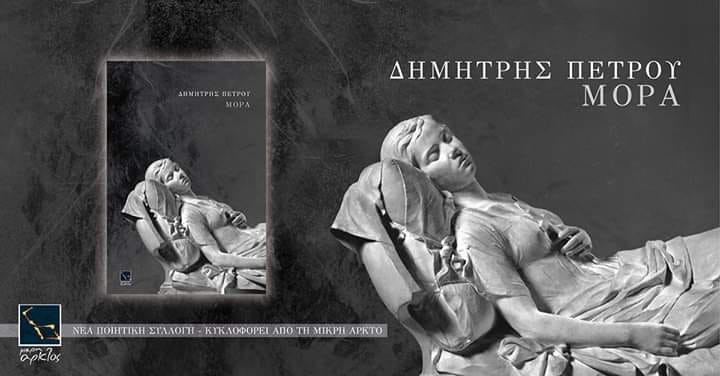

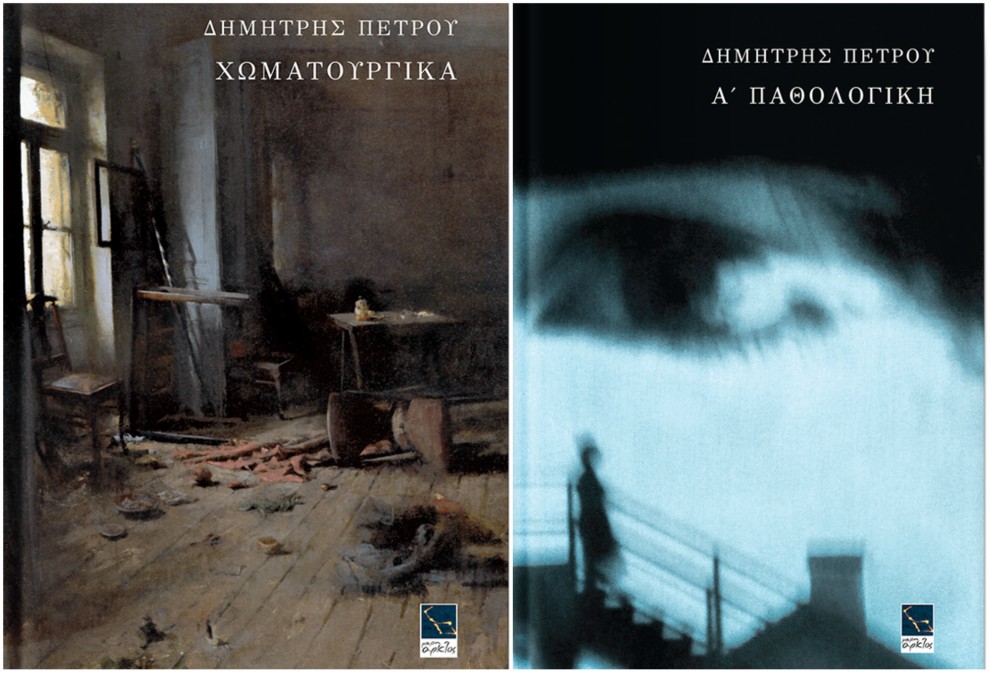

Dimitris Petrou was born in Drama, Greece (1970) and he lives in Athens, Greece. He has written three poetry books: A’ Pathologiki [Medical Ward A] (2013), Chomatourgika [Land works] (2016) and Mora (2018), all of the them published by Mikri Arktos editions.

Dimitris Petrou spoke to Reading Greece* about his three poetry collections noting that he considers them “a trilogy”, where “portraits, landscape and tradition shaped the wheel of a micro-history, which has gone full circle”. He explains that the common ground in all his books is “free verse, everyday non-poetic words and inner rhythm”, and talks about his “writing haunts”, “double negation to achieve positive meaning, small cracks to reveal something new, illusions and expectations intertwined, death as catharsis and catharsis as the ritual of healing”.

Asked about the influence the poets of the 1970s exerted on his writings, he notes that he does “feel emotionally engaged with their work”, but his concern is “to extend his reach and try to comprehend our poetry in its totality”. He concludes that “current Greek literary production seems to be promising”, yet “only time will tell whether the poetry of this new millennium deserves a special place”.

Your third poetry collection Mora was recently published by Mikri Arktos. What differentiates the book from your first two writing ventures both in terms of form and content?

Free verse, everyday non-poetic words and inner rhythm create a certain atmosphere in my books and that’s their common ground I believe. To comment on the differences among them, in terms of context, my debut poetry collection A’ Pathologiki (Medical Ward A) was a close up on the interpersonal pathology of the family and its individual members in an attempt to achieve self-realization.

In my second book Chomatourgika (Land Works) I am an overwhelmed observer staring at the scenery of northern Greece in Macedonia with awe and dread. That was a way to talk with respect for the land, its harvest and also think of the landscape as a geography of the human heart and soul.

Now, my recently published third book, Mora is a story about loss, death and revival. Mora, the central figure of the book, is the bringer of nightmares, the dark female spirit found in legends and mythologies around the world, which disturbs people at night. Mora comes to people while they sleep, sits on their chest so they cannot move or breathe until dawn. For me, Mora is a symbol of the subconsciousness and a synonym for anything or anyone who can make our lives unbearable; an alter ego, a trauma, a crime, a mistress or even poetry itself.

Although, our imagination can run wild, collective memory runs faster. That’s why I’ve chosen to pay a small part of the enormous debt I owe to folk poetry and demotic tradition. Mora’s voice comes from that tradition and in terms of poetic form that’s the main difference between the third book and the previous two.

I consider those three books to be a trilogy. Portraits, landscape and tradition shaped the wheel of a micro-history, which has gone full circle.

Illusions, ruptures, expectations, negation, death and catharsis. Would you agree that they constitute recurrent themes in your writings?

My writing does feature recurrent topics or emotional tensions. The themes, or to be more accurate, the conditions you mentioned can be considered as “haunts”, writing haunts which give you insight about yourself, your poetry and the story you are trying to tell. I’ve learnt not to fear them, as long as I’m crafting fresh context for them. Double negation to achieve positive meaning, small cracks to reveal something new, illusions and expectations intertwined, death as catharsis and catharsis as the ritual of healing.

To use Barbara Roussou’s words, «Petrou manages this coupling which makes his poetry both realistically confessional and highly perceptive”. What purpose does language serve in your writings?

Poetry is a separate language, a language within a language. Ordinary speech – both written and oral – is simple, straightforward and it’s meant to communicate a message. On the contrary, poetic expression purposefully includes imagery and figurative language to convey a deeper meaning. So, if my work has been received as realistically confessional and perceptive at the same time, it’s only because I’ve been trying to find and offer something heartfelt and solid.

How do you respond to those who argue that your poetry has been greatly influenced by the late works of poets who belong to the generation of the 1970s?

Poets of that generation are among my personal favorites. I do feel emotionally engaged with their work and I have to admit that there are whole books truly valuable to me as a reader and re-reader. However, this generation is not the immediately preceding one. Important poets appeared the following decades and from the writer’s perspective, my concern is to extend my reach and try to comprehend our poetry in its totality. I mean its continuity, the inside narrative of it.

What is the effect of reality on poetry? And, vice versa, how is reality re-formed/trans-formed in poetry?

The bad news is that reality is too persistent. Poets, though, are lucky enough to fit things into their version of reality. Are they disillusioned, disheartened? No – they just choose personal truth over stark reality. An old proverb says ‘who’s talking the truth, does not need a lot of words’ , neither poetry, I would add.

“What most distinguishes the poetry of this new millennium from that which came before is, on the one hand, its diversity – there are no clear-cut schools or factions – and, on the other hand, the cultural conditions that it takes for granted”. How would you comment on current literary production in Greece?

Current Greek literary production seems to be promising. It moves fast, it has diversity and it is independent. I’m not sure if these qualities are enough to keep poetry getting richer. This frantic pace reminds me of the always present quality/quantity debate. Most books have a shelf life of 30 to 60 days and even a committed reader can miss out on pleasures of reading a good book. Only time will tell whether the poetry of this new millennium deserves a special place.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE