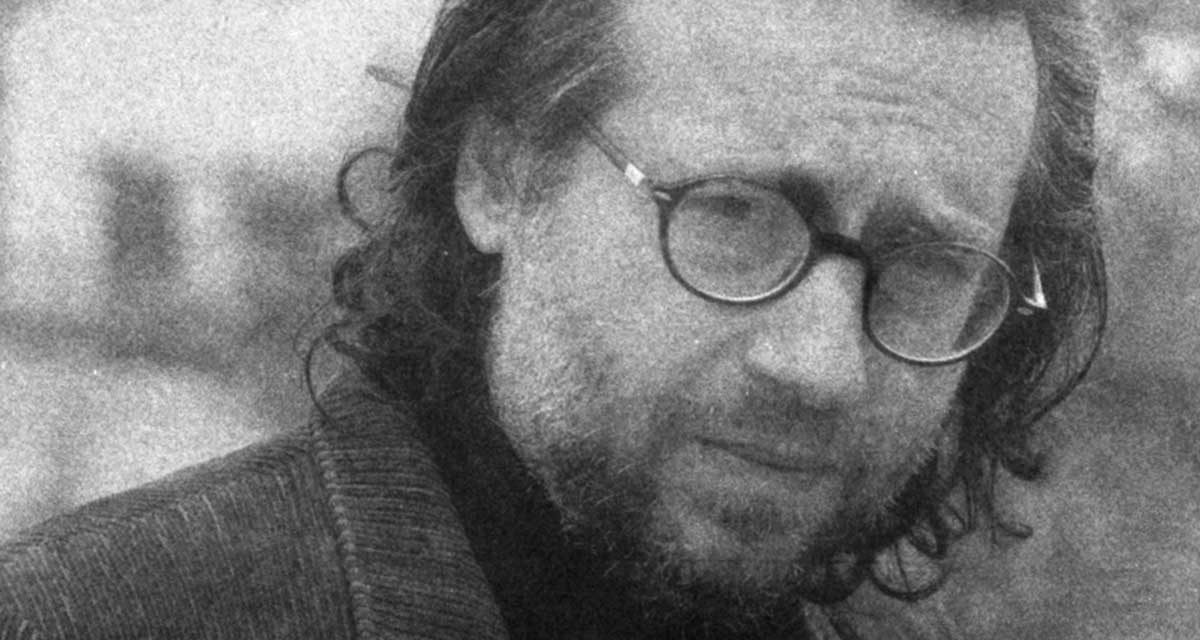

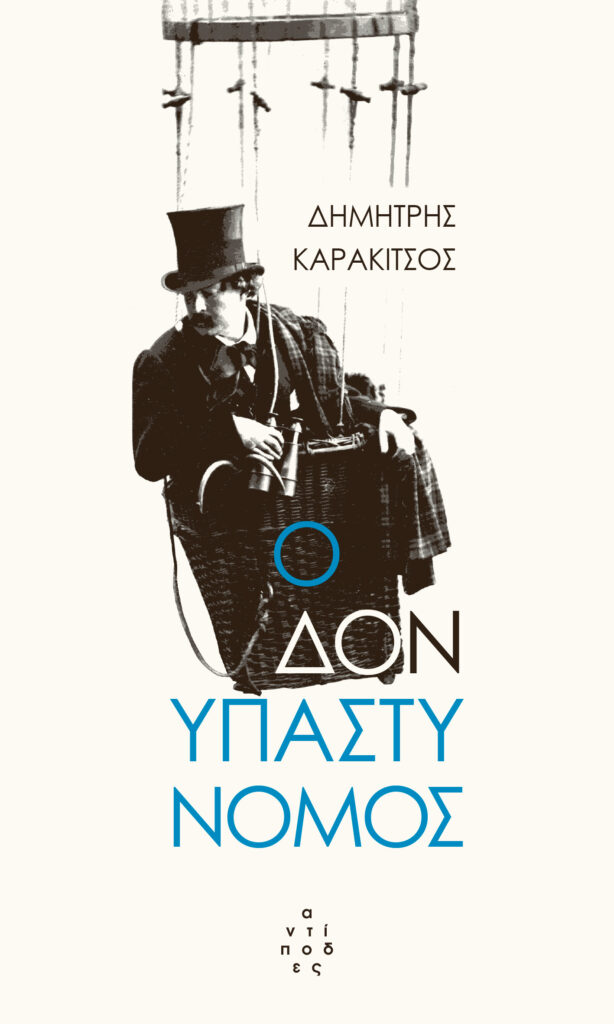

Dimitris Karakitsos was born in Volos in 1979. He has published the following books: The Cats of D. I. Antoniou, Poet (To Rodakio, 2012), Venusberg (Antipodes, 2015), Wrestlers (Potamos, 2016), Stories by Bartholomew Olivier, Receptionist and Short-story Writer (Potamos 2017), Zacharias Scrip (Potamos, 2019), Mancha stories (Thraca, 2020) and Don Corporal (Antipodes, 2020).

Dimitris Karakitsos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest writing venture Don Corporal, a novel that “draws its aesthetic (and, in part, its plot) from surrealism”, commenting that “in an era when public discourse has been identified with the word austerity, [his] immediate reaction was to search for a baroque language”. He explained that “the past, or rather a perpetual present, in imprinted on our books, yet every moment remains different”, and concluded that the way he perceives literature is as “a person that comes every time bearing a different face”.

Your latest writing venture Don Corporal (Antipodes, 2020) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

The underlying cause is the following: the idea that a modern Don Quixote would most probably be an ardent reader of crime fiction. Yet, Astolfos, the hero of the book, lives in a country where people walk on the ceiling, trees are red, candy stores have moving mirrors and the narrator may intervene in his story like a genuine deus ex machina. In just one phrase: the novel draws its aesthetic (and, in part, its plot) from surrealism.

You have characterized the book as a surrealistic crime novel. Could you elaborate on that?

Let us just ponder first on the centuries-long distinction between the Dionysian and the Apollonian spirit. On the one part, an unbridled surrealism, and on the other, the concrete logic of a crime novel, are both elements I have long wanted to combine. The idea began to materialize during the summer of 2015. I was queuing for hours in front of an ATM (following the imposition of capital controls) and I was just thinking (I had just published Venusberg), being obliged to tolerate all those stray political arguments recycling the same phrases again and again, that language may either have the power to get rid of what humiliates us or is worth the same as a drunk clown. And in this way, while also intrigued by a Cocteau movie, the style of the book began to take shape. In other words, I wanted from the start to push things to their limits.

In his review, Panagiotis Kehagias included Don Corporal “among those, most interesting, books that do not pretend to take place in the real world, but create tensions between the real and the non real, between realism and the vast symbolic system of art”. Where does the real meet the symbolic in the book? What purpose does language play in this respect?

Since we are discussing symbolisms and language, what actually matters is how you decide to perceive the world around you. In an era when public discourse has been identified with the word austerity, my immediate reaction was to search for a baroque language. I was sure that my text would part from everyday life – or is it possible that things didn’t happen this way? What I mean is whether it is possible for a book, for whatever book, not to be a product of its era. I think not. But let us just say that what we call reality has diverse levels. It’s the same landscape, yet each one of us perceives it in a different way.

You seem to experiment with different literary genres: poetry, short story collections, and most recently a novel. What is that binds them together?

Proust wanted to see his work printed in a dense volume; in case one proposed to do the same with my books, I would think that disaster was imminent. The past, or rather a perpetual present, is imprinted on our books, yet every moment remains different. To put it differently: you capture a theme, and the theme, if your ears are open, is ready to relieve you of many troubles. It will offer you the words, the style; it will dictate whether you should write in verse or in prose – as long as you are willing to hear it. Let me give you an example: I often went unprepared to my university exams, yet I didn’t fail because I carefully read and reread the question. I tried to understand what it required from me.

How does literature converses with the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to describe what could potentially be radically different realities?

I may not sure it does that. At least, it exists, and this is enough on its own. There are books and there are libraries; torn, old or freshly published books, books not still written or books that are trying to be written. There is the paper and the keyboard, there is the imagination, freedom, the ability to erase and to rewrite. That’s how I perceive literature: a person that comes every time bearing a different face.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE