Elena Penga is one of Greece’s most dynamic and most produced playwrights. She also writes fiction and directs for the stage. In 2012, she received the prestigious Ourani award of the Greek Academy of Letters for her book of prose poems Tight Belts And Other Skin (Agra Publications). Her short story The Untrodden was official entry for Greece in Best European Fiction 2017, published by Dalkey Archive Press, U.S.A and her prose poems have been included in Austerity Measures, New Greek Poetry, published by Penguin and The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem.

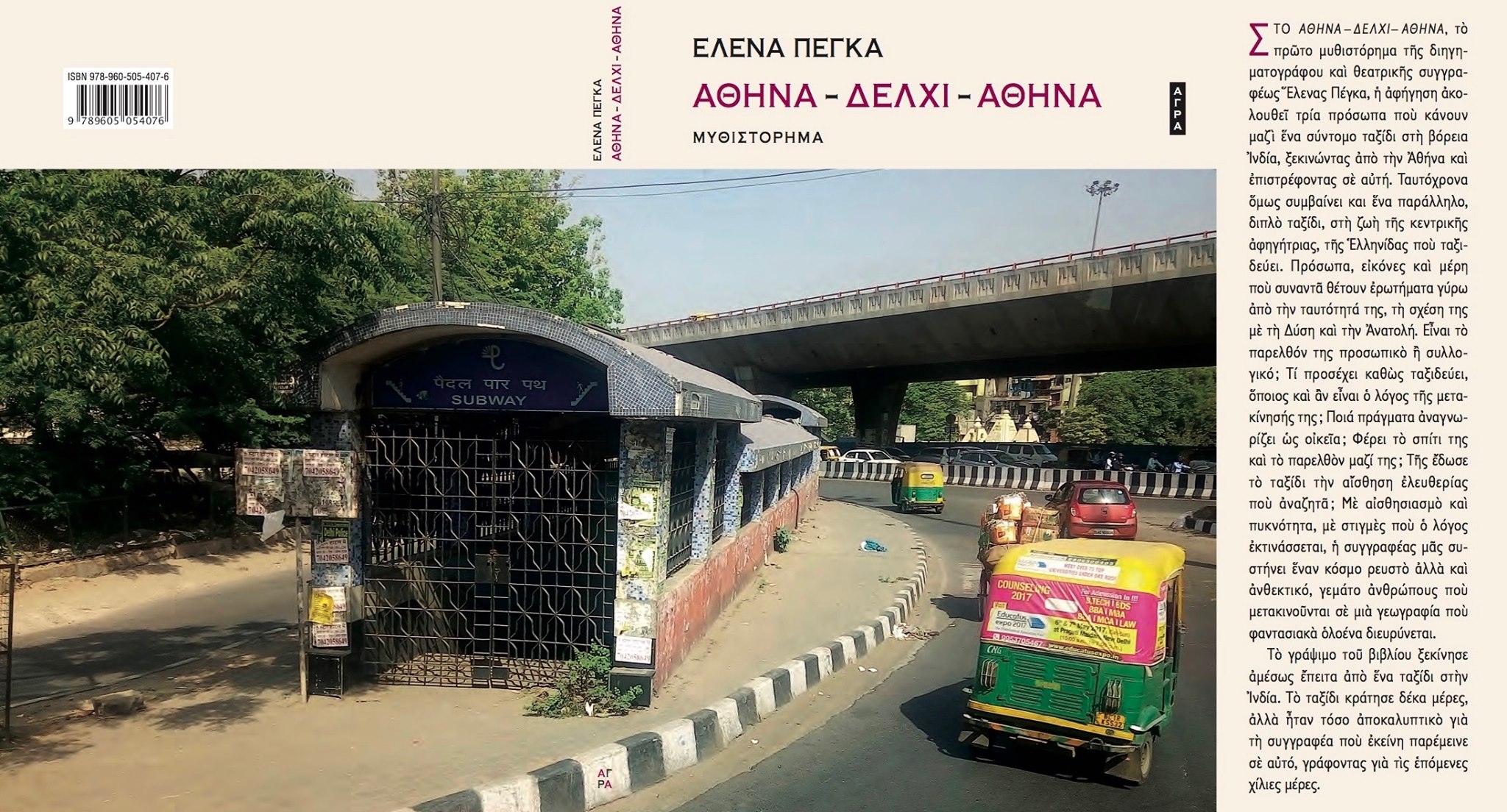

She has written a novel, three books of short fiction and nine books of plays plus her work has been translated in English, German, Spanish, French, Italian, Swedish, Dutch. Her debut novel: Athens-Delhi-Athens, published by Agra Publications, in 2019, has received very warm reviews.

A playwright, poet, fiction writer and stage director. Where do all these attributes meet? What is that binds them together? Would it be plausible to talk about communicating vessels?

Yes, in my work each medium informs the other. My background as a theater practitioner has shaped the way I see and the way I describe what I see. I see the dynamics between people in a scene, I hear the dialogue and try to decipher the hidden content, I am curious about what is not spoken and fascinated by the body and body language. The art of a stage director is a lot about interpreting a text and communicating it to the actors, collaborators and audience. As a fiction writer, I often find myself in a similar place, as I am trying to interpret a situation, a certain kind of reality, a kind of beauty or a kind of ugliness, I am exploring for myself and my reader.

Your work largely focuses on issues of human existence, aiming to explore the metaphysical and philosophical aspects that present themselves in the lives of ordinary people. Which are the main themes your writings delve into? Are there recurrent points of reference in your work?

Yes, my work focuses on issues of human existence and the lives of people. I often find myself attracted to extraordinary characters, heroes, villains, and less so on ordinary people. Or I might focus on ordinary people in moments of crisis. But, I’m not comfortable with the term ordinary. Theme is important. I have written about taboos. In my recent play Pornstar – The Invisible Industry of Sex, I wanted to speak about porn through people who are part of or very near the industry. I wanted to speak about it with liberties, not as a documentarist. I have also written Narcissus, set in a contemporary gym, in the locker room, where men change and shower. I wanted to speak about male narcissism and ask questions on how narcissism shapes male behaviour and society. I have also written Woman and Wolf, a play about a woman, who wants to live a wild, animal life, in order to feel free, because she cannot feel free in her successful career, her marriage and urban life style. What do we do with our body and our life, what others do with our body and our life, how historical forces shape us, and whether art has the power to change restricted mind-sets and lives, these are recurrent themes.

Your work constitutes a successful example of experimentation away from conventional forms. What purpose does this experimentation serve? In this respect, what role does language play in your writings?

I find the need for experimentation essential in making new work and finding one’s voice and style. Again, for me, experimentation serves the purpose of opening up different ways of seeing and perceiving, of pushing the boundaries. I find it freeing, surprising, fun. It may not always work well, but when it does, it can be refreshing. I mostly experiment with form. I do not really experiment with language as much as other writers have done in the past. My recent novel Athens-Delhi-Athens is a cross between memoir, travelogue, fantasy. A journey to India three people take became in writing very many small chapters juxtaposing Delhi to Athens, containing scenes and observations, memories, personal stories, the stories of people they meet, the stories of people I imagined they have met. To the question: what role does language play in my writings, what I can say is that my writings are not about language. I am more interested in other ways of seeing what there is.

The human body in its personal, existential, social and political dimension seems to be of great interest in your work. Which role are the body mind and senses called to play, especially in times of multi-faceted crisis? How could self-awareness be achieved against such adverse conditions?

During these times of multi-faceted crisis, it is very easy to lose ourselves, to be swallowed up by the news, the reports, the fear, the danger, the shock. Some time ago, just as lockdown measures eased, I was talking to an artist friend. She told me: “I urgently need to self-isolate, to be by myself, in order to find myself again, but this need is so strange after so many months of lockdown, spending time behind walls.” I really don’t know how self-awareness can be achieved against such adverse conditions. I really don’t know how art can be made against such adverse conditions. Perhaps, this is a good time for social movements like “metoo” and “blacklivesmatter”. It is a time to stick together and to take care of the environment we live in and do justice.

And more generally, how is literature related to the world it inhabits?

The grace and beauty of literature can help, can educate, can inspire, can move, can elevate, can console. If only people read, as much as they look at their screens.

How would you comment on current literary and theatrical production in Greece? Could art offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Greece is a small country with a very long history in the letters and in theater. I feel that the shadow of all these amazing dead poets, the tragedians, the lyric poets, the thinkers, falls heavily on current culture and takes precedence over new work. At the same time, we need to honor the living artists more, get to know them better. Yes, art does offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities. My novel Athens-Delhi-Athens ends with the image of a woman finding freedom in a very foreign environment. What often seems foreign, unknown and threatening might not be so.

How do Greek writers converse with world literature? Where does the local/national meet the global?

Greek writers converse with world literature when their work is translated and published (or performed) abroad. If this does not happen, they remain local/national.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE