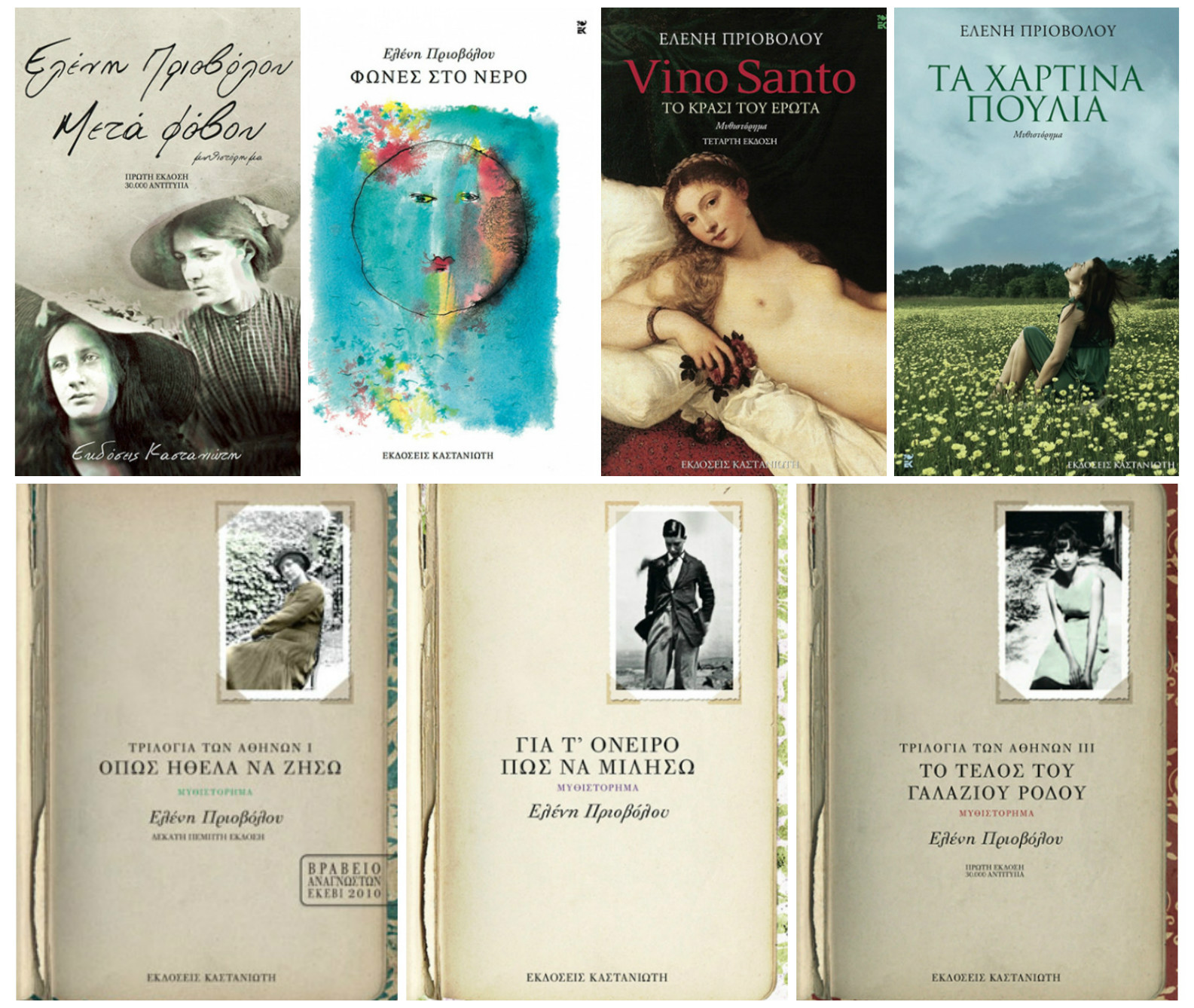

Eleni Priovolou was born in Aggelokastro, Aetolia and lives in Athens. She studied political sciences at Panteion University. She has written twenty books for children and teenagers and seven novels: Μετά φόβου [With fear] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2016), Φωνές στο νερό [Voices in the water] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2015), Vino Santo (Kastaniotis Editions, 2014), Όπως ήθελα να ζήσω [As I wanted to live] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2014), To τέλος του γαλάζιου ρόδου [The end of the blue rose] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2014), Για τ’ όνειρο πώς να μιλήσω [Hοw could I talk about the dream] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2012) and Tα χάρτινα πουλιά [Paper Birds] (Kastaniotis Editions, 2011). Her novel Όπως ήθελα να ζήσω received the Readers’ Award of the National Book Centre of Greece (EKEBI) in 2010. Το σύνθημα (2009) received the Literary Book Award for older children of the Greek literary journal Διαβάζω.

Eleni Priovolou spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest novel Μετά φόβου, which tells the story of two women set in the turbulent times of World War I and the subsequent National Schism in Greece. She talks about how challenging it is to write a historical novel, noting that “the absence of true democracy, the transformation of the citizen to a customer, and the dependency on financial elites has led the country to a dead end”.

Asked about the importance of language in the literary re-creation of a specific era, she notes that “language isn’t something static and fixed, but something flexible and developing”, and that she always “uses it in conjunction with its ancient past and cultural heritage”. She observes that “art is by its nature anti-systemic” and that “the art of writing is a political act”, while she concludes that “the fear and silence of a uniform mass of people in motion is [her] greatest fear for the future”.

Your latest novel Μετά φόβου [With fear] was recently published and has already received rave reviews. Tell us a few things about the book.

Μετά φόβου is based on the three quotes written before each chapter. The first one is a quote from Aeschylus’ Eumenides which means “Remember, don’t let fear go to your head” [«Μέμνησο, μηφόβος σε νικάτω φρένας»]; the second quote is based on the lyrics of the poet Manolis Anagnostakis “Love is a fear th at unites us with others”; the third and final quote is based on the lyrics of Yiannis Ritsos “Don’t be afraid of them. They count on your fear”.

Our main character, Aristi Vorria, fights through fear and guilt to win her freedom as a human being and as a woman. She doesn’t abide by the rules and suggestions of others and constantly goes through fire and water against all kinds of power and authority. The path she has chosen is beyond reach, as is freedom. Our second character, Dialechti, chooses to be shielded insafety and settles to life of quiet persistence. In the background of these stories there lie the tragic historical moments of World War I and Greece’s National Schism.

The ‘Trilogy of Athens’ [Όπως ήθελα να ζήσω, Για τ’ όνειρο πώς να μιλήσω, Το τέλος του γαλάζιου ρόδου] delves into the political malaise that has been afflicting our country from the 19th century onwards. How challenging is to write a historical novel? What would you say “is to blame” for this ‘Greek malaise’?

I would say that all of my books are politically conscious because I am a politically conscious citizen; this has led to my early literary expression. Writing a historical novel is particularly difficult, especially when the researcher is constantly looking for the secrets and lies hidden between the lines of history, when he doesn’t settle for the obvious truth and doesn’t compromise with the historical facts that serve the purposes of a particular dominant ideology. Giving up one’s ideology is a difficult task, especially when the writer is confronted with facts he didn’t use to believe in and then finally has to pull the rug under his own feet. I wouldn’t call what’s happening here in Greece a ‘malaise’: I would call it misjudgment. The absence of true democracy, the transformation of the citizen to a customer, and the dependency on financial elites has led the country to a dead end.

How important is language for the literary re-creation of a specific era?

To me, language is the essence of literary creation. I sometimes dare to break syntactical rules for the sake of harmony. I am keen on recreating linguistically the different eras I am writing about, such as 19th century, interwar era etc, in the most accurate way possible, not only for the sake of accurate historical illustration but also for the preservation of words that tend to disappear from our vocabulary. In my opinion, language isn’t something static and fixed, but something flexible and developing, and I always use it in conjunction with its ancient past and cultural heritage.

You have been writing books for adults, young people and children. How are these activities combined? What differentiates them and what is the binding thread?

That’s right. I address all ages and write according to my personal expressive needs. I treat children not as a separate but an integral part of our society, a constituent subjected to the same rules and consequences as everyone else. That is why I often use fairytale symbols to talk to children about themes that are more adult. In my opinion, literature is universal. The only thing that changes is the way of writing, so that its meaning can be grasped by the young reader.

“Culture should be anti-systemic, otherwise it just serves the system’s purposes”. Could you elaborate on that?

Art is by its nature anti-systemic. It’s not very common to see artwork that glorifies authority or the system that supports it. Unless, of course, we talk about an authoritative regime where artwork is dictated by force. In that case it’s not art, but awful kitsch. Take for example Greek poetry competitions of the 19th century: If a poet wanted to win the first prize, he had to write 500 verses full of chauvinist nonsense and patriotic stupidity. This is not art. On the other hand, there is a question: Is it possible for a great artist, whose work is against all kinds of authority and power, to consort with authority representatives or supporters so that he or she can remain in the public eye? In any case, works of art provoke, criticize and clash with authority.

Would you say that art, and literature in specific, is a political act, a conscious decision to participate in social change?

To me, the art of writing is a political act. In my works, I have created the world as I would like it to be, and it is for that world that I fight for, not only for myself but for future generations, even if it seems utopian. I firmly believe that political change is up to each citizen, as long as they realize that they carry their own responsibilities in all the aspects of their lives. In my opinion, political change doesn’t come about from the top of the hierarchy but from the base, the citizens, who should be fearless and educated. The education system should nourish responsible citizens and not components of manufacturing machinery, incubated people who think and act unvaryingly. The fear and silence of a uniform mass of people in motion is my greatest fear for the future.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE