Hilda Papadimitriou studied Law and since 1994 has been professionally involved in literary translation (among others: John Barth, Percival Everett, Jonathan Coe, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Nick Hornby, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Ross McDonald, Joyce Carol Oates, Yoko Ogawa, etc.), as well as with the translation of essays concerning music and the fine arts (The Sound of the City, ed. Livani, Neoclassicism, ed. Kastaniotis), and the history of political movements (A generation in motion, ed. Koukida).

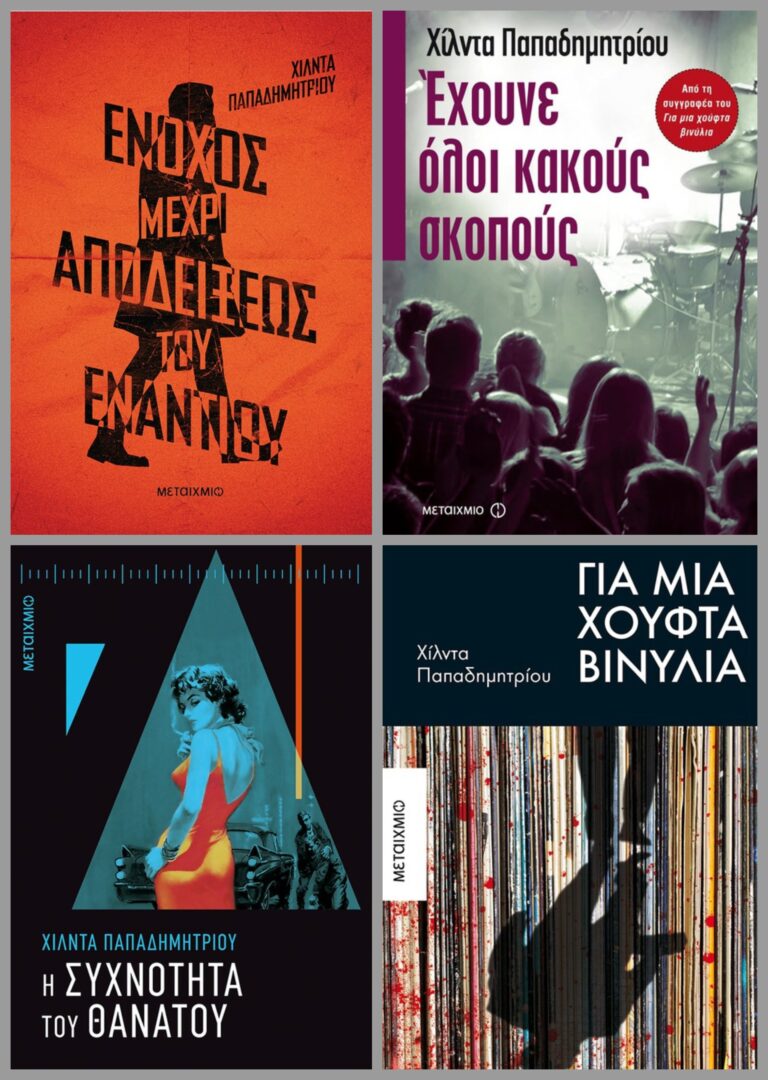

Since 2010, he has been writing crime fiction novels (For a Handful of Vinyl, Everyone Has Bad Intentions, The Frequency of Death, Guilty Until Proven Innocent, published by Metaixmio). She has taught crime fiction translation at the National Book Center of Greece (EKEBI), and is a regular contributor to the online book magazine www.bookpress.gr, the online music portal www.mic.gr and the Greek Rolling Stone.

How did your involvement with crime fiction begin? Would you say that there are recurrent points of reference in your books?

My mother was a crime fiction and film noir fan, so I became addicted too. I listened to the crime series with detective Bekas on the radio and I was excited by adventure books. I never stopped reading detective stories, and when I learned that Brecht, Borges, and Gramsci were fans of the genre, I gained the theoretical knowledge to support them internally—I mean, not feel guilty about not reading other, more “serious” books.

In my books, I return to my favorite crime fiction genres, hardboiled and noir, in the sense of morality that permeates the classic crime novel, the need for justice and forcatharsis. In addition, the first three were a musical trilogy about my own obsessions: record stores, young rock bands and independent music radio stations.

Tell us a few things about your protagonist, Haris Nikolopoulos? How has he evolved over the years? What is that makes him such an appealing literary character?

I had thought of Haris Nikolopoulos as a secondary hero in Για μια Χούφτα Βινύλια [For a Handful of Vinyl], but because he was an anti-hero since the beginning, he won the bet, the readers loved him as much as I did. Harry is not pretentious at all, he is not pretending to be the cruel and cynical detective; he is a righteous policeman who tries to do the right thing. Over time he becomes less lonely, learns to make friends but also to live alone, with his books and his dogs. In each book he takes a step: small or large, yet important for him. At the end of Vinyl he leaves alone for London, to visit the city of the Beatles and Agatha Christie.

At the beginning of Έχουν Όλοι Κακούς Σκοπούς [Everybody Has Bad Intentions], he has rented his own house and is living with a Dutch woman. In the third book of the series, Συχνότητα του Θανάτου [The Frequency of Death], he lives a passionate love story and, disappointed with himself and the police, resigns and settles in his hometown, Nafpaktos. Finally, in Ένοχος μέχρι Αποδείξεως του Εναντίου [Guilty Until Proven Innocent], he returns to Athens and goes underground, when he unwittingly becomes involved in a murder that he fears his former colleagues will not help him solve.

In short, Harry grows old, matures, gets hurt and learns to deal with pain; he experiences the tragedy that a serious illness and the loss of his parents represent for all of us. And perhaps all these psychological changes of his remind the readers of their own small and big tragedies, and that is why they have loved him so much.

Since the mid-1980 there has been a revival of crime and noir novels in Greece. How is this trend to be explained? Does crime fiction also constitute a way to talk about contemporary and social issues, such as racism, human trafficking, corruption etc?

For many years in Greece there was a disdain for crime fiction, as intellectuals considered it pulp fiction. In addition, the unfortunate rendering of the term crime fiction as detective fiction, was a red flag for those who did not have good relations with the Police Force due to political beliefs. This is how the patriarch of crime fiction in Greece, Yiannis Maris, was almost forgotten. Greek crime fiction restarted thanks to Petros Markaris, an intellectual who also appreciated good detective fiction books. I think that the example of Markaris, but also the emergence of other national schools of crime fiction, opened the way for many Greek writers who loved this genre. And of course, the huge success of scandi noir, crime series that are now streamed on all channels and platforms. The truth is that crime fiction is perhaps the only genre that does not hesitate to raise key social problems, such as racism, trafficking, the entanglement of the authorities with organized crime.

“As a translator, you study the structure of a novel. You learn how not to make the narrative sag, how the dialogue should flow so that narration comes natural”. Where does the translator meet the writer in your work?

Just as you said, a translator’s eye picks out the mistakes and longueurs of the plot and makes sure to correct them. Translation is a great school, when you love it and do it with passion. You learn to distinguish the style, adapt to it and find ways to render the dialogues in natural language. A good writer is a careful reader, and what reader is more careful than a translator?

You have translated major writers in Greek, such as Malcolm Bradbury, John Barth, Jonathan Coe, Percival Everett, Dave Eggers, Mary Gaitskill, Jane Smiley, David Malouf, Nick Hornby, Siri Hustvedt, Raymond Chandler, Agatha Christie. Which were the major translation challenges you have been faced with over the years?

The biggest challenge I have been faced with was the embedded novel within the book Erasure by Percival Everett, which was written in ebonics, the African-American dialect. From John Barth I learned how to translate postmodern writers, where every word has its place and its weight. The challenge to Raymond Chandler was to convey his old-fashioned slang and venomous humor. Every book is a challenge, or so the serious translator should treat it.

In an interview to Reading Greece, Elena Pallantza emphasized on the “artistic dimension of a translator’s work”, who “seeks to literarily address the problem of silence of a text in a foreign language”. Would you agree that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value?

Absolutely. Translation means entering another person’s universe, finding the style and atmosphere of the book, the time and place where its plot unfolds. It is a pity that in our country there is so much indifference to the work of the translator – and the editor, I might add.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

A translator’s job is to render the peculiarities of each language into his/her own. But at the same time the literary style of the author, the atmosphere of the era, the vibe of the country. And it is the responsibility of the translator not to be tempted to “correct” the author or to resort to the easiest solutions. A good translator is, among others, an avid reader who understands the seriousness of the translation venture and strives over the text, with respect for the author as his/her main concern.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE