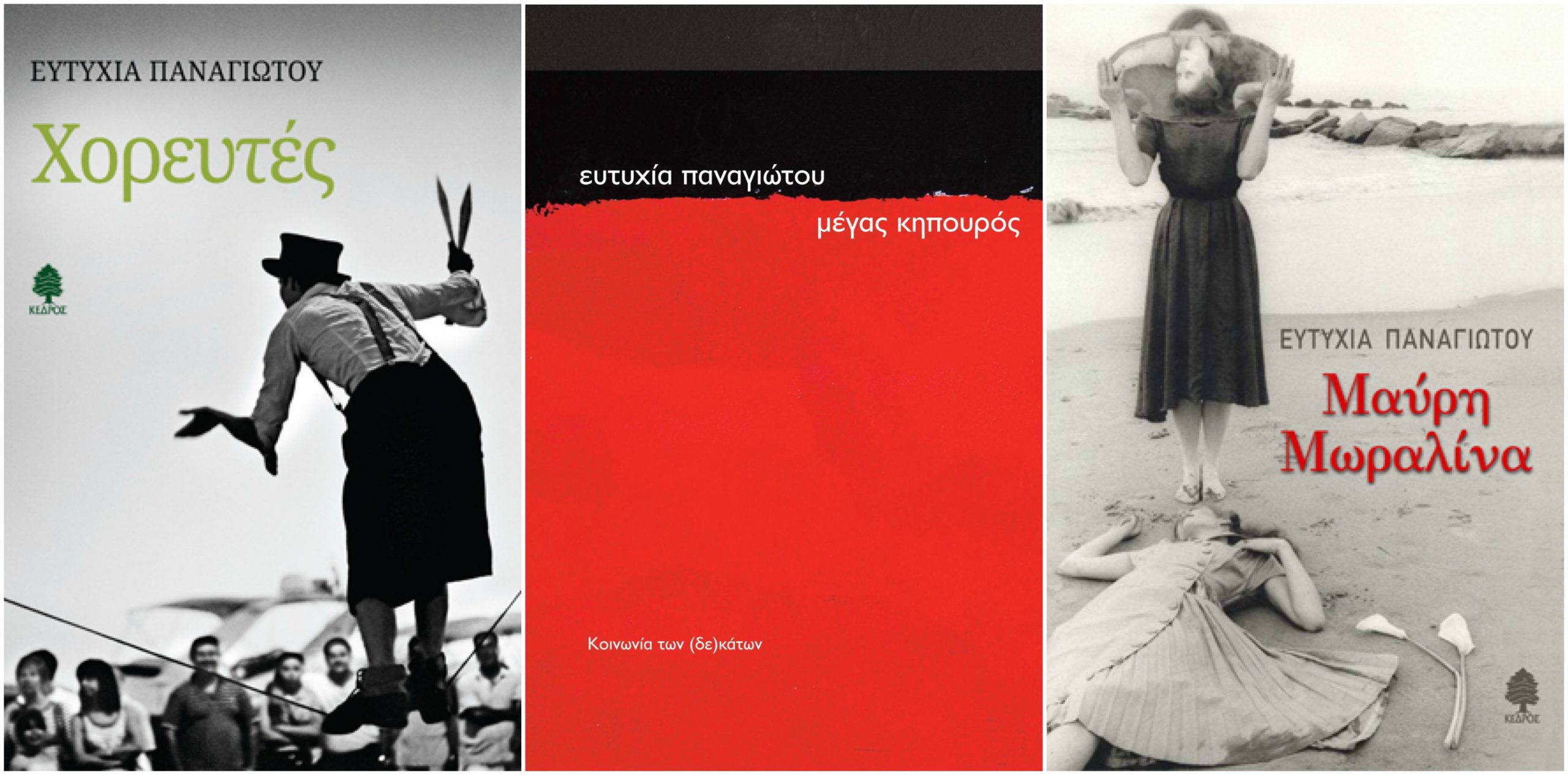

Eftychia Panayiotou (born Cyprus, 1980) is a poet, copy editor and poetry translator (Anne Sexton, Anne Carson, English Romantics). She wrote three books of poetry: μέγας κηπουρός (great gardener, 2007), Μαύρη Μωραλίνα (Black Moralina, 2010, third prize for best book by young poet), and Χορευτές (Dancers, 2014, shortlisted in Cyprus and Greece). She studied Philosophy and Modern Greek Studies and has completed her Ph.D. in Modern Greek Poetry. She also teaches in creative writing programs/workshops and is engaged with videopoetry and soundpoetry.

Eftychia Panayiotou spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes her poetry touches upon, noting that her last two books “are concerned with the complex relation between history and humans; with narratives of experience, language, literature, politics in specific ages and places”. She also comments on the main challenges she was faced with while translating major American poets, explaining that “it is difficult to be exact through analogy and diversion, through space/times lapses, but you need to fight to deliver the poem in your language”.

Asked about the interrelation of a national poetry with a foreign audience, she notes that “the concern with ‘national’ poetry and ‘foreign’ audiences is slippery, partly because the notion of ‘borders’ is not always evident or applicable in art”, and concludes that “to envision or expect a radical and fast metamorphosis through poetry is simplistic. Poetry though helps us expose or be exposed to the serious and sometimes playful complexity of our ‘realities’”.

You have published three poetry collections so far. Which are the main themes your poetry delves into? What role does language serve in your writings?

It is strange, I’ve forgotten my initial intentions, given that it has been a while since my latest book Χορευτές (Dancers, 2014) came out. All three books are different, but the two last, Μαύρη Μωραλίνα (Black Moralina, 2010) and Χορευτές (Dancers, 2014) are concerned with the complex relation between history and humans; with narratives of experience, language, literature, politics in specific ages and places. They are poetic sequences that adhere to a certain philosophy and structure, but at the same time they are airy or fluid; they have some openness in terms of hermeneutics. One can read between the lines and decide their version of the narrative.

“I partly disagree with those who argue that art just poses questions. It may pose questions, yet it’s exactly those questions that make us think of the answers”. What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits?

I like to think of poetry as a place (‘topos’) one can enter wholly. As a world ahead of its era or of its exact time, unfolding shades of awareness, for both those who write and read. Think of yourself standing among the cracks of history. Shouldn’t you imagine a meaning or a narrative related to your in-between state? It sounds poetic, in the utopian sense, I know, but it can be a real experience as well.

You have translated into Greek major American poets such as Anne Sexton and Anne Carson. Which were the main challenges you were faced with?

Sometimes it is better not to be overcome by fear, once realizing that there is a certain responsibility in translating ‘major’ poets. Maybe it is better choosing the poets you sense you can encounter instinctively. It keeps things simpler. But then you must work hard, stick to the text and explore as many possible cultural implications lying there. Of course it is difficult to be exact through analogy and diversion, through space/times lapses, but you need to fight to deliver the poem in your language. While translating the Love Poems of Anne Sexton I had to inhabit what I considered to be ‘her’ voice, which was an intense experience altogether. While translating The Beauty of the Husband by Anne Carson, in collaboration with the poet Dimitris Athinakis, there were two issues: one was getting the text’s point, because it is never that direct, and yet it is deep and philosophical with intertextual modes. The other issue was to make the language and the tone sound casual, sophisticated and ironic all at once. The Greek language can be a bit over-dramatic at times; we have huge words including compound ones.

Now, I’ve nearly completed the translation of poems by Byron, Blake and Shelley. I have no idea what happened there, but in the beginning I thought it would be impossible to bring three, or more, versions of English romanticism forth in a readable way: meaning both faithful to the text, technically (e.g. rhyme) and in terms of historical implications. Additionally, you need to somehow enmesh a ‘voice’ of those times within a different ideological and ethical frame. Words or ideas don’t mean or impact the same today.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie?

The anatomy of a poem is to some people nitpicking. For scholars and translators, it is necessary to interlace all parts and support the narrative of the poem. The result should sound in the end ‘natural’ and smooth. One may think of ‘authenticity’ within the text here, even though authenticity might also be an illusion.

In recent years the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry has been rekindled, with an increasing number of Greek anthologies being translated in English. What is it that makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

I can’t really answer. The concern with ‘national’ poetry and ‘foreign’ audiences is slippery, partly because the notion of ‘borders’ is not always evident or applicable in art. However, we need translations of high quality and accuracy to make any possible diversities visible and delightful.

I am not an anthology or a magazine person myself, as reader I seem to get frustrated with too many fragmented voices organized with a specific way. Readers only get to read a few poems from each poet and then move to the next one. They/we also get a deficient or deformed view of the poetics each poet demonstrates (that is, of their poetic discourse and world view), given that anthologies or magazines featuring poetic ‘generations’ or groups or ‘aesthetics’, from the original or through translations, many times exclude (or are not aware of?) representative poetics. I think that anyone would feel more or less disturbed once realizing that, nevertheless spending his or her life manifesting certain views in certain ways, others might come to decide to zoom in a footnote. A reader needs also to bear in mind that collective editions sometimes exclude, by accident or not, literary voices of great importance.

As a researcher, I find all these cultural/ideological constructions of the literary field interesting and useful. Anthologies or any kind of collective editions, organized within a cultural context, a context we should learn to read a well, tell us more about the identity of the anthologists/editors and less about the poets.

Lately there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this strong civic awareness to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Poetry is an abstract word with a long history. Thus one may refer to a variety of ‘poetic’ experiences. I am not sure if poetic productivity is causatively connected with civic awareness. Maybe artists and poets have a strong need to communicate instantly. Maybe it is due to an extroverted performative ‘ethos’ of a multi-era; the notion of the secluded poet sitting at his or her desk is not that appealing anymore (this doesn’t mean that extroverted acts are ‘revolutionary’ or effective by themselves though). Maybe this is a reaction to the fact that a lot of books are being published and also easily forgotten; nobody reads them (despite ‘successful’ posts on social media). Maybe it is a sign of a change of the notion of poetry, a combination of arts that was once split, who knows?

However, it is important to realize that there are essential differences in each form according to their purpose; spoken poetry, for example, has a different structure, and is created to be oral. Read and listen to Kate Tempest’s poems, for example. On the other hand, there is poetry that was created mainly to be read, to speak to readers.

I think that to envision or expect a radical and fast metamorphosis through poetry is simplistic. Poetry though helps us expose or be exposed to the serious and sometimes playful complexity of our ‘realities’.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE