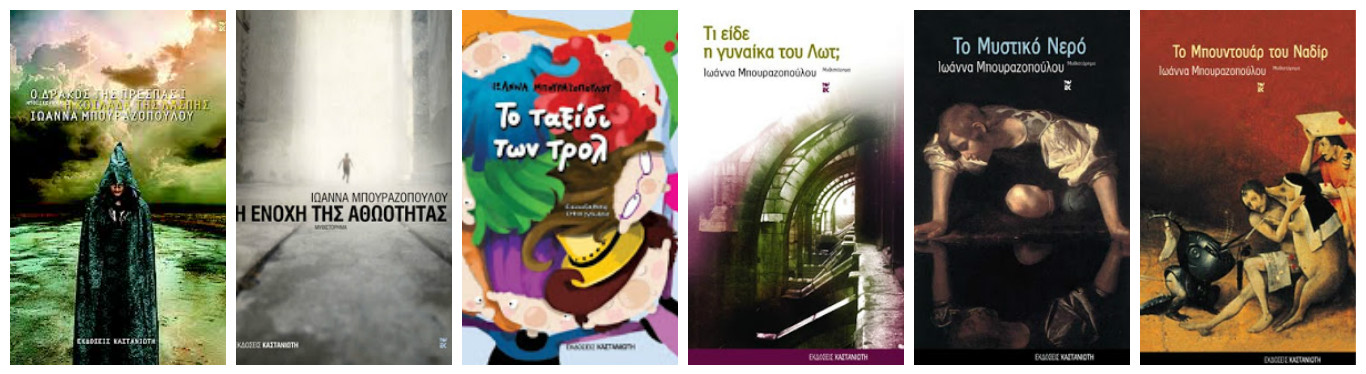

Ioanna Bourazopoulou is a Greek playwright turned novelist. She has written five novels: The Boudoir of Nadir (2003), The Secret Water (2005), What Lot’s Wife Saw (2007), The Guilt of Innocence (2011) and The Valley of Mud (2014), the first part of the Trilogy The Dragon of Prespa. What Lot’s Wife Saw, awarded with the prestigious 2008 Athens Prize for Literature, was among the Best Science Fiction Books of 2013 according to The Guardian and was translated into English and French. The Valley of Mud received the Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation literary award in 2015. Ioanna Bourazopoulou was among the Greek writers who represented the country in the 29th Moscow International Book Fair, where Greece was the Guest of Honor.

Ioanna Bourazopoulou spoke to Reading Greece*about her latest book The Valley of Mud, commenting on how her books combine fantasy and symbolism with political allegory. She characterizes words as the “tools of her art”, noting that during the current crisis “words have been manipulated to support conflicting arguments and to make up for the lack of reasoning”. Arguing that novels constitute byproducts of the crisis, she concludes that what literature needs today is a new language, which may in turn lead to a new life approach.

The Valley of Mud – the first part of the trilogy The Dragon of Prespa – received the Kostas and Eleni Ourani Foundation literary award in 2015, a daring choice for an established foundation. What is the theme of the book? Why did you choose the area of Prespes as the setting of your trilogy? What about the next two parts?

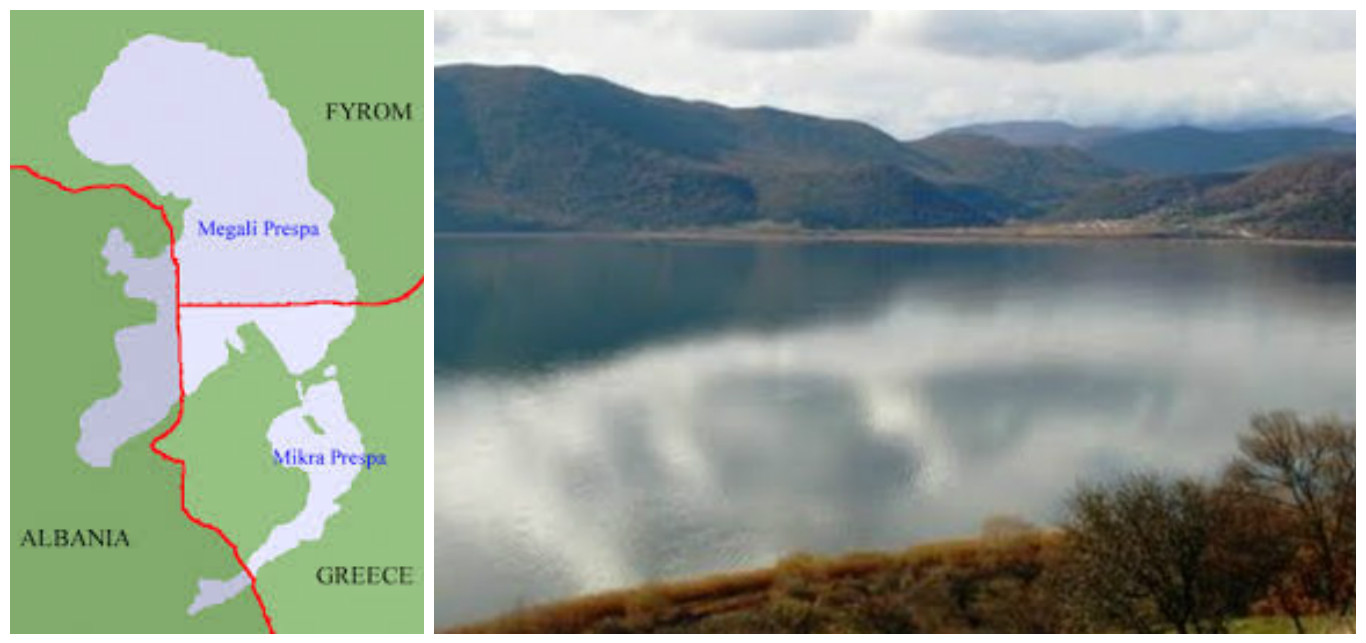

Great Prespa is a lake shared by three small Balkan countries – Greece, Albania and FYROM. The lake, which constitutes their natural border, both unites and separates the three countries. It constitutes a long-suffering crossroads whose populations have been plagued by world wars, ethnic divisions and international power games, while they have been confronted with prejudice, migration and the ferocity of national fanaticism.

It is in those water borders, according to the book, that a mythical monster, a dragon, appears; nobody has seen it in person but everybody feels the destructive consequences of its presence. Fortunately (or not), the dragon attracts the interest of global capital, which hurries to invest in the region. Hope is rekindled in the three small countries, which start to compete in order to ensure the exclusive rights to the disastrous monster.

The first part, namely The Valley of Mud, describes what goes on in the southern bank of Prespa, the Greek side of the border. The next two parts depict the events that take place on the lake banks in the other two countries. Each part offers its own answers to the mystery of the dragon according to the viewpoints of the citizens of each country. Yet, when reading the trilogy in its entirety, it becomes obvious that events are interrelated and that reality is much more complicated.

“Perhaps reality is but a mass delusion,” muses detective Phileas Book, in the opening sentence of What Lot’s Wife Saw. How are fantasy and symbolism combined with political allegory in your books?

Hopefully in tandem, as each enriches or restrains the other so that narration is at the same time realistic and magical. Fiction allows me to lay out fascinating worlds without being patronized by the preoccupations of current affairs or the banalities of reality; on its part, political allegory helps keep my inspiration within the framework of realism so that the reader doesn’t feel intellectually offended, while symbolism ingeniously unites dreams with experiences. It’s a mixture that as a writer I find liberating and at the same time self-restricting; it works for me and I hope that my readers enjoy it the same way I do.

“Words are my whole existence. I think, feel and breathe through them, although they still deceive and terrify me […] And when the words you know are not enough, invent the words you need, give them the strength that you miss”. What drove you to writing? Is it necessary to come to a standstill in order to invent or express something new? Do your “new words” require a new approach to life as well?

Words are the tools of my art; without them I have no voice let alone any thought. As long as words are filled with meaning, what I create is full of liveliness, when words are repeatedly abused or distorted notions seem weak and annoying.

The current economic crisis has led to a social crisis, a crisis of values, which has in turn influenced public discourse, news reporting and everyday communication. Political notions have lost their meaning the same way that bank notes have, given that words have been manipulated to support conflicting arguments and to make up for the lack of reasoning. Now that the economy is in search of new rules and society is in pursuit of new political ideas, what literature needs is a new language. I agree that a new language presupposes a new life approach, but at the same time I believe that it can provoke a new life approach itself.

“We are a country of dead heroes and kings, drawing its self-esteem from a glorious past. Preoccupied with proving what we once were, we are unable to see what we have become: a boat full of weary companions heading towards an even more distant Ithaca”. Tell us more.

I wish we would love our country and ourselves for what we are now, not for what we once were, because this is the only way to learn from our mistakes and soberly deal with the challenges that lie ahead. We honour our past but we are not oppressed by it, nor are we deluded by big words and shortsighted pursuits. The ever-changing global social and political environment asks for intellectual flexibility, presence of mind and maturity, traits that can in no way flourish when pursuing nationalistic fantasies.

You have said that your work as a public servant and writing are ‘communicating vessels’. Is writing a way to balance your everyday reality? Would you ever consider writing a realistic novel?

Writing science fiction helps me keep alive my faith in people, in dreams and miracles, every time reality puts me down, confines or disappoints me. On the other hand, I would never look for a way out in literature were it not for the stimuli of reality. When I was younger, I was convinced that the two sides of my life – the professional and the artistic – were in constant conflict and that they would eventually tear me apart, but as I grow older I have come to realize that they are complementary, safeguarding my internal balance. This is actually the reason why I have never been tempted to write a realistic novel.

Is it true that Greek noir has become increasingly popular in the last few years? Is this growing appetite for a dystopian, rather dark landscape in Greek fiction associated with the broader socio-economic environment?

The crisis has undeniably pervaded our works, whether we like it or not. In the last decade I have never come across a novel written by a Greek writer – at least the ones I have read – that is not imbued with the grey shades of our national adventure, irrespective of the topic at hand. Our novels constitute byproducts of the crisis and they definitely resonate through the crisis, even if they are not solely focused on it.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE

![Literary Magazine of the Month: [FRMK] and its Ten-Year Anniversary Issue ‘Tenderness-Care-Solidarity’](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/04/frmkINTRO2-1-440x264.jpg)