Clara Villain is a translator of modern and contemporary Greek and Cypriot literature. She studied Modern Greek in Paris (INALCO – Institut National des Langues et Cultures Orientales) and literary translation in Athens (Professional Training Program for Young Translators of Greek Literature – Kostas & Eleni Ouranis Foundation and Charis Petrou Foundation) and Paris (École de Traduction Littéraire – CNL/Asfored). In 2021, she was shortlisted for the “Prix de la traduction VoVf – INALCO” translation award for the translation of the novel Dendrites (Sillages) by Kallia Papadaki.

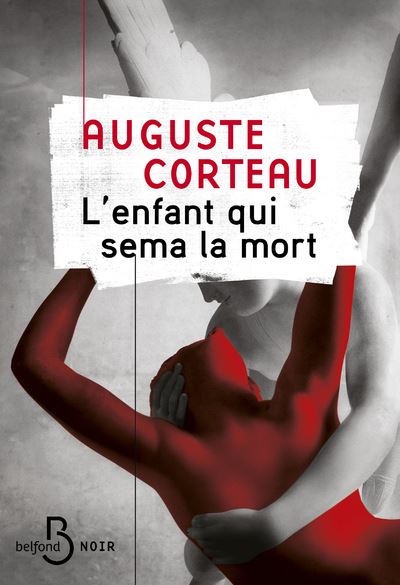

Your latest translation venture L’enfant qui sema la mort by Auguste Corteau was recently published into French (Belfond, 2024). Tell us a few things about the experience.

Translating a novel like L’enfant qui sema la mort (Μισό παιδί) by Auguste Corteau, which deals with some very sensitive topics such as women and child abuse, xenophobia, LGBTphobia and weapons ownership, can be quite draining emotionally and I dreaded the moment I’d have to dive into some of the darkest passages of the book. To my surprise, the pleasure I found in the quality of the prose outweighed the stress caused by the depicted violence. Actually, despite the gravity of the matter, Corteau’s writing is filled with both humour and tenderness.

Professionally speaking, translating Corteau’s novel has been a pleasure from start to finish. I wish all translators to experience working under such favourable conditions. Communication has been kind and efficient with all parts involved, from the agent Katerina Fragou and the author himself to the publisher and editor at Belfond publishing house.

What made this translation so special for me also lies in the fact that Auguste Corteau not only has a strong knowledge of French language but happens to be a seasoned translator and could therefore assess by himself the quality of my rendition. It would be lying to say this awareness didn’t come with a bit of extra pressure. I was really glad —and relieved — when he told me how much he appreciated my work.

I sincerely hope this novel will manage to reach many French-speaking readers and receive the warm welcome it deserves.

How did your involvement with Greek literature begin? Which are the main challenges you have faced while translating Greek literature into French?

Although I am of no Greek descent, my special bond with Greece clearly originates in the story of my father, who traveled to Peloponnese in his early twenties and spent nearly a year there in a small village, working with locals in farms and olive fields. The Colonels dictatorship forced him out of the country and even if he didn’t get to visit his ‘second home’ for more than forty years, he kept a strong connexion to its language, poetry and music. The Greek songs he would sing for us when I was a child and the dictionaries almost permanently laying on his desk definitely made a strong impression on me.

Because I’ve been homeschooled for years, I had the opportunity to start learning modern Greek at the age of fifteen and benefited from the excellent educational content of the French National Center for Distance Learning (CNED) as a part of my high-school curriculum. After almost a year of learning the language, I finally went to Greece for the first time. At the end of the third year, I remember traveling to Paris to take the final examination — an oral analysis of My Grandmother Athens by Kostas Tachtsis. I was the only student without any Greek roots, most candidates were actually native speakers all up for some easy extra points. Having graduated from high school, I then dedicated seven years to studying music before finding back my way to modern Greek. In 2015, I earned a bachelor’s degree in Modern Greek Studies in Paris.

My acquaintance with Greek music and poetry also owes much to the late Angelique Ionatos and to Katerina Fotinaki, two wonderful singers-songwriters and close friends of mine, that I had the privilege to work with for a while. They introduced me to the work of some major poets, such as O. Elytis, N. Gatsos, K. Karyotakis and K. Palamas.

In 2017, determined to try living in Greece despite a complex economic situation, I was working in a call center in Athens forty hours a week and bored to death when I decided to apply for the Education and Vocational Training Program for Young Modern Greek Literature Translators (Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation – Haris Petrou Foundation). Being able to join this program, which unfortunately doesn’t exist anymore, not only gifted me some of my most precious friends, but has also been a real turning point in my journey as a translator. I was working under the supervision of Lucile Arnoux-Farnoux, translator and professor of comparative literature at the University of Tours, specializing in the study of Modern Greece, and I cannot stress enough how much I value the guidance I received from her.

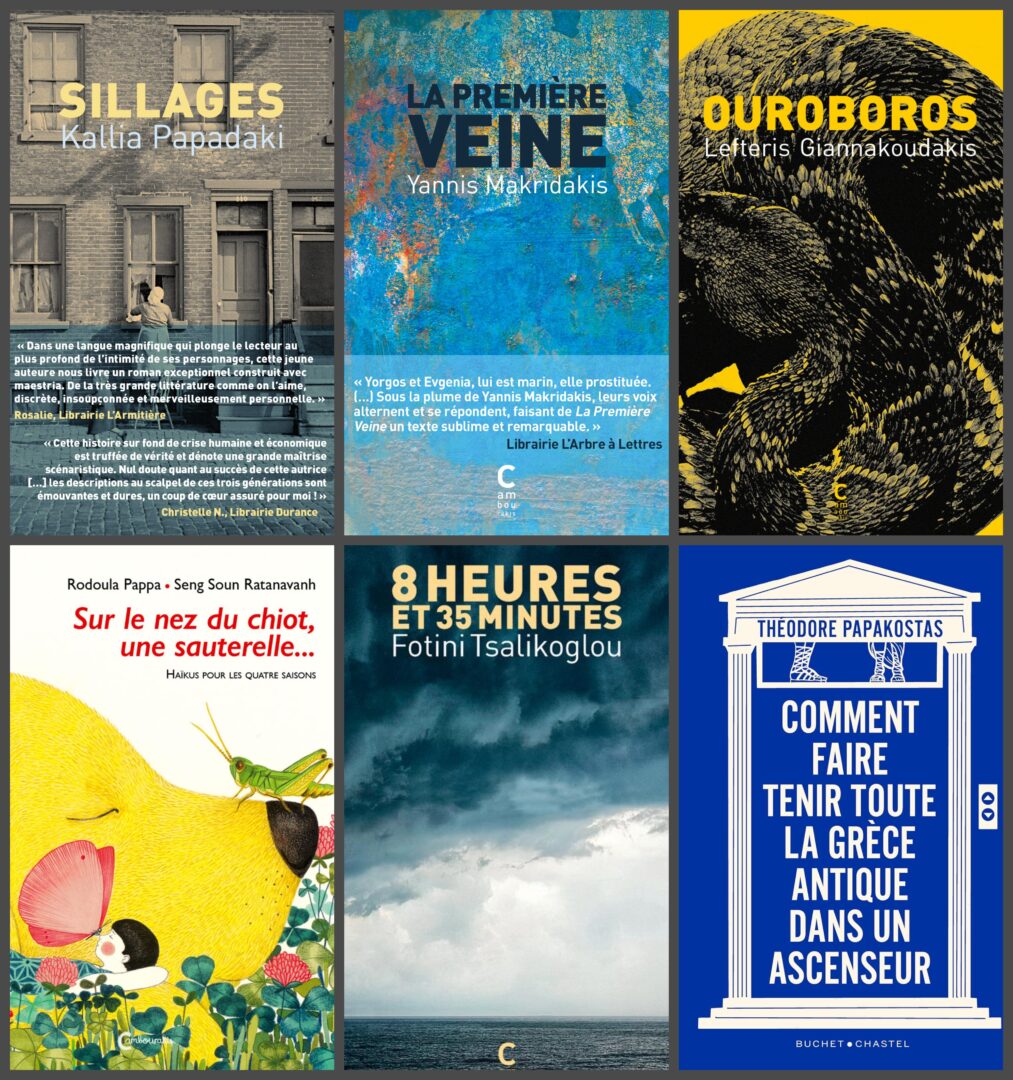

My very first published translation was completed in the frame of this training: Kallia Papadaki’s novel Dendrites (the winner of the 2017 European Union Prize for Literature) was a highly challenging text to start with, mainly because of the length of the sentences — many of them exceeding a full page —, but it remains to this day one of the most interesting books I have worked on. My translation was published by Cambourakis, Paris, and shortlisted for the « VoVf – INALCO translation award » in 2021. Since then, I have translated novels, shorts stories and children books by authors such as Yiannis Makridakis, Auguste Corteau, Fotini Tsalikoglou, Kallirroi Parousi, Christos Kythreotis and Lefteris Giannakoudakis, among others.

I always like to mention my collaboration with historians, scholars and institutions like the Benaki Museum or the École Française d’Athènes because they give me the opportunity to work on texts and articles I would otherwise never read. This non-literary part of my activity as a translator constitues a truly enriching experience and helps me to deepen my understanding of Greek and Cypriot history and society.

As for the challenges one faces when translating Greek literature into French, except from the difficulties inherent in the art of translation, I would say that the use of dialects by Greek authors sometimes feels like an insurmountable obstacle and implies strong decisions and creative solutions. Also, the multiple repetition of a word in a same page, paragraph or even sentence, that goes rather unnoticed in Greek, would often be seen as disturbing, heavy or clumsy by a French-speaking editor. A balance must then be found between sticking to these repetitions as being part of a writer’s style and producing a text that won’t discourage a French-speaking reader.

A variety of cultural elements (some vocabulary related to orthodoxy or some subtle references to the civil war, for instance) can also bring the translator in a difficult place: it sometimes requires extensive terminological or historical research and the result can be quite disappointing when the appropriate French term sounds way too technical or when a footnote proves necessary, bringing emphasis on what was nothing but a detail of limited importance in the original text.

Lately, I’m tempted to say that the main challenge we face actually lies in convincing publishers to invest money and time in a Greek book!

What is that makes Greek literature appealing to French readers? Does contemporary Greek literature have the potential to attract foreign audiences?

First of all, we shouldn’t forget that any French-speaking reader eager to discover Greek literature can access a frankly impressive amount of translated works, probably hundreds of them. Unfortunately, despite the fact that France has a long tradition of translating Greek writers, it seems like this rich heritage still struggles to reach a wider audience — with the exception of a few well-known authors such as Seferis, Kazantzakis or more recently Petros Markaris.

But I honestly don’t think this struggle is specific to Greek literature. The European culture market is thoroughly and increasingly dominated by English language, the supremacy of which also applies to cinema, music, video games, digital content, etc., leaving close to no space for « minor » languages and cultures to reach an international audience. Main streams getting stronger at the expense of diversity seems to be a global trend, observable in many aspects of our society.

As for Greek literature, quite some French publishers seem to dream of novels (not too short, not too long) that would be universal but still have a very strong « Greek colour », i.e. matching the image they think readers have of Greece — glorious past, blue sea and white chapels, social misery striking a middle-class devastated by the crisis.

Fortunately enough, some publishers are genuinely interested in discovering the diversity of Greek voices (and realities) and believe that the quality of the writing should be the first criteria when choosing to publish a book. The potential is definitely there and many good books, addressing a great variety of topics, are waiting out there to be spotted by a translator or an agent, proposed to a daring and caring publisher and promoted efficiently enough to be heard of by the audience — that last part being by far the most difficult task to achieve.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

This question immediately brings to my mind the case of Olivier Mannoni who recently accepted to deliver a new translation of Hitler’s Mein Kampf into french and then wrote an essay about this harrowing experience. His essay Traduire Hitler brilliantly highlights the power and responsibility lying within the very act of translating. The preexisting French version was smoothing over Hitler’s language, giving relative lightness and elegance to a text that one can only describes as boggy, clunky, full of repetitions, approximations and language misuses. How misleading can such an embellishment prove! This is obviously an extreme example, but we shouldn’t forget that the translator is fully responsible for transmitting the essence of the author’s message, even when they don’t fully agree with it. This is specially true in the case of less widely spoken language, when the publishers — and the readers — often finds themselves in a position where they can only trust the skills and ethics of the translator.

As long as the essence and primary intention of a text is respected, I feel like translators can use a bit of freedom to craft a rendition based on their personal reading. I don’t believe in right or wrong, but in precision and rigour. I’ve been trained as a classical musician and I cannot help but draw a parallel between translating a book and interpreting a piece of music. You could give the same music score to ten sensitive and skilful musicians, you would inevitably end up with an equal amount of distinct renditions. You could record one musician playing the same piece everyday for a year, you would end up with 365 different versions of it. None of them being the right one. The way a text travels from a language to another deeply depends on the translator’s sensitivity, literary and personal background, linguistic and human experience of the area where the story takes place, etc. That’s part of the beauty of it and that’s why trusting AI with translating literature would be (is) such a shame. AI is trained to always come up with the most probable solution, not with the most sensitive or creative or surprising or ambiguous or…

Speaking of ethics, some translation issues have been widely discussed among translators and academics (the conservation of metrics and rhymes in poetry, the adaptation of degrees of politeness in dialogues, the use of footnotes, etc…) and the different approaches are often fiercely defended by some passionate advocates. I must admit that, on most of these topics, I am not in a position to express such a forthright opinion as some of my colleague do. On the contrary, I find it important to keep questioning my practises on a case by case basis.

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

Even though a lot still needs to happen, I think it’s important to rejoice over what has already been accomplished. In France, we seem to see slow but sure advance in the fields of rights awareness and visibility, in great part thanks to the indefatigable work of the French Literary Translators Association (ATLF), founded in 1973, and to the École de Traduction Littéraire, a one-year professional training targeted at already active translators which was created in 2012 by the French National Book Center.

Nowadays, the public is offered literary festivals focusing on translation, libraries and bookshops sometimes organise translation slams, some podcasts interview translators, a few schools start to organise occasional translation workshops, etc. It’s a slow process but the gain of recognition is really happening.

The professional life of a translator has often been associated with loneliness and invisibility, but the truth is that we have more and more opportunities to speak of our work and to exchange with colleagues. Some translators are doing a great job by writing a blog; both the ATLF and the CEATL (European Council of Literary Translator’s Associations) have launched a Discord server where translators are able to communicate with each other, ask for advice, promote their work, share their experience, etc.

A hashtag has also been created to denounce publishers, festivals, journalists whose content omits to mention the name of the translator: #citetontrad is standing for «cite ton traducteur», which means « name your translator ».

Could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

Obviously, publishing foreign literature is only meaningful and necessary because it can open a door to enter another reality, to discover another way of looking at life. Otherwise, why not be satisfied with the literary production of one country? One town? It might sound very much like a cliché, but reading translated books is all about tasting the precious diversity of existence, it’s all about realising that we are overall more alike than different but that the differences are to be cherished.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

**INTRO Photo © Laure Villain

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE