Iana Boukova is a Bulgarian poet and writer. Born in Sofia in 1968, she has a degree in Classics from Sofia University. She is the author of three poetry books, two short story collections, and a novel. Her poetry and prose have been translated into numerous languages, including Spanish, French, German, and Arabic. English translations of her work have appeared in Best European Fiction 2017, Words Without Borders, Two Lines, Drunken Boat, and Absinthe, among others. Boukova is also the translator into Bulgarian of more than ten collections and anthologies of modern and ancient Greek poetry, including Sappho’s Fragments, the collected poetry of Catullus, and the Pythian Odes by Pindar.

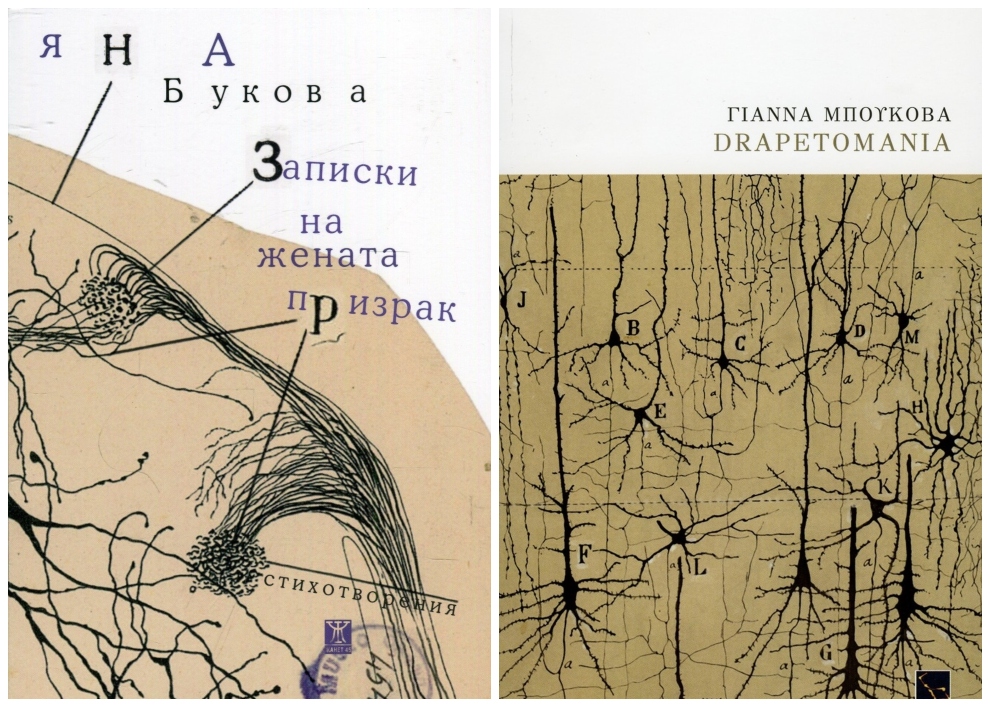

She has lived in Greece since 1994 where she has collaborated with a number of literary and cultural magazines. As a member of the platform Greek Poetry Now she takes part in various poetical actions, performances and public readings. She is one of the members of the editors board of FRMK, a biannual journal on poetry, poetics and visual arts. Poems by Iana Boukova written in Greek have been included in Austerity Measures: The New Greek Poetry, Penguin 2016 and Kleine Tiere zum Schlachten. Neue Gedichte aus Griechenland, parasitenpresse, Köln 2017. Books in Greek: The minimal garden, Ikaros 2006, Drapetomania, Mikri Arktos 2018.

Your last poetry collection Notes of the Phantom Woman received the Ivan Nikolov National Award for the most outstanding book of Bulgarian poetry in 2019, while a Greek-language version of it was also published in 2018 in Athens under the title Drapetomania (Mikri Arktos). Tell us a few things about this writing venture of yours.

It was an unprecedented experience for me. I had written in Greek in the past – essays, reviews, some scattered poems. I had also started an entire poetic project based exclusively on the use of the Greek language and the ‘twisted’, free in associations, foreign look on it. It is the ‘S’, which is to be published later this year, an effort-wager to define in a metaphorical and inventive way all the Greek nouns that start with this letter.

Yet, what happened with the texts of Drapetomania is that they were written simultaneously in two languages, Greek and Bulgarian. That is, there are two original texts and both books were published in the same year, 2018, both in Greece and in Bulgaria. It was a strange moment of balance, where the stimuli were reaching me through two languages and there was a strong desire on my part to address at the same time two –consolidated and precious to me – audiences in both countries. I am not sure if a similar balance will ever be achieved again in the future, that is, if what happened is a new beginning or an exception. In any case, it was a very liberating way of working. It was as if the two languages cooperated, complementing each other. At some points, where I had difficulty, the solution often came according to the potential of one language and the other followed. As if each language broadened the horizon of the other.

To use Adrianne Kalfopoulou’s words, “the poetry of Iana Boukova explores a personal mythology in non-sequencial and asymmetrical narratives, juxtapositions of image and histories that are also mythological (Balkan and Greek) which scramble time and place where dreamscapes enter into her speakers’ waking moments“. Which are your main themes your poetry touches upon?

I find it difficult to talk about themes in my poetry; I’d rather talk about ways and strategies. My intention is for my books to be quite different from each other. Adrianne’s apt words refer more to my previous book of poetry, Minimal Garden. In Drapetomania, I wanted to change the ingredients of my writing, to use less elaborate, less ‘poetic’ materials. I was attracted to the use of encyclopedic information, a plain reporting of historical events or scientific findings. I was interested in whether the use of such material could prove functional in a poetic composition.

I belive that the inner rhythm of my thought has not changed in relation to my previous work. Simply as a structural unit in place of the image or the elaborated poetic phrase I use facts, pieces of scientific discourse, ‘stray’ verses, sayings, pseydo-sayings. Especially the latter was for me a very functional means to talk about issues that I find difficult and important. Self-undermining and self-irony of a truth paradoxically (or not) make it moretruthful.

“Poetry explores the real world around us and within us in a crude and unconditional way“. Ηοw does literature relate to the world it inhabits?

I reckon that nowadays we have no choice but to learn to use the way of poetry to walk in the world. Given that everything is fluid and that there are no indisputable philosophical systems, nobody can endow you with a worldview. You have to build your own. Poetry offers you the tools to do so. It educates you to detect connections between the pieces, to articulate phrases amid the general noise. In other worlds, it trains you to keep balance on a ground that is far from solid.

Being the editor and award-winning translator into Bulgarian of more than ten collections and anthologies of modern and ancient Greek poetry, how pivotal is the role of translators in acquainting foreign readers with a country’s literary and cultural heritage? In this respect, how important is for a country to avail of a translations funding program?

I find it sad and heartbreaking that we are even discussing this issue, which is so clear and self evident. Indeed the role of a translator is undoubtedly important, indeed his/her job should be financially supported. Yet, most translators work with no support whatsoever, underpayed or unpaid, driven only by their love for literature and their responsibilitytowards language.

“To translate from minor to major languages is an act carried out against the law of gravity. That is as if you were pushing water upslope. Not undoable, but, to do it, you need an entire mechanism, energy consumption, and a collective endeavour“. Could you elaborate on this argument?

As much as we may not like such labels, the existence of ‘minor’ and ‘major’ literatures is a reality in terms both of their recognizability, and the weight of the renowned names, as well as in terms of the size of their markets. The laws of this reality are as irrevocable as the laws of physics. I insist that numerous and coordinated efforts are required: funding of translations and publications, promotion of translated books abroad, grants that support translation projects, scholarships for foreign students and incentives to engage in literary translation, support of university chairs of language abroad…

The paradox is that the book as a product is quite cheap, it requires a relatively low cost. Dozens of books would be translated and published at the cost of a symphony orcherstra travelling abroad, or with a budget of short movie. Yet, no one seems willing to bear this cost. Investing in books is long-term, it doesn’t bear fruit immediately. One cannot take beautiful photos, nor make impressive openings. There is no political profit to be gained given that it moves beyond the limits of one governmental term in office, requiring both continuity and consistency. This is probably the reason why there is no political will to support the book.

Which would you say is the impact of the current health crisis on literary, and more generally, artistic production?

I won’t talk about the practical issues and difficulties: much has already been said in this respect. There is something deeper. What happened with the pandemic – which I hope is gradually receding – is a disturbance in the very sense of reality. A sudden shortage of reality. All those crutches of everyday life that supported a certain image of a self disappered from one moment to the next. We found ourselves in limbo – for better or for worse.

Art proved quite unarmed in this situation. Themes and practices that until recently seemed clever and fun suddenly turned out be be superficial and pointless. As if a demand for a change in art, the need for more existential depth, for more seriousness, was imposed – in the hardest and strictest way. Will this shift of perspective prove persistent when we return to the so-called normality? Most likely not. But just realizing how fragile the image of the world is and how vulnerable our own limits are is a great lesson for an artist.

A poet, novelist, essayist. Where do all these attributes meet? Could language, in its various forms, hold the binding thread?

I consider that the general approach to writing, that is the philosophy of a writer’s text doesn’t change from one genre to the other. For me, as I always say, the elliptical character of speech, the mental game with fragmentation, the balance between what is said and what remains unsaid in the sturcture of the text is what is important. What I do with the phrases and verses in my poetry is almost identical to what I do with my stories and narrative pieces in my prose.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*PHOTO IMAGE: Giannis Isidorou [At the stand of FRMK magazine, Thessaloniki International Book Fair (2016)]

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE