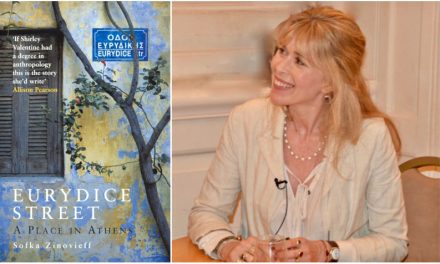

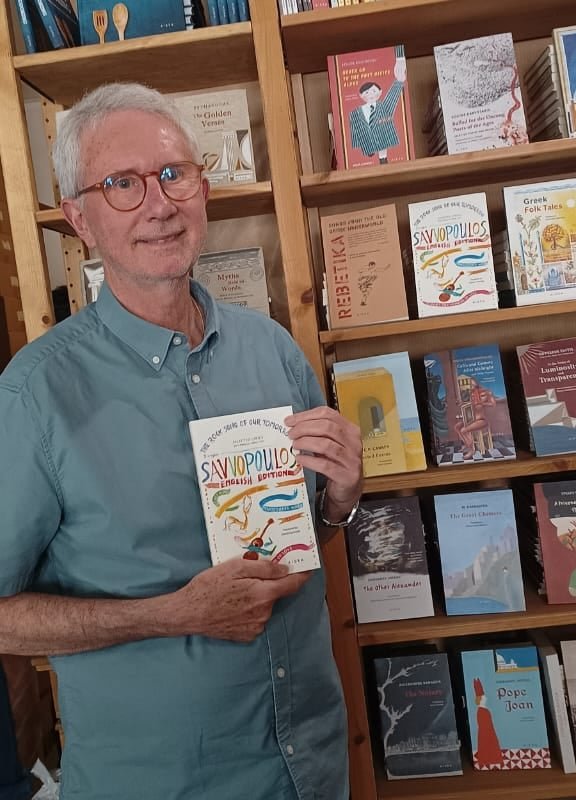

David Connolly was born in Sheffield, England, and is of Irish descent. He studied Ancient Greek at the University of Lancaster, Medieval and Modern Greek Literature at Trinity College, Oxford, and received his doctoral degree for a thesis on the theory and practice of Literary Translation from the University of East Anglia. A naturalized Greek, he lived and worked in Greece from 1979 until his retirement in 2014, teaching translation studies at undergraduate and post-graduate level at a number of Greek university institutions. His last position before retiring was as Professor of Translation Studies at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He has written extensively on the theory and practice of literary translation and on Greek Literature in general and has published over fifty books of translations featuring works by major Greek poets and novelists. His translations have received awards in Greece, the UK and the USA.

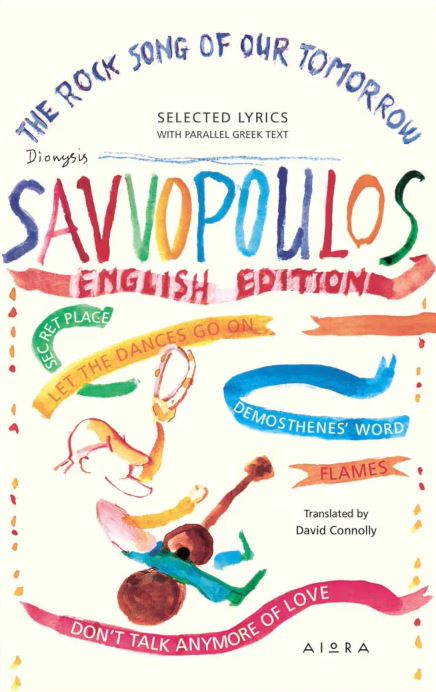

Your latest translation venture The rock song of our tomorrow: Dionysis Savvopoulos English Edition, the first anthology of Savvopoulos’ lyrics to be published in English translation, received quite favourable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book and the main challenges you were faced with.

The idea for the book belongs to Aris Lascaratos and Nicoletta Sarri at Aiora Press and I was delighted when they shared their idea with me and proposed that I undertake the translation. Every translation is a different (ad)venture with its risks and its rewards and translating lyrics was a new challenge for me, somewhat different to translating poetry or prose fiction. Rhythm is all-important in all literary writing, but even more so in texts written specifically to be set to music. I would say that trying to render the rhythm or, at least, a corresponding rhythm was probably my main concern during the translation process. Similarly, most of Savvopoulos’ lyrics are also rhymed and this, too, presents a special challenge for the translator. My overall approach in this respect was to reproduce the rhymes where this came fairly easily and where it didn’t require sacrificing too much the semantic content of the verses.

Of course, the choice of lyrics to be translated is also part of the translation process. My aim was to make a representative selection of lyrics from Savvopoulos’ entire discography but, at the same time, I chose those lyrics which most lent themselves to translation. For example, some lyrics would lose so much in translation that translating and including them in the selection would be a disservice to the author.

I should add that the book is bilingual (Greek/English) so that, although primarily intended for a foreign readership, it constitutes a representative anthology of Savvopoulos’ lyrics in Greek for the Greek reader too. It contains 34 songs from his 10 original albums. All the songs included can be heard in their original Greek renditions by scanning the QR code in the book. Similarly, four of the songs can be heard in English translation and were recorded by Alkinoos Ioannides, Elli Paspalia and Elina Baga specifically for this book. The book also contains two brief introductory texts by Dimitris Papanikolaou and Dimitris Karambelas, both experts on Savvopoulos’ work.

“I didn’t translate the lyrics so that they could be sung with the same melody in English. My aim in this book was to introduce the lyricist Savvopoulos to an English-speaking readership”. Tell us more.

The translator’s aims are all-important as they determine the translation approach. Translating the lyrics so that they could be sung in English to the same melody would have required a completely different, much freer, translation. I have always believed in the possibility of close translation of all the various aspects of a literary work (content, form and effect) and in this translation, too, I endeavoured to render the lyrics as closely as possible in English and as literary texts that could be read independently of their musical accompaniment. It is a feature of many modern singer-songwriters that their lyrics can be read and appreciated as literary texts in their own right. One only has to mention Bob Dylan (Noble Laureate for Literature) or Leonard Cohen or Paul Simon. And, in my opinion, Savvopoulos’ lyrics fall into this category.

Would you say that the lyrics of Savvopoulos may help English-speaking readers to get acquainted with the history of Greek society during the second half of the 20th century?

Many of Savvopoulos’ lyrics undoubtedly offer a social commentary on the rapidly changing face of Greek society in the latter half of the 20th century. They often refer to specific social and political events and require some explanation for the non-Greek reader. To this end, the book includes notes to help the reader understand these references. The sensitive reader will undoubtedly be left with a picture of Greece very different to the one often presented by tourist organisations. But these lyrics go even further and offer an insight into the hearts and souls of a whole generation of Greeks: into their hopes and disappointments, their struggles and defeats, their joys and sorrows. It is not surprising that many of Savvopoulos’ lyrics have become proverbial precisely because they reflect the expressive needs of this generation.

How did your involvement with Greek language and literature begin? What continues to be your driving force decades later?

Something about Greece resonated with me at a very early age. It became the “Promised Land” of my adolescent years, during which I read everything available concerning Greece and Greek literature. I remember, for example, being fascinated by the idyllic descriptions by Lawrence Durrell and Patrick Leigh-Fermor of life in pre-war Greece, but I also read the relatively few books by modern Greek authors then available in English translation (Cavafy, Seferis, Kazantzakis). All this inspired me to study ancient Greek at university and then to move on to the study of medieval and modern Greek literature. There was no question in my mind that I would come to live in Greece upon completing my studies in the UK, which is what happened. In Greece, I have to be honest and say that I somewhat drifted into translation, but it soon became something of an “addiction”. My deep love of the Greek language and of Greek literature motivated my desire to want to share what I considered to be gems of Greek literature with an English-speaking readership and to give the Greek poets and authors that had moved me a place on the international stage. This was always and continues to be the driving force behind my professional work.

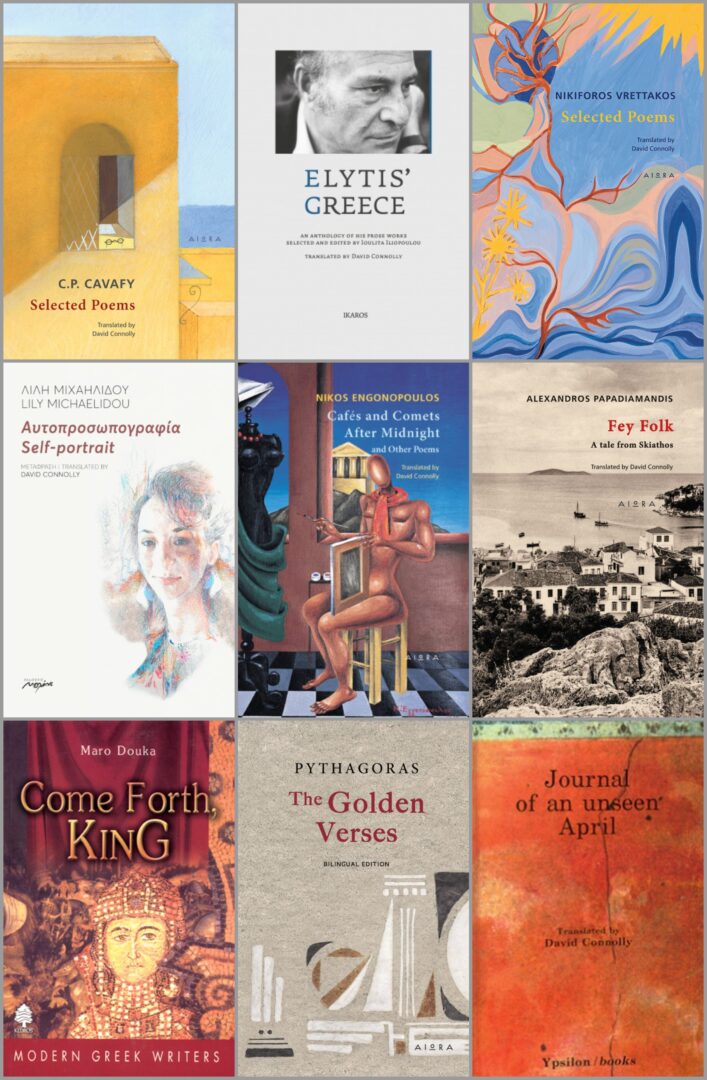

You have translated major Greek poets including Cavafy, Engonopoulos, Elytis, Vrettakos, Dimoula, Ganas and also prose writers such as Rhea Galanaki, Maro Douka and Petros Markaris. What are the main challenges a translator faces when translating Greek literature? How have you coped with them?

I won’t talk about the technical challenges facing the translator as these are many and often very different for each individual poet and author. The main challenge facing the translator of Greek literature is to convince foreign publishers, agents and readers that Greece has significant contemporary poets and authors who deserve a place on the international stage. The promotion of modern Greek literature abroad is not helped by the fact that it is written in what is a language of limited diffusion or by the fact of Greece’s position, literally and metaphorically, on the fringes of Europe. Similarly, most foreign readers still associate Greece with its glorious past or with its image as an “exotic” tourist destination, factors which create certain expectations among the foreign readership. The international success of books by foreign writers on Greek themes or with Greek settings which meet these reader-expectations provides ample evidence of this. The translator of Greek literature is obliged, therefore, to act also as a literary agent and promoter and, to this end, I have given a great deal of time and effort to attending and talking at conferences and events abroad. Of course, in order to cope with this aspect of the translation business, the translator requires the support of an effective policy on the part of the Greek State, together with the active participation of Greek publishers and of the Greek authors themselves.

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, literary translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

It is a fact that without literary translators, the great classics of world literature would simply not be available to most readers. How many people, for example, would be able to read the ancient Greek epic poets and tragedians or the great Russian novelists if not for the arduous and painstaking work of translators? Yet, historically, literary translators have not been given the credit they deserve. They were regarded as hack writers, were underpaid and their importance was generally ignored. And even today, very little would appear to have changed if we are to judge from most reviews of translations of literary works. Reviewers tend to have little or nothing to say about the quality of the translated work other than general remarks of a highly subjective nature, usually confined to the end of the review as, so it often seems, a kind of afterthought. Similarly, publishers often confine the translator’s name to the small print and offer extremely low fees.

Thankfully, things have started to change somewhat in the last fifty years or so. The rise of Translation studies as an academic discipline has done much to highlight the importance of translation, while courses in literary translation have produced a new generation of professionally-trained translators. Translators, too, in this period have organised themselves into associations with required professional standards and recommended translation fees. Translation conferences, events and prizes are also helping to raise awareness among publishers, reviewers and the reading public concerning the important role of the literary translator. But there is still a long way to go.

Could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

I think this is a good description of what translators actually do rather than a question of what they could do. Apart from its importance for the transmission of literary works, translation has always been instrumental in the dissemination of knowledge, religion and culture in general. Languages and cultures are promoted by the process of interaction and osmosis and one of the most effective means in this process is translation. Translators are, by definition, linguistic and cultural ambassadors and should be recognised as such.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read also: BOOK OF THE MONTH: The Rock Song of our Tomorrow – Dionysis Savvopoulos English Edition; Reading Greece: Aiora Press, a Publishing House that Promotes Greek Literature beyond National Borders

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE