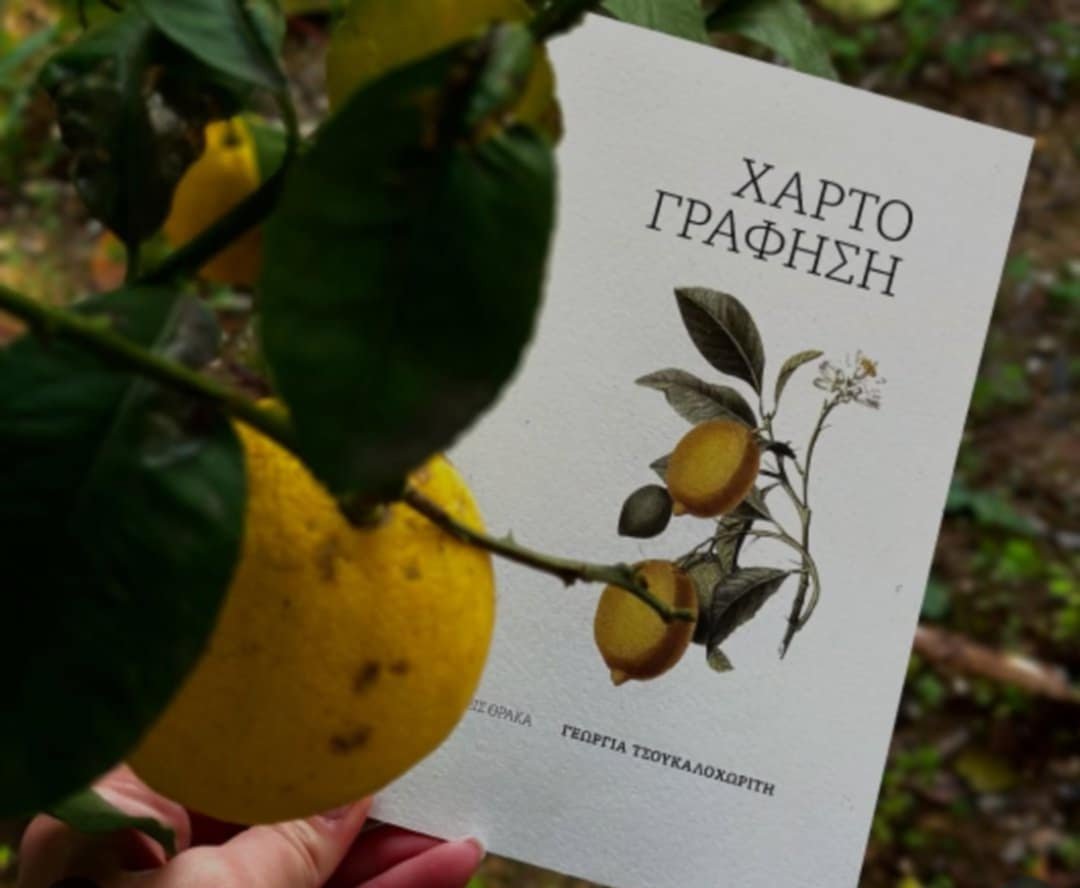

Georgia Tsoukalochoriti was born in Athens in 1994 and grew up in Athens and Vatera, Lesvos. She studied English Literature at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Alexandria Publications published two collections of her short stories (The Feathers of the Rooster, 2018, and The Void, 2022). Her first poetry collection titled Charting was published by Thraka in 2024.

© Dimitris Polydoropoulos

Your first poetic venture Χαρτογράφηση [Charting] was recently published by Thraka. Tell us a few things about the book. What does “charting” refer to?

This charting symbolizes my journey in trying to understand my life so far. From a young age, I became aware of how trauma has shaped my immediate and extended family from one generation to the next. Growing up, I always loved dancing and movement in general, and I began noticing how back pain or knee pain seemed almost hereditary. At first, this connection between psychological and physical inheritance scared me. I have worked –and I still am working- on breaking this cycle of both emotional and physical pain. But over time, I found this realization to be inspiring—I saw that I could transform it into something beautiful.

The book seems to offer an insight into personal experiences. Where do these individual micro-stories meet the History of the world?

Yes, the book is based on personal experiences, but my goal was to create something more inclusive. I wanted these microstories to resonate with people’s experiences, from everyday moments to heartbreaking events to philosophical reflections. To be honest, that is the main reason I write—I feel a deep need to communicate through art.

Τhe poems seem to delineate the process of a woman coming of age in an unfriendly world. Could gender and its political aspects offer a revolutionary potential in literature?

My bachelor’s degree was in English Language and Literature, and during our Shakespeare class, our professor explained that writers of that time often presented their ideas indirectly. They would embed a play within a play or use dreams—something removed from reality—as a way to criticize the king or other authorities, as openly expressing dissent through art was highly dangerous. Art has always been revolutionary, and it should continue to be. Of course, this must be done skillfully—literature shouldn’t become a vehicle for propaganda. But if literature, and art in general, do not challenge our thinking and inspire us beyond systematic conventionality, I honestly don’t know what will.

© Elli Maria Mouchopoulou

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

I grew up in a family where language was very important. My parents would always admire a book for its linguistic style and would often correct any grammatical mistakes I made. Even though I hated being corrected, this focus on language had an impact on me. When I was six or seven, I started communicating in English because of my Greek-American friends, and that literally opened a whole new world for me. I began observing both languages as closely as I could. Of course, growing up on the island of Lesvos also had a significant influence on me, as the local dialect includes many Turkish words, which my aunt frequently used, and still does. Thus, I can say that when writing, language and the aesthetic side of it, is my main concern.

You have also published two short stories collections. Does short form seem more appropriate to depict the contemporary fragmented world?

For sure, the short form does reflect the fragmented society we live in, and honestly, I don’t want to stand against that in a judgmental way. I mean, it is what it is, and more than that, it’s always interesting to observe how the way of life influences art. However, the short form definitely feels appropriate for my fragmented attention, if I may say so. I have always struggled with focus and concentration, and honestly, if my parents hadn’t been teachers and hadn’t helped me the way they did, I don’t think I would have made it to university. So, embracing short forms for me means embracing a part of my identity that I’ve always tried to change and hide.

How do young writers relate to the world of literature? Where does the local and the national meet the global and the universal?

I am always a little extra cautious when answering questions about our generation, especially about young writers. On one hand, I feel that I understand how other writers feel since I’ve met several of them, since I love socializing. On the other hand, though, I believe that many aspects that will define us as a generation in the future are still being shaped. For sure, societal factors affect us all as writers, and as time goes by, I think the national and global can intersect more easily. The web and all its accompanying changes have influenced us as a generation, and it will continue to do so. The pain that our great-grandparents experienced coming here from Asia Minor can’t have been very different from the pain that Palestinians feel today. The easy access to information can have several negative aspects, but it can also empower our generation’s universal narratives.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE