Ioannis Balampanidis was born at Thessaloniki in 1980. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science and History from Panteion University of Athens. He is the author of Eurocommunism: From Communist to Radical Left in Europe (Polis, Athens 2015, and Routledge, New York and London 2018) and also member of the editorial board of the review Synchrona Themata. The short stories collection Largo is his first attempt in literature.

Ioannis Balampanidis spoke to Reading Greece* about his first literary venture Largo, which comprises “heterogeneous stories” dealing with “solitude, love, work, identity”, in which “the notion of time constitutes their binding thread”. He commented that the book “attempts to record the psyche of the generation” he himself belongs to, to “reflect part of the aesthetic taste of our generation – and simultaneously of our fragmented (individualised) world”, and concluded that the pivotal question in literature is “if and how we can live poetically in the world”.

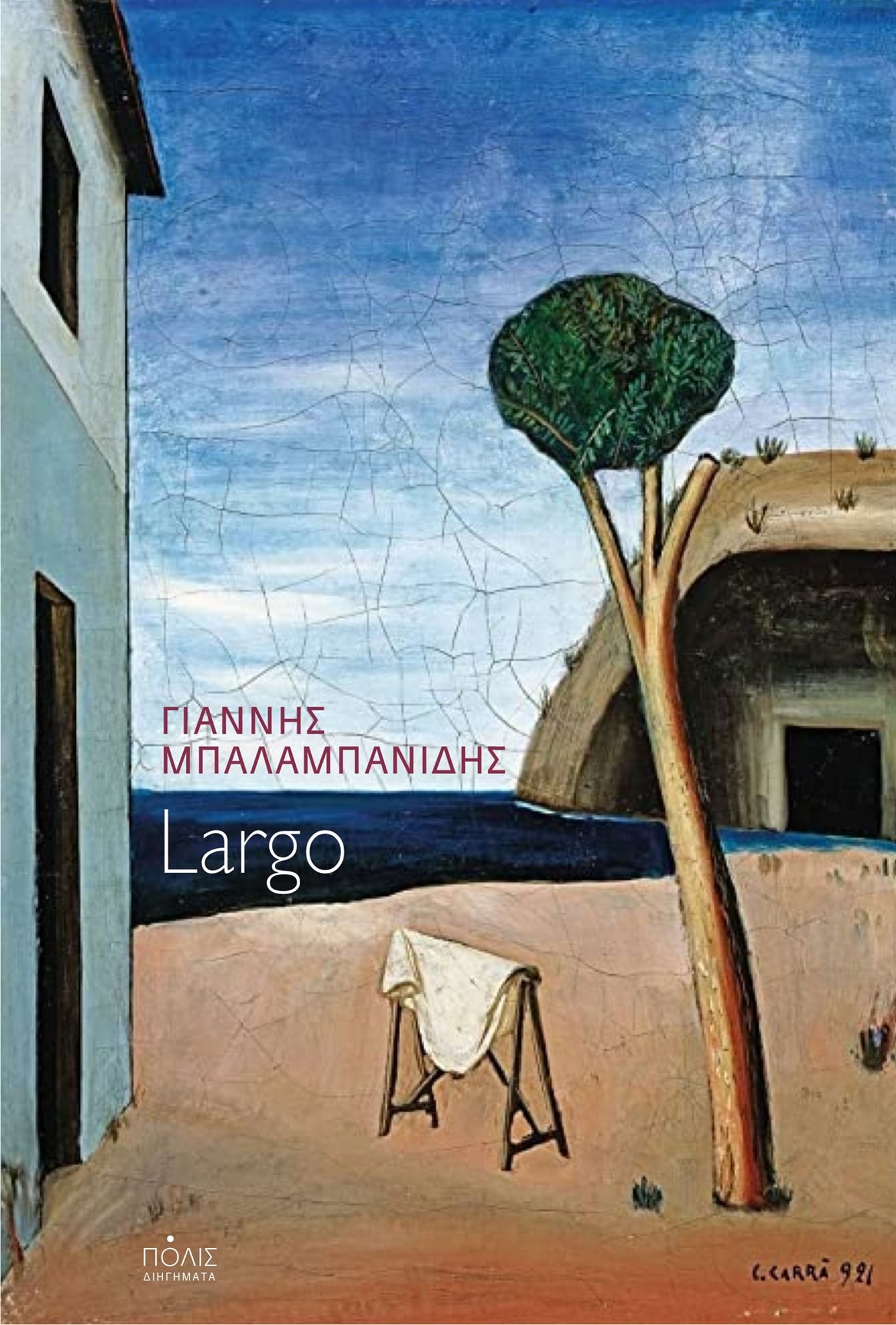

Your first literary venture, the short stories collection Largo (Polis, 2020) received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

Largo constitutes a debut book and it should be read as such. As a series of attempts, in which the writer as an amateur is experimenting (a more proper word would be ‘playing’) with various different expressive forms, literary genres and languages, in the narcissistic conviction that he has something very important to say. Undoubtedly an illusion, which however may at times create a real community of accomplices.

Although the stories included in the book are written in a distinct style, the unsolved question of time seems to be a binding thread. How is the notion of time dealt with in Largo? What role does language play in this respect?

The book comprises heterogeneous stories in search of a “unity within difference”. They deal with solitude, love, work, identity, but indeed the notion of time constitutes their binding thread – a time which is omnipresent, in a two-fold sense. On the one hand, as the great oppressor of our life and times; that’s the reason behind the book’s title Largo (a very slow musical rhythm), as a gesture of resistance, undeniably futile, against the frantic pace of our world. On the other hand, time here operates the same way as tempo in music: it condenses or spreads out, it pauses or pounders; the same melodic pattern played at a different pace can end up completely different. If we put words in the place of notes, we would say it is an étude οn language (to use once again a musical term).

“Largo constitutes a disguised ‘sociological’ look into the psyche of a generation that dizzyingly swirls towards the future, while at the same time remaining stuck in a nostalgia for something indefinable”. Tell us more.

Although not explicitly articulated, Largo attempts to record the psyche of the generation I myself belong to. A borderline generation; all those youngsters around 30 years old when the major, ongoing crisis of our era broke out. A highly educated and cosmopolitan generation, bearing high expectations of continuous improvement, and at the same time unsuspecting of the major frustrations it would be faced with. The eclectic materials these short stories are made of (paradox and realism, noir and science fiction, philosophy and comics, sublime and pop) reflect some part of the aesthetic taste of our generation – and simultaneously of our fragmented (individualised) world, which through its own defeat, is now in search of an underlying bond that holds together something like a collective experience.

Where does the political scientist meet the writer in your work? Would you say that political thinking and literature constitute communicating vessels?

I reckon that a scientific study is considered successful when it can be read as good literature. The same goes for the reverse: good literature doesn’t have much to envy of a good sociological research. This in no way means that there are no boundaries between the two. Social science and literature each have their own discipline, their distinct tools and methods. Yet, even through diverse paths, both allow us to approach our surrounding “reality”, to give shape and meaning to this chaotic world around us.

How does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to describe what could potentially be radically different realities?

Let me use the eloquent title of a recently published poetic anthology, borrowed by a famous verse of Hölderlin: the question is if and how we can “live poetically in the world” [Frédéric Brun (ed.), Anthologie manifeste. Habiter poétiquement le monde, Poesis, 2015]. As far as I am concerned, this is the pivotal question in literature. In other words, if one can move beyond simple representation and crude realism, to take a distance from reality, and to search for its multiple, contradictory, magical and paradoxical dimensions – in essence, to revisit it reflectively.

How do Greek writers relate to world literature nowadays? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

In many respects, Greek writers of around my age are absolutely cosmopolitan. They have lived or still live abroad; they read in many languages and are fully aware of international literary trends (and much more than that). Surprisingly, some often return to an “ethnographic” school, which is deeply rooted in modern Greek literature, searching for a kind of “authentic” language, occasionally away from urban life. This may constitute a way to interweave the local with the global. However, I consider this to be a bit artificial. Let’s admit that the chaos of the metropolis (Athens is certainly a case in point) is more than enough for us to immerse ourselves in and discover all the “crooked timber of humanity” we need.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE