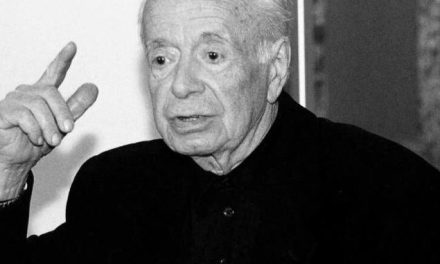

Evriviadis Sofos was born and raised in Mytilene, Greece. He studied Translation and Interpretation at the European Educational Group College (EEO) and Spanish Literature at the University of Granada. He continued with postgraduate studies in Literary Theory and Comparative Literature at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He is a teacher of Spanish language and translator of Spanish and Catalan literature.

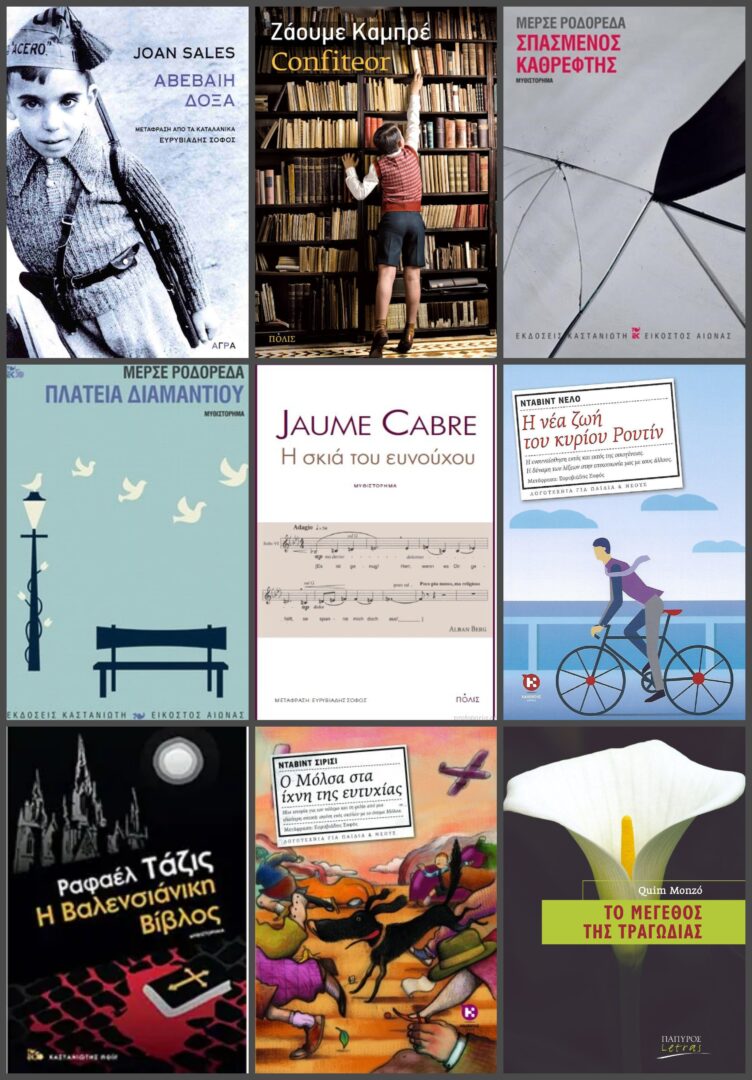

As a translator he started by translating short stories for literary magazines and then worked with various publishing houses. In 2017 he received the Greek State Prize for Literary Translation of Foreign Literature into Greek for his translation from Catalan of Jaume Cabré’s book Jo confesso (published in Greek by Polis Books, Confiteor). In 2024, he received the 4th LEA Literary Translation Award for the novel Incerta Gloria by the Catalan Joan Sales (published in Greek by Agra Editions).

Υοu have translated major Spanish writers in Greek, among which Jaume Cabré, Joan Sales, Irene Solà, Mercé Rodoreda. Which have been the major challenges you have been faced so far translating Spanish literature?

I have translated authors who come from Spain but write in Catalan, a language that differs from Spanish. They carry this different identity in their texts and almost all of them write, in one way or another, about it. Catalonia as an inspiration, as a field of action, of everyday life. It has been a challenge to try to make this different Catalan identity understandable through my translations. I also faced challenges when I had to find correspondences at a linguistic level, when I had to explain, resort to footnotes, render lyrical elements, sometimes successfully while at others awkwardly.

What is that makes Spanish literature appealing to Greek readers? In turn, does Greek literature have the potential to attract audiences beyond national borders?

I reckon that the literature written in the Iberian Peninsula, mainly in Spanish, within the wider framework of the Mediterranean countries, is a familiar world for Greeks. We could talk about the same familiarity that we feel when we read texts by Turkish, Albanian, Israeli writers. We share a particular geographical space that over the centuries has operated, more or less, by similar rules. Greek literature can reach new readerships; what it needs is substantial promotion, a dynamic presence at foreign book fairs with innovative proposals for all those young writers who write in Greek. This could become a reality following the implementation of a specific strategy.

“What I’m most interested in is finding a balance between the original text and the Greek language. […] My concern is to respect the author’s choices, which I believe should be attributed as much as possible to the language in which they are translated”. Tell us more.

This quote comes from an earlier interview, I still think the same. I am interested in respecting the original text, studying the author’s choices, what words they used, the rhythm they followed, their repetitions and finding the equivalent, if any, in Greek. I think it is important that there is some kind of balance between the translation and the original, that the Greek text does not stray from the context of the original, whatever its identity and quality. We cannot improve nor degrade. We can deliver. We proceed as the original text dictates.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

I think it is necessary for the translator to be familiar with the foreign language they are translating into Greek. In the past this was not necessary, but our era requires a substantial knowledge of the reality of the language used in the text, as well as a continuous update about all the changes that the foreign language undergoes. Unlike in the past, languages are now organisms that mutate much more rapidly. The internet provides knowledge, but in many cases, it is not enough. Personal experience is required.

In case we are talking about a language with peculiarities, the translator would be well advised to respect and highlight them because they are obviously present in the text and perform a specific task. The translator has a responsibility to recognise the original text and try to create something similar, but unfortunately this is not always possible. In such a case, it would be advisable to opt for a more neutral version that does not alter the original and allows for flexibility, producing a functional result.

Within this framework, unethical identifies with non-functional.

Despite their arduous and pivotal work, translators usually remain invisible: their names are often not even mentioned, while they are ignored by critics and readers. What could be done to bring translators to the forefront?

Translators could be given space, a platform to speak about their work, if they wish to do so. The course of the book that has been translated should be accompanied by the name of the translator. Without translation, there is no world literature; texts could not travel. Technology is making huge strides, there is talk of artificial intelligence, yet the literary text contains nuances that cannot be understood by a machine. Whole texts are translated by machine translators, but who will be responsible for making them readable?

Could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

This is already happening, i.e. texts travel from country to country, enabling part of the population to have access not only to the literary wealth and potential of each country but also to discover paths of communication that strengthen contact between different countries. The customs, habits, geography, food and people of a country are discussed and this is a reason for some to travel and discover more of its aspects.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE