Eugene Trivizas is one of Greece’s leading writers for children. Although educated in law and a specialist in criminal law and comparative criminology, he has published more than 120 children’s books. He has written short stories, fairy tales, picture books, novels, poems, television series, songs, plays and even opera librettos for children. Humor, subversiveness, a multilevel complexity and the unexpected transformations of classic stories and images are the key elements of his work. He has received multiple national and international prizes and awards, including honorary distinctions by the US Library of Congress and the Polish Center for Youth, while much of his work has been adapted for stage, screen and radio.

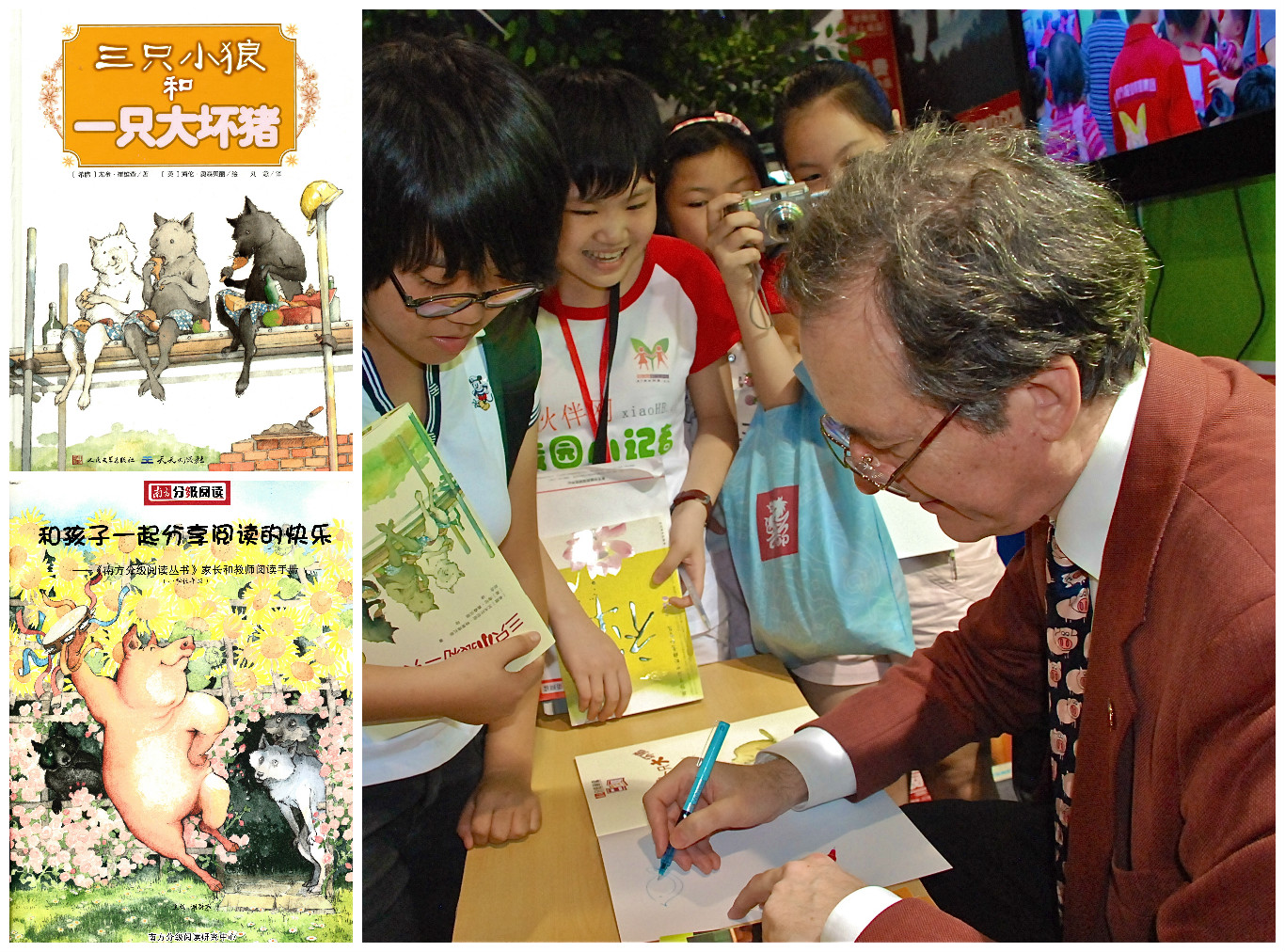

His first book for children published in the English language was The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury and published by Heinemann in 1993. The Economist wrote about this book that “only the most talented of writers can tamper with a classic nursery tale and produce something almost as amusing and thought-provoking as the original“. The book reached the second place in the American best seller list for picture books and has won many distinctions. His books have been translated in more than fifteen languages. His book Emily & the Cherry Stalk was voted best preschool e-book of the year 2015 by the prestigious Kidscreen Awards.

Eugene Trivizas spoke to Reading Greece* about what drove him to writing books for children noting that his longing for a story he liked never to end became the reason why he started writing his own fairytales. He comments that “a book should have three primary goals: to entertain children, to broaden their creative horizons and to cultivate their imagination”, adding that he writes books that “both small children and mature adults will enjoy at different levels”. Asked about the way he handles the issues of war, violence, prejudice and bullying in his books, he explains that “through the use of symbols and allegories, you can talk to young children about serious, even tragic issues without traumatizing them”.

As for the Greek educational system, he stresses that “education should aim not so much to impart knowledge – given that knowledge nowadays is easily accessible – but to cultivate children’s creativity and imagination, so that this knowledge is employed in innovative ways”. He concludes that “the more difficult the social conditions, the stronger the need to envision a brighter future” and that “fairytales offer children the hope that we can defeat the dragons and the monsters that threaten and oppress us”, while they also “transmit the message that we are able to overcome the limitations of our roles, our environment and our existence”.

What drove you to writing books for children? What continues to be your driving force?

When I was young and someone read a book to me, I felt betrayed when at the end I heard “and they lived happily ever after”. The heroes may have lived happily ever after, but they had abandoned me all the same. Thus, I tried to imagine what would happen if the story went on. At times I offered first aid to the defeated dragon or I tried to discover where the eight neglected dwarf was hiding, while at others to guess what the last dream of Sleeping Beauty was right before she woke up or even to visit the shoemaker who made the boots of Puss in Boots. This longing for stories I liked to continue and never end became the reason why I started writing my own fairy tales.

I began writing my first novel The Chimney Pirates while still a child. When it was first published in sequential instalments in a children’s magazine, I received my first letter from a girl. “It’s strange”, she wrote among others, “that I feel the Chimney Pirates as my own, as if they were hidden in my imagination and they suddenly woke up…”. At a time when I had discontinued literary writing and was thinking of devoting myself entirely to criminology, this letter – which I found while rearranging some papers – induced me to continue writing books for children. The magazine page with the letter is included in the exhibition FROM FRUITOPIA TO THE ISLAND OF FIREWORKS, which has just concluded at the Michael Cacoyannis Foundation and will be transferred to the HELEXPO Thematic Park museum,THE SECRET WORDS OF EUGENE TRIVIZAS.

What makes a book attractive to such a demanding audience as children? And, in turn, what do you want to offer kids through your books?

A book should have three primary goals: to entertain children, to broaden their creative horizons and to cultivate their imagination. When I am asked why I write books for children, my response is that I don’t just write book for children but for the whole family. In other words, I try to create books that both small children and mature adults will enjoy at different levels, as it is the case for example with the classics Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, or The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupery. The concept of shared enjoyment is predominant in my literary work.

“The stereotypes of good and evil which are propagated through the medium of children’s books are often not only wrong, but even dangerous. They lay the foundations for prejudice against minorities, as well as breeding many other social ills”. How do you handle the issues of war,violence, prejudice and bullying in your books?

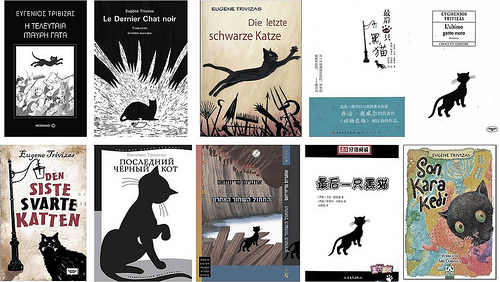

I believe that, through the use of symbols and allegories, you can talk to young children about serious, even tragic issues without traumatizing them. For instance, the issue of racist genocide is tackled in The Last Black Cat. In the book members of a secret sect are convinced that black cats bring about bad luck and they decide to exterminate them, supported by business circles active in the trade of cat traps as well as by political leaders who find in black cats convenient scapegoats for their disastrous policies. Within a short period of time, the ruthless persecutors have almost achieved their goal. Only one black cat remains alive. The members of the sect are determined to track this cat down and kill it! My anti-war book series titled Bang-Bang- Bing-A-Bong (The War of the Lost Slipper, The War of the Oufrons and the Tzoufrons, The Alphabet Soup War, The Whale that Eats War) touches upon the issue of war crimes, while the problem of bullying is tackled in my book The Rabbit’s Mandolin.

Criminology and children’s writing seem quite distinct fields of interest. Is curiosity what bringsthem together?

Both the criminologist and the fairy-tale creator observe what for many may go unnoticed. For both the seemingly trivial could be be critical. An orange juice straw, an ice cream stick, a confectionery wrapping, a burnt match, a milk bottle top, may hide a clue for the solution of an atrocious crime or the beginning a charming fairy tale. Additionally, many of the issues modern criminology deals with, such as guilt, transgression and punishment offer rich material for my books: the trial by landowners of a scarecrow that dreams of flying and his conviction for attempted violation of the law of gravity in The Scarecrow’s Dream, little Amy’s unbearable remorse in Amy and the Banana Skin, the outrageous methods of execution of convicts in The Executioner’s Frying Pan, or the unexpected encounter between a burglar and a miser inside the safest safe of the world in The Baron’s Golden Turtles.

What about the Greek educational system? What reforms are in your opinion needed in order to make schoolbooks and school courses attractive to children?

Every time I visit schools, I am impressed by the boundless imagination and the infinite creativity of preschoolers. A few years later, I see the same kids behaving like robots. Tired and stressed, they have already lost this freshness of approach, this magic spark. We teach them how to serve reality instead of how to shape it. Education should aim not so much to impart knowledge – given that knowledge nowadays is easily accessible – but to cultivate children’s creativity and imagination, so that this knowledge is employed in innovative ways.

In November 2015, astrophysicist Dimitris Nanopoulos invited me to take part in the presentation of his autobiographical work titled Στον τρίτο βράχο από τον ήλιο [Third rock from the sun]. In the book, he refers to how repelled he was by the way the subject of Physics was presented in school books and cites a quote by Manos Hatzidakis on how he envisioned the education of the future, “an education that propels towards a flying leap to the stars”. This is true not just for Physics books. Many school books are so boring, tiresome and tedious that instead of stimulating students, they drive them away. Instead of a “leap to the stars”, they lead to a massive leap away from books.To make matters worse, school books cause so much discomfort to kids that for the rest of their lives they loathe everything printed (with the possible exception of chequebooks).

School books could well become much more attractive were the learning process to be enriched with humor and imagination. For instance, a simple math exercises like “One kilo of potatoes costs two euros, how much do twenty kilos cost?” could be formulated in a different way such as “When Pinocchio tells a lie, his nose grows by two inches. How long will Pinocchio’s nose be if he tells twenty lies?” The exercise remains essentially the same, yet the way it is formulated stimulates the child’s attention much more effectively.

“The ability to imagine the nonexistent, the process of creating in our minds images or concepts beyond empirical reality is directly related to scientific thought, technological progress and economic prosperity”. What role does imagination play especially in times of crisis? Do books constitute an effective means to talk to children about the crisis?

The more difficult the social conditions, the stronger the need to envision a brighter future. Fairy tales offer children the hope that we can defeat the dragons and the monsters that threaten and oppress us. They also transmit the message that we are able to overcome the limitations of our roles, our environment and our existence. In my play The Scarecrow’s Dream, a scarcow learns how to fly, in the novel A Girl and a Snowman a snowman detemined never to melt, sets out on a long dangerous journey to the north pole and in my opera libretto The Chessboard Fugitives a pawn, a wooden horse dreams of fleeing the chessboard and gallop on a meadow of four-leaf clovers .

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE