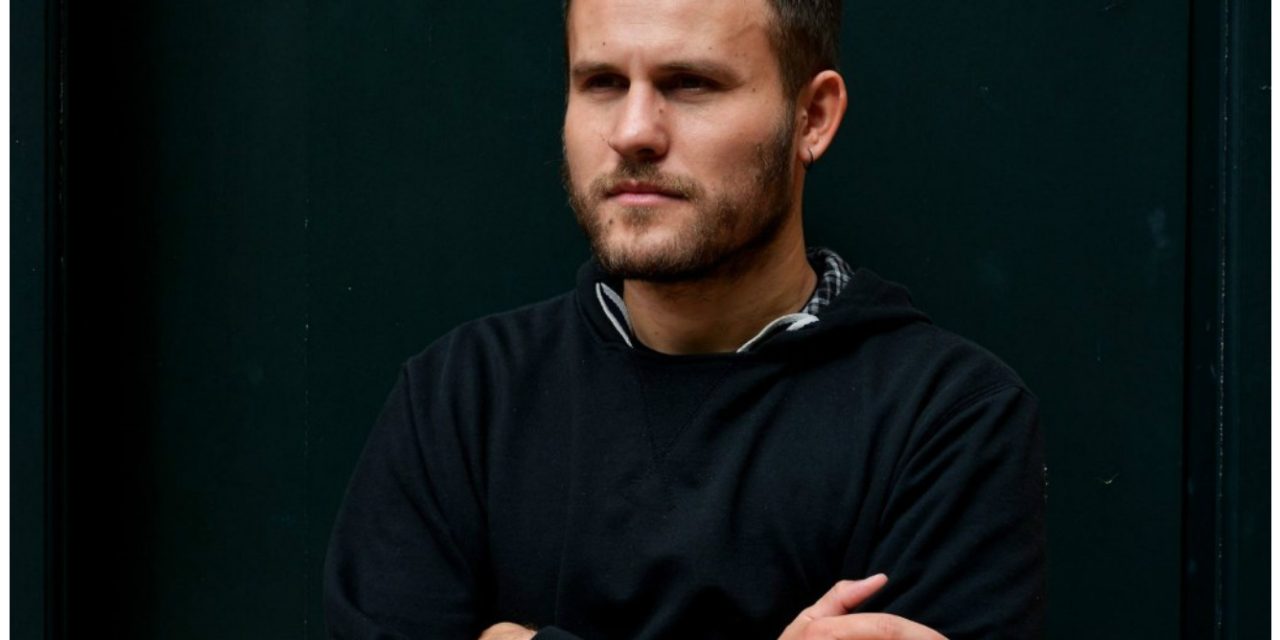

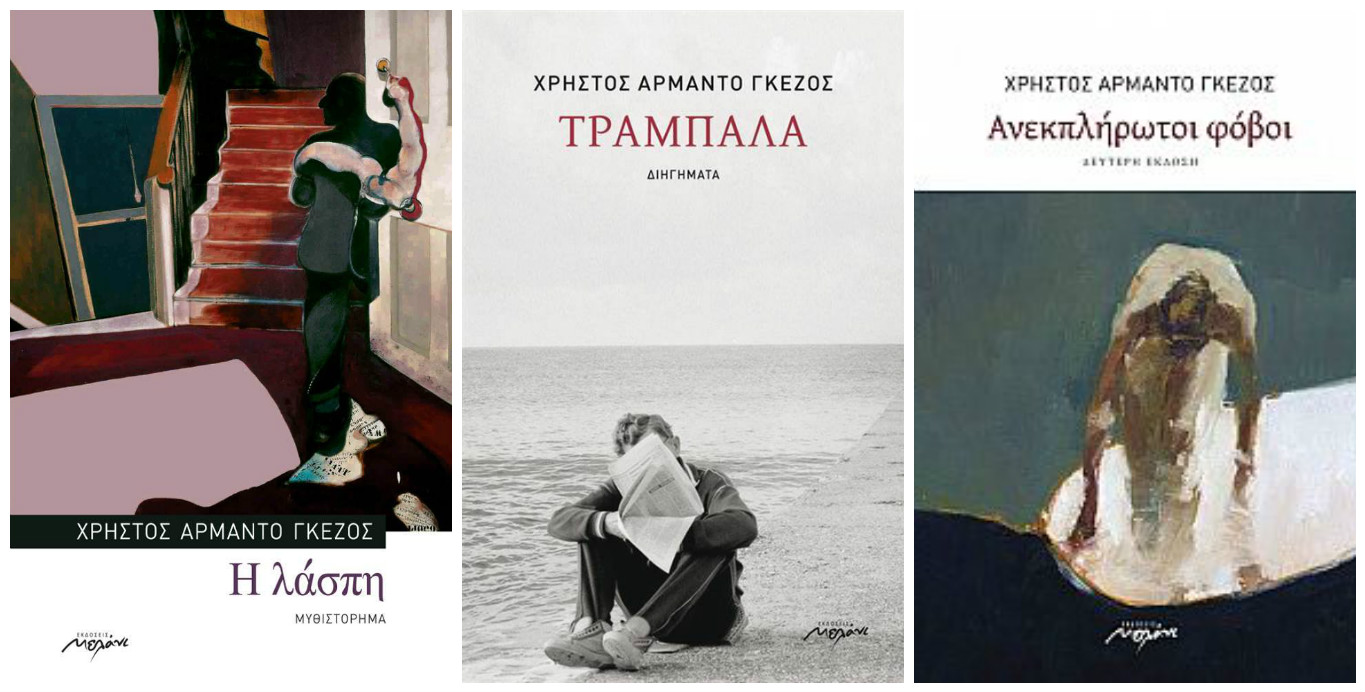

Christos Armando Gezos (1988) is an author and a poet. In 2012 he published his first poetry collection titled Ανεκπλήρωτοι φόβοι [Unrealized Fears] for which he received the State Literary Award for Debuting Author in 2013. His first novel Η λάσπη [The mud] was in the short list of the Athens Prize for Literature for the Best Greek Novel of 2014. His third book, a short story collection titled Τραμπάλα [Seesaw] was published in 2016 by Melani Publications.

Christos Armando Gezos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book, which forms the third part of an informal trilogy aiming to depict life as it really is: “a pendulum that moves from pain to hope, from life to death, from boredom to despair, from tears to laughter”. He explains that his personal experiences are usually the starting point of his writing, noting that the flexibility of language in its many incarnations has allowed him to depict the many different micro-realities that exist.

He describes poetry as “an extract of sadness, a refined melancholy flowing thick and hot through the cracks that open up in moments of deep intensity”, while he characterizes prose as “a more cerebral pursuit allowing your feet to plunge into waters of many different hues and temperatures”. He explains how estrangement in its various forms is imprinted on his work, while he comments on the main challenges that lie ahead for literature concluding that “it is important to assimilate the historical developments that are changing the world, whilst not denying their timelessness”.

Your first short story collection, Τραμπάλα, was recently published. Tell us a few things about the book.

Τραμπάλα, which consists of 10 short stories, is my third book, following a poetry collection titled Ανεκπλήρωτοι Φόβοι [Unrealized Fears] (2012) and a short novel H λάσπη [The Mud]. Τραμπάλα essentially completes an informal trilogy focusing on a common attitude towards life and reality: an overwhelming fear fueled by the certainty of death and, more importantly, by all the things that may precede death; the desperate awe man feels standing helpless against the world and himself. What I wanted to achieve specifically with Τραμπάλα is a more balanced representation, to depict life as I think it really is: a never-ending spectrum of emotions and situations, a pendulum that moves from pain to hope, from life to death, from boredom to despair, from tears to laughter.

My heroes are often obsessive, led to extremes either because of their inherent sense of self-destruction or as a result of the restrictions imposed on them by nature and society. Ambivalent, bitter, fully aware of the difficulties of the world, conscious of the wounds that have formed them so far, with a painfully acquired maturity that allows them to make the next step, no matter how uncertain and shaky it may be.

The Mud is a novel about a man who tries to define himself in relation to the world against all odds, both real and imaginary. Do you identify with your heroes? To what extent is your writing experiential?

Whilst my personal experiences are usually the starting point of my writing, I don’t want them to be the endpoint, so as not to restrict the scope of the text. What I want to do is to use my own experiences as elementary components of human experience everywhere, so as to write stories that other people may also relate to.

I have some dark sides which I choose to illuminate from certain angles and with a particular intensity, sometimes with neon red and others with electric blue. To build the body of the text I sometimes have to cut parts of my own body, some of which I glue together as they are, and others I work on like clay to give them a new shape. In the end, I may end up either with a flower or a Frankenstein.

Both your language and the techniques you employ (e.g. lack of paragraphs and full stops) is quite daring. Is this a conscious decision on your part?

For me language is not an end in itself; rather, it is determined by the story you want to narrate. In The Mud I opted for long sentences and a scarcity of punctuation in an effort to depict the protagonist’s troubled psyche and suffocating emotions. The same goes for some of my short stories where I wanted to leave a similar imprint. Yet, in others, narration is more sober and down-to-earth. There are so many stories, so many micro-realities for you to create, so many people that think differently, live differently, suffer differently, love and die differently. That’s why the flexibility of language in its various incarnations is so valuable and admirable.

Your writing seems to walk the line between prose and poetry. What does each form of writing constitute you? Where do you draw your inspiration from?

For me poetry is more like an extract of sadness, a refined melancholy flowing thick and hot through the cracks that open up in moments of deep intensity. Prose is a more cerebral pursuit allowing your feet to plunge into waters of many different hues and temperatures.

Octavio Paz has described poetry as a death leap that breaks the boundaries of existence and takes us to the other side; in other words, poetry digs deeper and so it’s easier to discover the truth, albeit in forms that work more on an emotional level. Prose – through narration, plot, characters and time spread – constructs a more tangible reality, while it dissipates and dilutes pain, thus giving the writer greater freedom of intellectual and linguistic expression.

As for inspiration, it can literally come from everywhere. A scene on the street, a memory, a random flash through the mind, a song, a poem, a movie, a news item on the internet, words uttered by a passerby.

“I feel privileged that being ‘rootless’ gives me the chance to mentally travel in various places and take advantage of what I write”. How are the notions of ‘homeland’ and ‘roots’ imprinted on your work?

A lot of the poems in Unrealized Fears refer to estrangement both at social and interpersonal level, and as I realized later on following comments by readers and critics, they were (or could be) the imprint of unconscious concerns about my national identity. This was an issue which I then felt didn’t bother me but, along the way, in The Mud, it became more evident, but again it remained in the background, more like a footnote to the hero’s existential reflection while swaying between two homelands. And this is the way I want it to appear in my texts, outside the restrictions imposed by the quest within a framework of national self-determination: in a way that will reflect the fluidity and staggering of all people, their relentless march forward, all of them similar to each other but simultaneously and inevitably strangers.

In a recent interview, you have noted that “we are going through a period that all arts are faced with an unprecedented disillusionment”. What are the main challenges that art and, more specifically literature, are confronted with nowadays?

I guess the major challenge literature is faced with nowadays is adjustment to the completely different landscape that the digital era has introduced. There are many consequences, positive and negative, both in terms of theory and practice. The internet and smartphones have influenced current reading patterns, the time devoted to reading and memorizing abilities. Social media have familiarized unsystematic readers with written language, while they have expanded the boundaries of what we have come to understand as literature. It is no coincidence that on the occasion of Bob Dylan being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, many people wondered whether we’ll see the prize being awarded to a blogger or someone who posts on Facebook.

In any case, I believe that in the long run the balance will be positive: everyone will be able to read whatever they want from the comfort of their house, even free of charge, download masterpieces and listen to great music. It’s a diffusion of culture into daily life. As for artists, the major challenge is how to avoid crude and non-creative repetition (not in the sense of saying something new, which is not possible, nor is it the issue), which becomes more difficult given the accumulation of intellectual production over the centuries. It is equally important to assimilate the historical developments that are changing the world, whilst not denying their timelessness.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read also: Interview of Christos Armando Gezos to Grèece Hebdo (in French)

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE