been here three days, you’ve been here years. You know this story better than I will ever know it.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Ram Devineri

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE