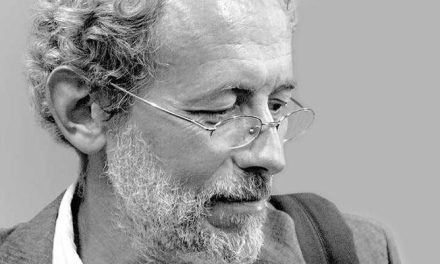

Iannis Kalifatidis is a distinguished translator whose translations of major German-speaking writers have won him several awards. After his High School degree at the German School of Athens in 1982, he studied Mineralogy at the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany and attended seminars in Modern Arts, organized by the University of Tübingen. He worked as a Scientific Associate at the Hessisches Landesmuseum of Darmstadt, in particular at the Joseph-Beuys-Block and at the Department for Palaeontology. He has a long career and rich discography in the alternative music scene as a songwriter and guitarist. After settling back in Athens in 1999, he studied at the European Translation Centre for Literature & Human Science (EKEMEL) and acquired his diploma in German-to-Greek Literary Translation. Since then he has been working as a translator and editor for various publishing houses.

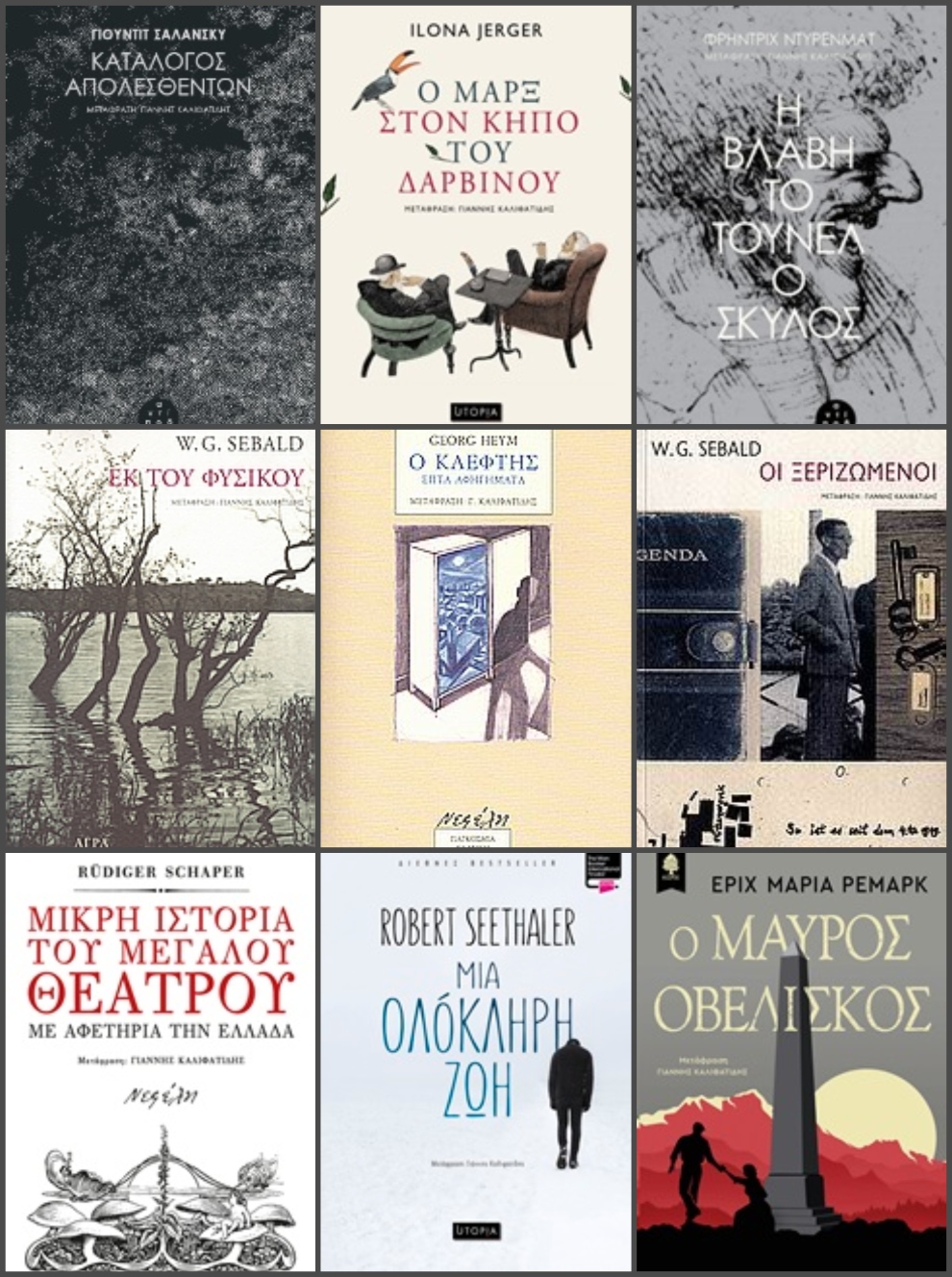

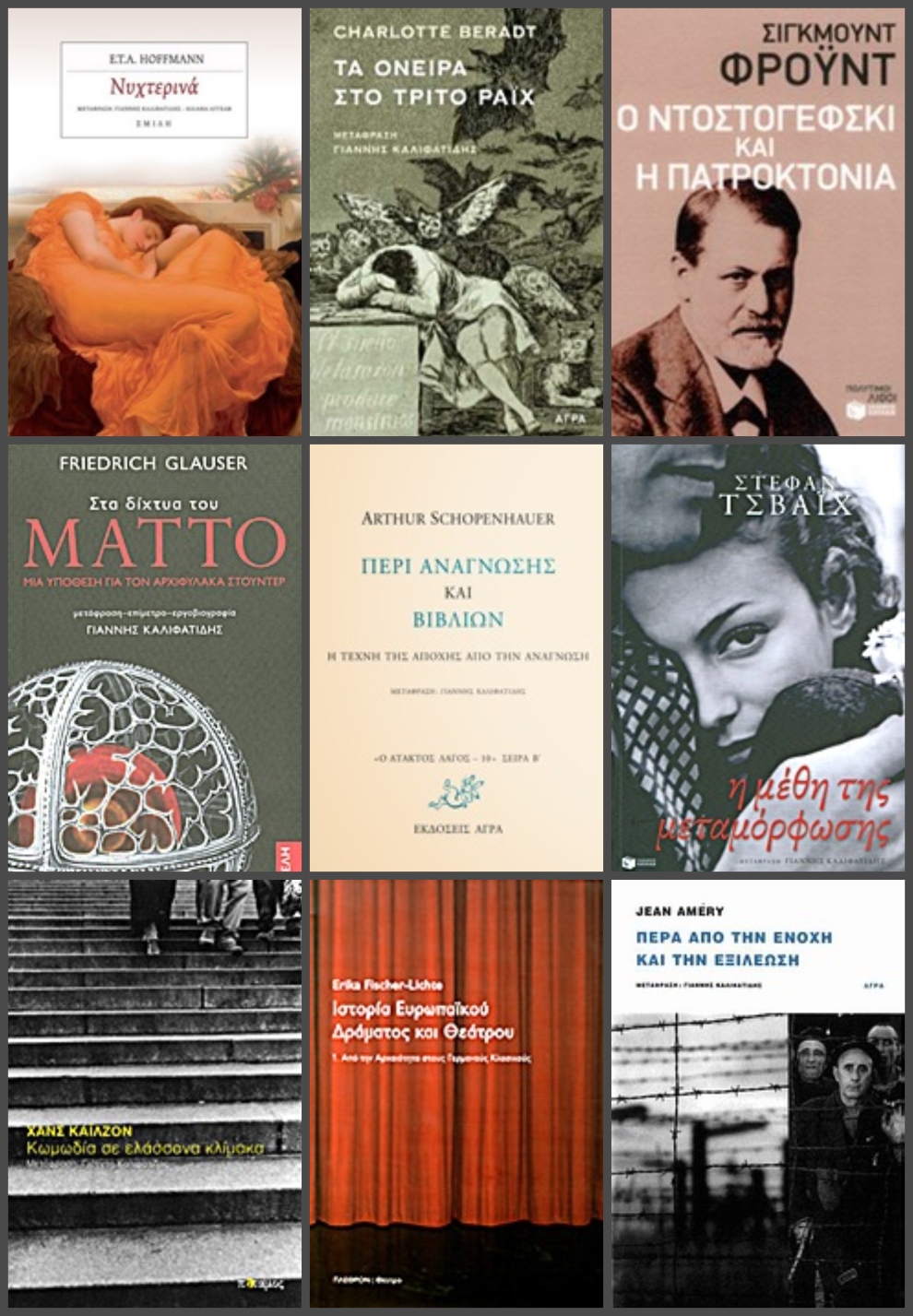

For his translation of Die Ausgewanderten by W.G. Sebald he was awarded the National Prize for Literary Translation 2007, granted by the Greek Ministry of Culture; for his translation of Georg Heym’s Der Dieb. Ein Novellenbuch he was awarded the Prize for German-to-Greek Literary Translation 2010, granted by the Goethe Institute of Athens in collaboration with EKEMEL. He has taught Greek-to-German Literary Translation both at EKEMEL and at the Goethe Institute of Athens as well as at KOLLEG. He was granted various scholarships and residencies by state and cultural institutions in Germany, Switzerland and Austria.

You have translated major German-speaking writers in Greek. What made you turn to literary translation? What continues to be your driving force?

I have been translating German literature since my late youth, as a part of a wider process of discovering and developing my own voice, since I was also writing and still write song lyrics in English and poems in Greek. Everything started in the early eighties, when, as a university student in Germany, I had the chance to discover a vast variety of fiction books, some of which were not published in Greek back then. I recall that I had finished translating Gerhart Hauptmann’s novel Bahnwärter Thiel and that I wanted to get in touch with a Greek publishing house to offer them the translation, only to discover that in the meantime the book was published in Greek, which was probably a turn of good fortune, since my translation was still rather amateurish, I guess, meaning that I hadn’t still captured the voice of the author. When I returned to Athens, after seventeen years in Germany, I studied for two years at the European Centre for Literary Translation (EKEMEL), which helped me a lot to understand how things work with translation. I think that the driving force has always been my love for literature. This is my way of contributing to a cultural dialogue, or to serve as a bridge across the linguistic Babel.

Which were the main challenges you were faced with while translating major writers such as W. G. Sebald, Georg Heym, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Judith Schalansky, and so on?

Well, I’m quite happy you mention four writers so different one from another. It is rather challenging to become, so to speak, the author and rewrite his/her books in your own language. That is like becoming an actor who actually plays all the roles in a play, which demands faith and respect towards the work of literature. The only way I know how to do it properly is to live it out. Translating an author is like living with him/her for quite some time. And every time you need to invent a new language, in order to translate a piece of literature. And of course you need to dive deep into the author’s world, in order to become his/her voice in your own language.

“Translating for me is like writing music, both governed by a mathematic logic, a bit like an algorithm.” Tell us more.

To me, words and phrases work like musical notes, perhaps because of my music background. So they don’t form literature or music themselves. They are only the means to composition. You need to hear out the rhythm, the melody and the magic, to understand them as a formal medium of expressing pictures, sceneries and feelings. Thus, imagination and logic are the main tools for a translator, regarding time and space. The algorithmic approach is like finding a way to invent a formula which helps you to translate a piece of literary work. You have to create a new concept of tonality, like in the mirroring compositions of Arnold Schönberg, which means that you need to restructure and reshape the original text, so that it’s going to work in the target language. At the end of the day, you want to have a text which works perfectly in Greek, as if it were written in Greek, yet still maintaining its foreign characteristics.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

When you translate a foreign book you need to do it vis-à-vis the original cultural context. It is vital to bear in mind that the story takes place in a completely different universe, where not only the landscapes and the structure of the cities, but even the gestures and the whole language of the body are different, e.g. in German and in English it is common to say “he lifted his chin”, while in Greek you’d rather say “he lifted his head”. Of course the translation is Greek, but the scenery is not. I guess that an unethical translation is the one that does not pay attention to the author’s stylistic elements, to his/her background, place and role within a particular literary era. One of the main challenges in translation is how to deal with the realia of everyday life, history, culture, politics, etc. of a certain people, country or place.

In an interview to Reading Greece, Elena Pallantza emphasized on the “artistic dimension of a translator’s work”, who “seeks to literarily address the problem of silence of a text in a foreign language”. Would you agree that translation is an autonomous act with its own artistic and aesthetic value?

Yes, I would rather agree with Ms Pallantza, and I find her thesis quite fitting to describe the process and the value of translation. It is a creative attempt which seeks to overcome silence and break the linguistic barriers. Of course it is not autonomous, in the sense that you work on a given piece of literature, yet still you use all the tools I mentioned above to keep the translation as close to the original, but without betraying the artistic and aesthetic dimensions of the narrative in the target language. After all, translation is also interpretation.

Yet, could translators also act as cultural ambassadors fostering understanding between different countries and cultures?

Well, that is what translators are indeed: cultural ambassadors. They actually act as bridge-builders between countries and cultures.

GreekLit, a new translation funding program has recently been launched by the Ministry of Culture. How important are such initiatives for the dissemination of Greek Letters internationally?

Culture is one of the main export goods Greece has to offer. Especially since the economic crisis, but even before, young people have been trying to find ways to express and engage themselves in various fields of art – literature, music, fine and performing arts, dance troupes or theatre groups. So, yes, I believe that programs such as GreekLit are truly essential for the international acclaim of Greek Letters, and I would very much welcome similar initiatives for the support of other artistic and cultural activities, too.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: © Γιάννης Αντύπας/ FOSPHOTOS

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE