Claudiu Sfirschi-Lăudat is a translator of Greek literature in Romanian and director of the Branch of the Hellenic Foundation for Culture in Bucharest. He studied at the Philosophy Department of the University of Bucharest and chose the dramatic genre as a form of artistic expression. He is the author of the theatre play Obsessions, based on texts by Margarita Karapanou, directed by Yannis Paraskevopoulos at the Cultural Centre Artcub, in 2016. The play was selected to be performed in the National Theatre Festival (FNT), in 2016, and took part in some of the most prestigious Romanian festivals. In December 2018, his play A History was performed as a radiophonic theatre show at the National Cultural Radio Station. His play Green Riding Hood, directed by Ștefan Lupu, is performed now at “Ioan Slavici” Classical Theater in Arad.

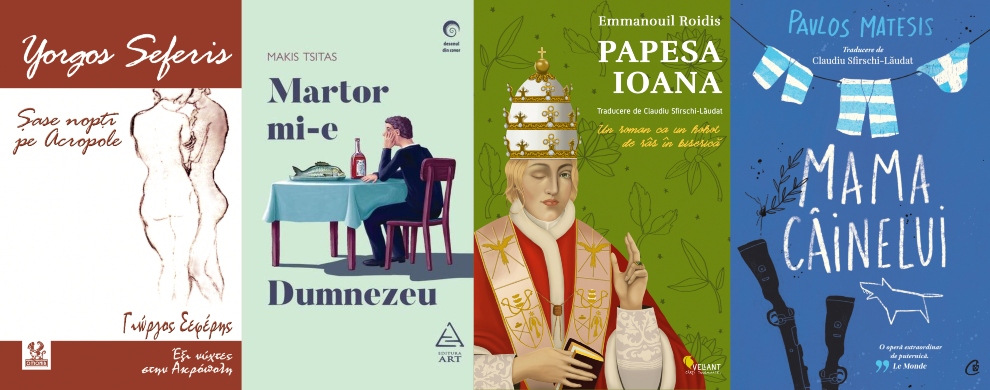

He has translated significant Greek writers such as George Seferis, Emmanuel Rhoides, Georgios Vizyinos, Nikolaos Mavrokordatos, Evangelos Moutsopoulos, Eleni Ladia, Aris Alexandrou, Pavlos Matesis, or contemporary ones, such as Makis Tsitas. He also translated short texts for different cultural publications and theatre plays(Lysistrata by Aristophanes, for the National Theatre of Craiova, and three theatre plays for Nottara Theatre, included in the volume Contemporary Greek Dramaturgy / Dramaturgia contemporană greacă, Fundația Culturală „Camil Petrescu” & Teatrul Azi, 2019). In 2008 he was awarded by the Hellenic Society of Literary Translators (Athens) for the best foreign translation of a Greek book, namely for Six Nights on the Acropolis by George Seferis (2007), and in September 2021, he received Premio Autore Internazionale 2021 from Sindicato Nazionale Autori Drammatici e Radiotelevisivi, at the „Schegge d’autore” Festival, 19th edition (2021).

He has created, together with Simina Popa, the podcast Față/Verso, dedicated to various cultural subjects – such us contemporary literature and theater, or translation from “minor” languages –, and he published last year an anthology of literary and philosophical texts about olfaction from Antiquity to today (Osmé. An Anthology for everyone’s nose, Peter Pan Art & Entheos, 2022).

What triggered your interest in the study of the Greek language and literature? More specifically what led you to the translation of Greek literary works?

In my university years – ah, how much time has passed since then, the line of blown candles that Cavafy referred to is getting longer – I studied philosophy and ancient Greek language at the University of Bucharest. I then had the desire to study and read the ancient Greek philosophers in the original and thus the foundations of the Greek language were laid. The fact that the Greek language has been spoken continuously since the darkest times until today was a motivation to also occupy myself with modern Greek. And as nothing in life is a coincidence, the first encounter with Greek literature was through George Seferis’s novel Six Nights on the Acropolis, which by chance – but we have already said that there is no such thing – I discovered in an Athenian bookstore. I was not aware at the time that Seferis had also dealt with prose and, since I did not dare translate poetry, I thought that there was no better way to access poetry than to translate a poet who chose to express himself through prose as well. So, my first translation was both an exercise in Greek, but at the same time a starting point for this translation work that eventually contaminated my blood, to become an addiction, which made me a real translation addict.

Later, one book led to another, with a natural rhythm, because each book that I chose to translate appeared in my life at its right time, at a stage when I was ready to understand it, assimilate it and transfer it to my native language. I should not overlook the fact that almost all of these books came into my life through meaningful encounters with people (including authors) who, so to speak, opened my eyes: Margareta Sfirschi-Lăudat, Hellenist, who taught me both ancient and modern Greek, Elena Lazăr, translator and director of the Omonia Publishing House, the philosopher Evangelos Moutsopoulos (I translated two of his books, The Pleasures and The Values), Eleni Ladia (I translated two of her books: The woman with a ship on her head and Fragmentary relationship), the neo-Hellenist Jacques Bouchard (to whom I owe my interest in the “novel” Philotheos’ Parerga by Nikolaos Mavrokordatos, in Margarita Karapanou and Pavlos Matesis), Makis Tsitas (whose Witness is my God I translated into Romanian) or the writer, scholar and translator Victor Ivanovici, who years ago spoke excitedly to me about The Box of Aris Alexandrou at some Thessaloniki International Book Fair.

To answer your question, my interest stems from this interweaving of books and people, which I deem necessary, because I don’t consider myself a professional translator – I don’t do it intensively nor do I work by order –, but rather an eternal lover of the art of language who can’t do without love and who performs an art he feels he will never master.

Which were the main challenges you were confronted with while translating major Greek writers, into Romanian?

The Greek element, that is, how intense it is and whether it can be perceived or understood by the Romanian public. Usually historical references, references to Greek events or to local or temporal contexts, are quite difficult to understand for a foreign audience and in these cases the translator is forced to explain them in footnotes which, if numerous, make reading difficult, distract attention and disrupt the flow of speech. For this reason, I have chosen works which, beyond their “Greekness”, confer a universal message that is, in my opinion, accessible to a foreign audience.

The Box by Aris Alexandrou, for instance, alludes to historical events, but its message is understood by any reader, regardless of history, language and culture. The same goes with the other works I have translated: God is my witness, The dog’s mother or Pope Joan. Another challenge is to find the right flow of language, to render the idioms or overtones of a dialect, to disguise a foreign language with the words of your own and, after all, to play the role of the book’s characters yourself, lending them your own voice, which has to be a transparent one lest it conceals the original. A very difficult task, isn’t it?

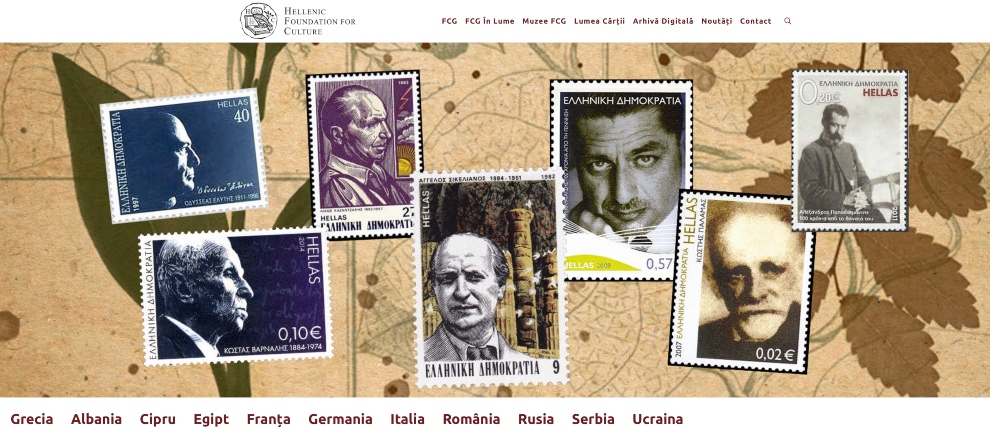

Since you are director at the branch of the Hellenic Foundation for Culture in Bucharest, tell us a few things about its role and initiatives for the promotion of the Greek language and culture in Romania.

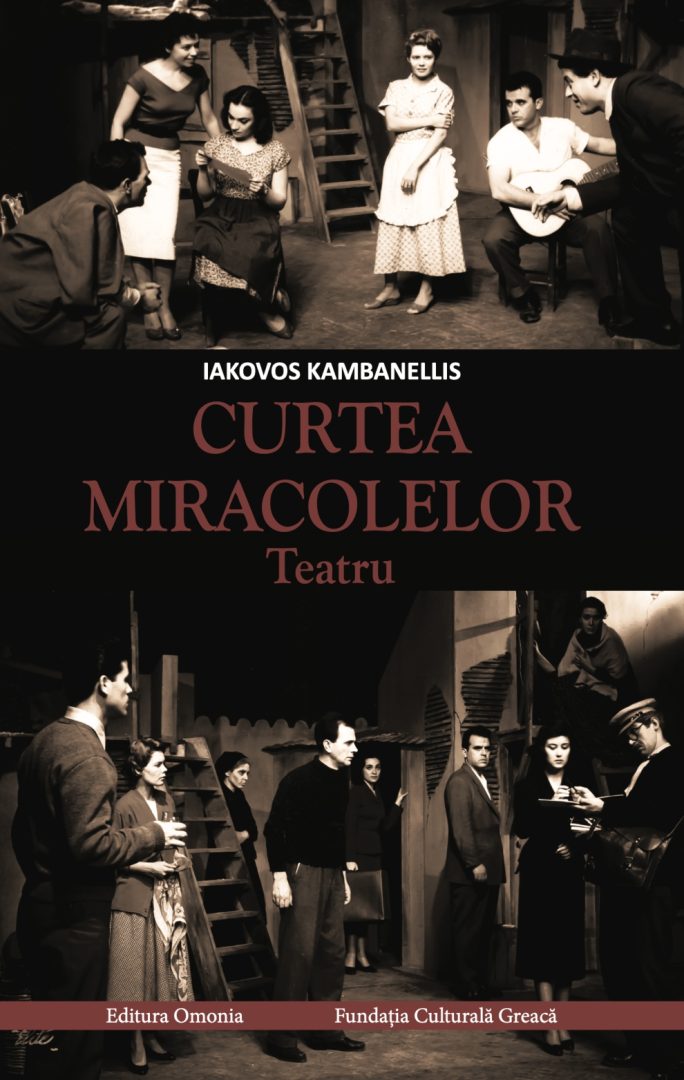

Since its establishment in Romania, in 2008, the Branch of the Hellenic Foundation for Culture in Bucharest has continuously promoted the Greek language and culture through Greek lessons for adults and diverse cultural activities: theater and dance performances, exhibitions, participation in local cinema festivals (this year with the film Tailor at the Cinefemina festival and with the film Magnetic Fields at the European Film Festival), book publications (last year at Omonia we published an edition with three plays by Iakovos Kambanellis), translation workshops, theatrical lectures, such as the presentation of three Greek theatrical texts at the Nottara Theatre, or regular participation in the joint actions of the local EUNIC hub (this year with the Greek philosopher Theofanis Tassis at the Night of Philosophy, on May 25). The Romanian public is quite demanding and we have to be careful with our choices. In the Bucharest branch we try to present an image of the contemporary cultural scene, without of course ignoring the heritage of the precious cultural history of Greece. One such approach was the realization of a season of the Față-Verso podcast dedicated to the Revolution of 1821, in which we tried to look at the past from the vantage point of the present day, in a playful and accessible manner for the young audience, but with valuable information for any type of public. More information about our actions can be found our website: hfc-worldwide.org/bucharest.

How familiar are Greek readers with Romanian literature? And, in turn, what is the appeal of Greek literature in Romania?

Thanks to the Romanian publishing house Omonia, founded in 1991 and covering two thirds of all translated Greek works published in Romania in the last 30 years, the Romanian public can enjoy some of the greatest works of Greek literature. However, apart from the effort made by Omonia Publications, which, we have to admit it, is a very small business, the interest of Romanian publishers is minimal – to zero -, which I personally find quite paradoxical since I reckon the conditions for a favorable acceptance of Greek literature in Romania exist: more and more Romanians spend their holidays in Greece, the long-standing relationship between the two peoples, the common mentality and so on.

Therefore, a great personal bet for me is to convince the Romanian publishers that the works I have chosen are worth it. And, unfortunately, the fact that they “are worth it” often has nothing to do with their literary value. The criteria that usually govern the choices of the publishers here have more to do with the financial value of the books, with the prizes they have received, with the number of copies of the selected book and not so much with its place in the history of literature and culture in general. When you propose established authors such as Seferis, Matesis, Karapanou, Rhoides or even Tsitas, who is a new author but has received an important prize (of the European Union), you think that the doors of the publishing houses would open at the first contact. Not really!

Most of my translations had to wait four or five years before a publisher was convinced, but even then more by the value of the translation than by the value of the book. That is why I have come across a “sideways” strategy to pique the interest of the editors and of the public for the Greek literature: to present Greek literary texts through theatrical performances, for example, based on my own adaptation. This is how the play Obsessions was born, based on texts by Margarita Karapanou, following some failed attempts to convince Romanian publishers to publish her works, or a theatrical performance based on The Dog’s Mother by Pavlos Matesis, or even an anthology of theatrical plays translated into Romanian, which I sent to Romanian theaters or to Romanian directors and actors.

Aside from the effort to seduce publishers, there is also the effort to help promote the books, after they are published. That’s because lately the translator, besides his primary job, has undertaken the (unpaid!) role of the advertiser. Having in mind this intension of helping to promote a book and confirm the trust the publisher placed in the book I’ve proposed to him, I created, for instance, a Facebook page for Pope Joan, which, in a ludic tone, address directly to the public.

It has been argued that when translating from a so-called “minor” language, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power? Can translation ever be unethical?

The translation of the Bible is a case in point: power is held by whoever owns the prevalent language. Yes, I reckon the translator has some power, which is balanced by the corresponding responsibility of transferring a concept from one language to another. We all know the cliché saying “traduttore traditore”. Some translators agree, others disagree. The truth lies somewhere in the middle. Of course, something is always lost in translation, but this isn’t something the translator willingly aim for. After all, the work of all translators is governed by the ideal of faithful translation, but to what extent can we be faithful in everything we do? If one has erotic dreams, does this mean that one is not faithful to his or her spouse? I’m just wondering… (and kidding). So, we are both ethical and unethical. We are not unethical as long as we respect the other – the author, the reader, the publisher. We are unethical when we betray the original a little, so that the text can be heard naturally in the language into which we translate it. The most important thing is not to force them.

Do you agree with those who argue that if the author is the protagonist, the translator is the invisible hero? How important is the role of translation in the dissemination of a literature beyond national borders?

Translations play a decisive role in enriching a country’s culture. It’s how the public has access to sources of knowledge that would otherwise be unapproachable or unknown to them. At this year’s International Book Fair in Thessaloniki, I was impressed – once more – with the number of foreign literary translations and studies in the Greek language. Unfortunately, there is no equivalent in Romania. There are still missing some important studies or literary works in Romanian translation. And you can find this out if you try, for example, to do a PhD. You would then realize how many tools are missing, due to the lack of translations. So how can someone offer something if they haven’t received it first? Culture is an ongoing exchange, but there must be a product to exchange.

So yes, the translator plays a significant role, although at times behind the scenes. Yet, lately, translators seem to have come to the forefront, given that their name is more and more often present on the cover; they are invited to open discussions or meetings with colleagues, authors and publishers, while apart from their job, they have undertaken public relations as well. We’ve got a little bit left and we’re dancing in order to promote the works we have translated with so much effort. And, of course, free of charge, since we all know that translators are cultural beings, and as such, they need no food, no drink, just ideas to be fed.

GreekLit, a new translation funding program has recently been launched by the Ministry of Culture. How important are such initiatives for the dissemination of Greek Letters internationally?

I have been waiting for EKEBI’s old translation support program to be revived, and I am glad that GreekLit is now up and running so as to support the efforts of foreign publishers and translators. However, I take the opportunity to note that the amount covered through GreekLit is small for the Romanian standards, since the program only covers 75% of the cost of translation, which is the lowest in relation to the total cost of publishing a book – at least in Romania. I think Romanian publishers would show more interest if the amount would increase. But even so, its operation is a success and a proof of that is the publication in Romanian of two great books, The Dog’s Mother last year and The Box this year. We’re still waiting to hear back about the fund for another book, Last Black Cat by Trivizas, and I hope that more titles will follow – Iordanidou’s novel, Loxanda is ready and I’m searching for publishers.

Another important support is the EU’s Creative Europe translation program which, in addition to the satisfactory amount allocated to the translation, requires publishers to have a strategy for promoting the translator, which I consider essential. It would be good if there were grants or workshops for translators and generally more opportunities for cooperation and meeting with each other to exchange opinions and experiences.

*Interview and translation into English by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE