Giota Tachtara was born in Greece, studied Political Science at the University of Athens, Journalism at UCLA, and Content Writing at Cornell. Since 2002, she has been writing, editing and translating for women’s magazines, websites and newspapers, interviewing artists, designers and a wide array of cultural workers and covering yearly events like the New York Fashion Week and the MET Gala for Vogue Greece. Her opinion columns, essays and short stories have been featured in major publications in Greece, USA, Cyprus, and Turkey.

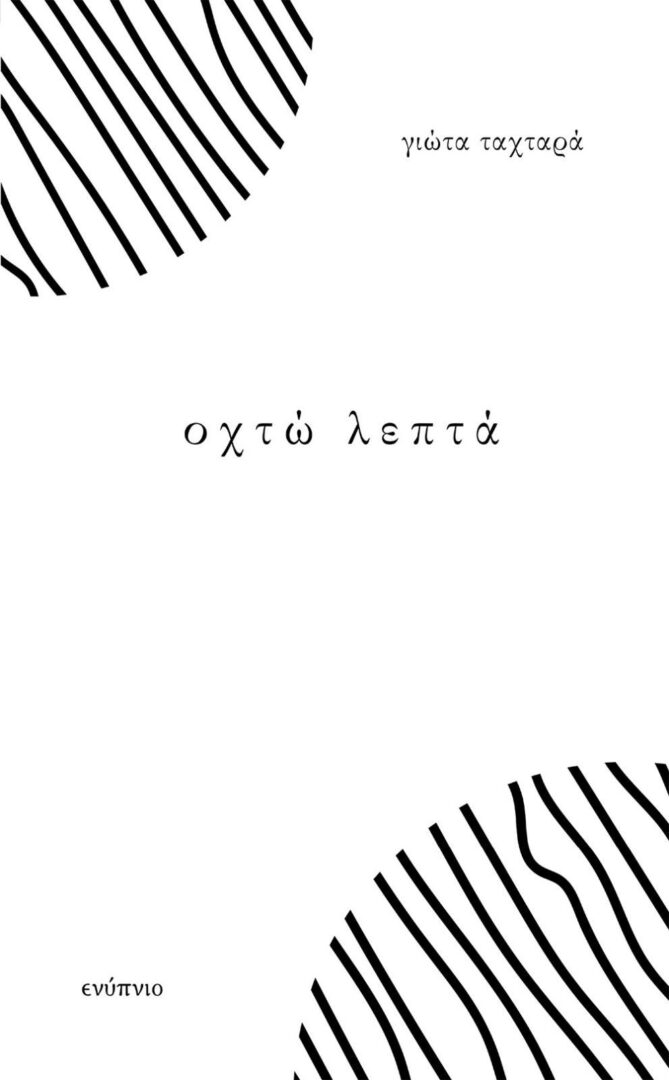

For more than ten years she has moved around between Ann Arbor, Princeton, Athens and Istanbul with her partner and their two sons, leaving a trail of Lego bricks all the way back to Ann Arbor, where they finally settled in 2020 for good. She works as a Communications & Marketing Specialist at the University of Michigan, maintains her monthly opinion column “Viewpoint” at Vogue and just published her first book of fiction Οχτώ Λεπτά [Eight Minutes].

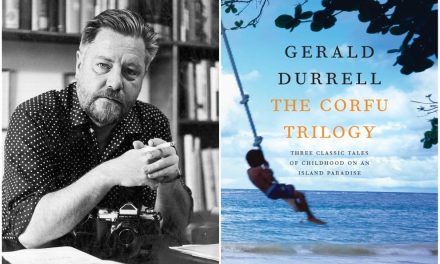

Your first book of fiction Οχτώ Λεπτά [Eight Minutes] was recently published by Enypnio. Tell us a few things about the book and its title.

It’s a novella in first-person narrative that constantly hovers between the past and the present, here and there (the US and Greece), the self we remember before and after big life events. The narrator embarks on a vast journey sharing memories from her childhood in Greece, to adolescence struggles, to her move to Los Angeles, the return to Athens, falling in love, working in media, navigating motherhood, finding and losing friends. The narrative flows somewhat associatively (συνειρμικά), like a conversation with friends where one word triggers another, unfolding the entire story, mostly around tables where everyone gathers, because the need to get together is a survival mechanism, trying to find where they belong. The sense of being unsettled or not-belonging is very intense, even during the early years of childhood, and it gets worse with the tension of language, cultural differences, and a young woman’s effort to find where she fits in today.

The title, Eight Minutes, comes from a fleeting conversation at a chaotic party in Los Angeles, when someone shares one of those bits of scientific trivia we love to dole out with cocktail in hand, claiming that if the sun explodes now it will take us eight minutes to realize it here on earth. And everyone in the room has to come to terms with the idea that we’re constantly a few minutes away from death without even knowing it. Of course, if you try this party trick to a group of people in Ann Arbor, you’ll probably find least one person who literally has a PhD on the subject, so it’s a bit simplified and definitely more philosophical and existential than scientific.

“Athens was the real family we had left and the only family we missed. But I couldn’t admit it..”. How are the notions of homeland and ‘nostos’ imprinted in your writings?

Leaving your homeland is a life-altering experience that shakes you to your core. In all the excitement of planning you don’t realize how much of your idea of self is based on language, cultural norms, and everyday life in the city you grew up in. When you take away the familiar, the comfortable, the beloved, the small things that make you who you are (from the favorite coffee shop or the route to work everyday, to your closest circle of friends and family) you’re left with so little–and this is what you really pack in your luggage, this is what you hold while you wait in line at the airport’s immigration desk. In 2010 I found myself in a similar line, clutching a thick folder with paperwork and a chest x-ray and I had no idea who I was when I made it to the other side of the border. My accent transformed me immediately into the “other,” my jokes needed a whole encyclopedia of cultural references, most of my new friends struggled with similar challenges and made connections harder, and the longing to go back where everything seemed so much easier was crippling in its intensity.

I recently wrote an essay about the experience of being an immigrant in Michigan for a public humanities project of the department of Comparative Literature, and I had many women come to me afterwards and comment on this one phrase, how infantilizing it is to be a foreigner. And it’s hard for us, because empowering ourselves is a struggle to begin with, so losing all the progress we have made is deeply unsettling. When the main character of my book finds herself in a similar situation, between languages and cultures, homesick and self-conscious, she keeps thinking of her old stomping grounds with nostalgia. When I was writing, it was easy to dip into my own personal experience and get inspired by it. The character misses her city and everything she left behind, but deep down what she misses most is the solid sense of who she is, before the different sounds of words (and worlds) made everything more confusing for her. And of course, when everything falls apart, she goes back to the place she can find her footing again, she can stand on her own two feet–and that’s where the real home is.

Language plays a pivotal role, especially in short form. What role does language play in your writings?

I think what makes me love short stories and novellas so much, both as a reader and a writer, is exactly that the focus is on language. The form, the flow, making every word count, debating over a sentence with the strategic intensity of a poet. It’s like putting together a puzzle, but with some of the pieces deliberately missing and you have to rearrange everything over and over again to make sense out of it, to create the full picture.

Being a magazine writer for over 20 years now has also helped me develop this skill. I had to learn how to make an article interesting, funny, accurate, but also stay under the word limit–and keep a deadline! Language has always been a fun thing to play with, and I found the best expression of these experimentations in the short form.

“I’m lucky enough to have ‘the women in my life’ around me who have supported me for so many years and not only let me be myself, but actively create enough space for me to exist and move freely,” you said in an interview, and friendship seems to be a key issue in the book as well. How important is this bond between women both in your personal and your professional life?

Vital. Nothing in my life would have been the same without these women. All of them. Friends, mentors, cousins, fellow writers in workshops, they had different roles and I met them at different times of my life, but all of them are crucial in the narration of my life story. I’ve been mostly working in women’s and fashion magazines since 2002 and I’ve met the most charismatic, brilliant women, who supported me in very concrete ways when I needed it. It’s very easy to get a bumper sticker that says “women support women” but extremely difficult to do it, especially in the media. I‘ve had colleagues help edit my articles–on top of their workload–when I had my first baby and couldn’t get over the brain fog. I’ve had great writers sit down with patience and grace and help me find my voice. I had the encouragement of my editor-in-chief to take the final exams and graduate college when I was close to quitting–and she made sure I got paid days off to study enough. The list can go on and on. These women empowered me to stand my ground personally and professionally, navigate everyday struggles with systemic patriarchy, and not let anything stand in the way of my dreams. Their practical, emotional, mental, professional support and advocacy made me more confident to take risks, to reach for everything I ever wanted. And they get it. They get how hard it is to exist as a woman today and what a difference we can make for each other.

You have been travelling around the world, from Athens to Los Angeles, from Istanbul to Michigan. How is this constant move between countries and cultures imprinted in your viewpoint of the world? Is it too early to ask if you have already found your Ithaca?

No, I haven’t found my Ithaca yet, which is a wonderful thing, because I don’t want to stop looking for it! As every inspirational quote on tik-tok will confirm, travelling is a great way to broaden your horizons. They will also inform you that “you can only find happiness when you leave your comfort zone.” And all these are catchy and fun, but not very helpful when you need a dictionary to do laundry because every washing machine setting is in Turkish! Getting to live in different places, not just visit for a few days, is a whole different level of life experience. Let alone raise your children or navigate new work environments in different continents. You learn so much about yourself. It’s exciting and educational, but also humbling and challenging. It has definitely made me more empathetic. And over the years, it has also made me appreciate where I come from, my Mediterranean roots.

A journalist, a Communications & Marketing Specialist at Michigan University, a writer. Where do all these different attributes meet? Is there a binding thread?

The need to establish some meaningful contact with an audience. Last year I gave a TED talk on the difference between communication and contact, where they meet, how they compliment or differ from each other, emphasizing the role of language in each one. I drew most of the examples from my professional life in media and communications, but also from my family life in a bilingual household, from the experience of being an immigrant. But they all meet at this one point: the deep, undeniable urge to build a bond with someone, either a specific person or a diverse audience, and the fulfillment you experience when this is done right.

As a journalist, you have been following the rise of far-right powers and ideas in society and politics both in Europe and the USA. How do you experience what your friend and colleague at the University of Michigan, Vassilis Lambropoulos, studies/analyses as “left-wing melancholia”?

The talks we had with Vasilis (and the brilliant Greek community in Ann Arbor) was the inspiration of the weekly column I ran on Vogue, The Gen X Mess. Very different content of course, but my idea had the same melancholic realization: that we saw all of our ideals crumble and disappear, we never had a chance to achieve the full potential of our promised future, we only got to glance at a dream world before it came crashing down. It spoke about the Athenians of my generation who danced on the streets during the summer of the Olympics and we thought, this is it, this is just perfect, and a few short years later we saw the mobs of the Golden Dawn members take over the same streets. It spoke about the women of my generation who demanded and achieved the educational and professional opportunities that our grandmothers could only dream of, only to find ourselves very shortly after watching debates on daytime TV about whether a murderer loved his victim too much and this is what drove him to femicide. There was this point when we felt we had left so many of the problems behind, we were so close to reaching a new, enlightened and fair level of quality of life and it just stopped abruptly, like a scene from a ‘90s movie when the record skips and makes a horrible screeching sound. There is this iconic picture of an older woman carrying a sign that says “I don’t believe I still have to protest this shit” and I think it sums up in the best way possible how we feel.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE