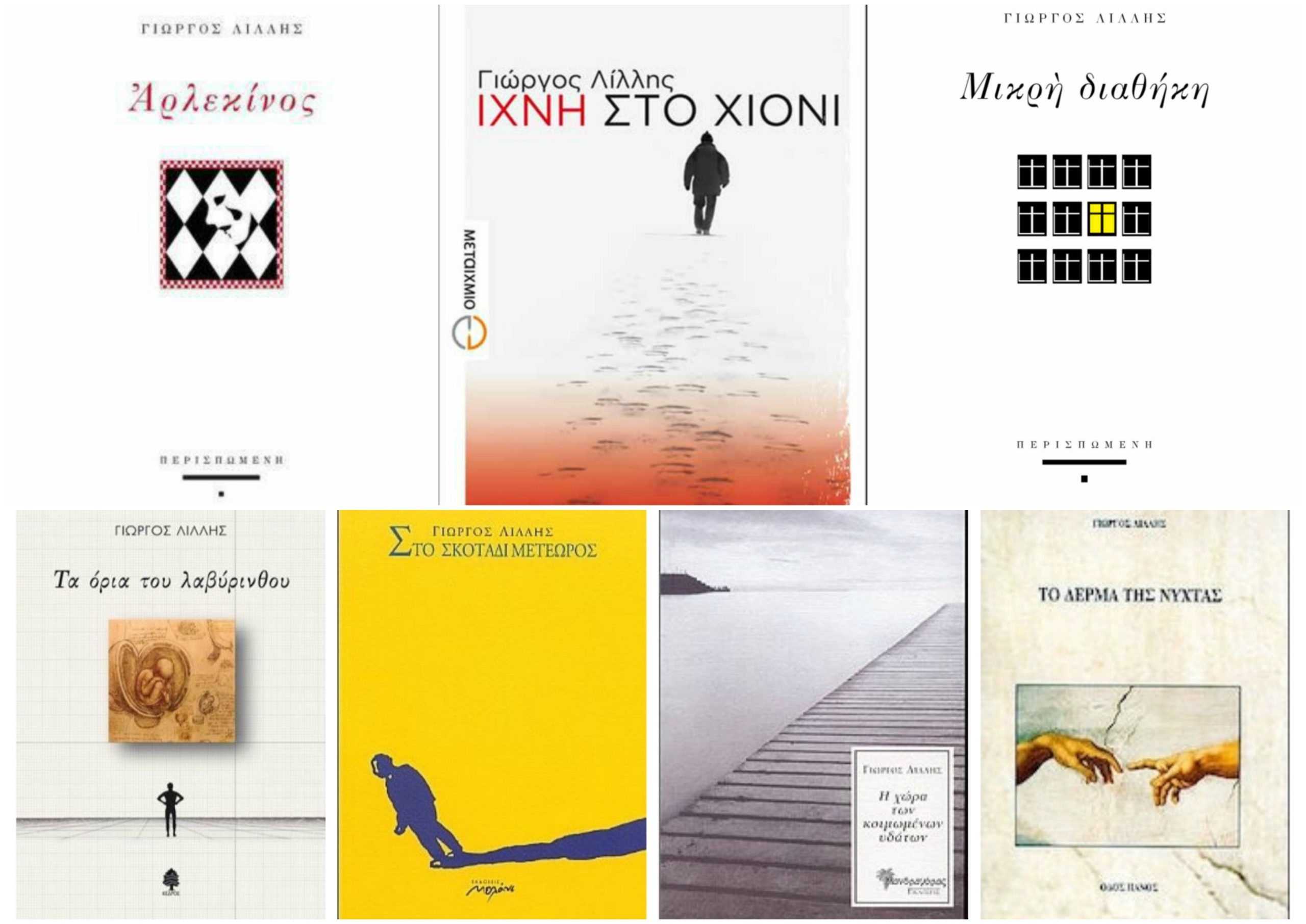

Giorgos Lillis was born in Bilefield, Germany in 1974, and raised in Athens. In 1996 he went back to Bilefield where he still lives and works. In 1999 he published his first poetry collection Το δέρμα της νύχτας [Τhe skin of night] (Odos Panos editions). Since then he has published six more poetry collections: H χώρα των κοιμώμενων υδάτων [Τhe country of the sleeping waters] (Mandragoras ed., 2001), Στο σκοτάδι μετέωρος [Floating in the Darkness] (Melani Books, 2003), Τα όρια του λαβύρινθου [Bounds of the Labyrinth] (Kedros Publishers, 2008), Μικρή διαθήκη [Small Testament] (Perispomeni Publications, 2012), Αρλεκίνος [Harlequin] (Perispomeni Publications, 2015) and O άνθρωπος τανκ [Τhe tank man] (Thraca Books, 2017); a novel, Ίχνη στο χιόνι [Τraces on the snow] (Metaixmio ed., 2012); and a children’s book for his newborn daughter.

He has translated in Greek Indian poets, as well as the German poet Durs Grünbein. His book reviews and essays have been published in several newspapers and magazines. His poems have been translated in English, French, Spanish and Italian, while his poetry collections Floating in the Darkness, Bounds of the Labyrinth and Small Testament have been published in German.

Giorgos Lillis spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes his poetry touches upon noting that what remains the same in his poetry is his “anguish to find a way out of all those things that deprive us of freedom”, “the man who confronts himself and the world”. He explains that “there should be no ‘musts’ in poetry” since “its purpose is to pose questions and not to offer answers”, and adds that “a politically militant poetry may lose its importance because of its ephemeral character”.

Asked about the new generation of Greek writers, he comments that “nowadays we can no longer speak of a national literature or a specific generation but of a group of people, who, despite their quite distinct traits, have left their mark with multiculturalism as their main feature, safeguarding at the same time their cultural identity”. He concludes that “only when you have really understood the text, only when you have loved and made the text yours can you translate poetry to another language”.

From The skin of night in 1999 to The tank man in 2017 what changed and what remained the same? What are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

What has actually changed is that I am now much more self-aware. I remember twenty years ago, when I wrote those first poems, I hadn’t yet understood that poetry is a demanding art. I was overwhelmed with an enthusiasm that led me to writing without even the slightest self-reflection. That certainly changed over time. I may lack that first enthusiasm, yet this helped me distance myself and see my poems more critically. What remains the same, however, in my poetry is my anguish to find a way out of all those things that deprive us of freedom. It’s the man who seeks the truth, the man who is no longer close-minded, the man who confronts himself and the world.

In your latest poetry collection The tank man there are concrete references to the current socio-political conditions. Can poetry act as a political paradigm? Is it in the capacity of poetry to be ‘politically militant’?

It wouldn’t be right to use labels for an art that is famous for not getting into molds. A politically militant poetry may lose its importance because of its ephemeral character. I believe there should be no ‘musts’ in poetry. Its purpose is to pose questions and not to offer answers. As for the poems of my latest book, they may have a socio-political tone, yet their starting point is man himself. The poems reflect my own concerns and worries. And I come face to face with myself. I have deliberately put myself under scrutiny. And I have been ruthless. If you are not eager to question your ego, then nothing can be done. You will remain static. And I definitely don’t want that. I prefer to leave myself exposed rather than feeding myself with illusions.

“When I write poetry, I have no specific plan, with my subconscious taking the lead; unlike when Iwrite a novel, which requires a plot and characters”. What made you turn to novels as a means of literary expression? What differentiates the two? Is there a binding thread?

When I write poetry, indeed I have no specific plan. I just go with the flow. It’s afterwards that I work on the poems. This editing is quite important so that you remove empty words and the essence remains. I have written poems which I had been working on for years and now that I see them published, I am not at all satisfied. As for prose, things are much more clear-cut. You have a specific theme, characters, a specific frame on which you depend to move forward. I don’t mean to say that it’s easy to write prose, yet from personal experience I reckon that poetry is much more demanding. I turned to prose once since the story I wanted to narrate couldn’t be told in verse.

Your novel Traces on the snow refers to the Greek Civil War, a historical period that has appeared in many Greek novels in recent years. What motivated you to delve into such a thorny issue? Do we think that we are ready, as a people, to look back to those events with sobriety or it is still early?

I came to write about the Civil War quite by chance. The story I wrote about, the story of young Pericles, is real. In 1992, during one of my trips to mountainous Aetolia, I met Pericles, the hero of my novel. I stayed at his house and as we were sitting by the fireplace, he told me that his parents were murdered by the National Army and that he escaped with the rebels to the mountains of Evritania. That’s when everything started. I didn’t know then that I would ever write a novel because of that narration. The idea came much later, in 2009. Although my generation didn’t’ witness the events, it has the advantage of distance. As far as I am concerned, there are no good or bad guys. Actions speak for themselves. And they are well documented by historians. The Civil War has certainly been the gloomiest period in Greek history and this has nothing to do with who is to blame. We are talking about lives that were lost, people who were hunted and lost their properties and their homes, people who were exiled. And this is something we can not ignore.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek writers is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. What is it that makes a national literature appealing to a foreign audience? And to what extent does the new generation of Greek writers incorporate foreign influences in their work?

Nowadays that the internet plays a primary role in our lives, it’s much easier to get acquainted with literature written outside our national borders. There are numerous writers of my generation that not only know more than one language, but also live permanently abroad, as is my case, which has exerted a great influence on their writing. I am really interested in reading what poets my age get to write in Germany, the UK or the USA. This is definitely not something new. Let’s take the poets of the 1930s, for instance, who had delved into foreign poetry and were eager to admit their influences. Yet, they didn’t just imitate or reproduce those writings, but rather enriched them with their personal poetic vision. Nowadays, we can no longer speak of a national literature or a specific generation, but of a group of people, who, despite their quite distinct traits, have left their mark with multiculturalism as their main feature, safeguarding at the same time their cultural identity.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of a translator lie?

A translator rewrites from scratch the book he is called to translate. It’s definitely not an easy task to transfer the particularities of a language to another as you mention. You need that, even minor, intervention which will make the text sound familiar to the language it is translated to. What a translator actually does is enable communication between two languages. You need to be humble so that you don’t take too much freedom and the original meaning is lost. Especially when translating poetry, only when you have really understood the text, only when you have loved and made the text yours can you translate it to another language.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE