John Taylor (b. 1952) is an American writer, critic, and translator who lives in France. After growing up in Des Moines, he studied mathematics at the University of Idaho, then literature and philosophy at the University of Hamburg (Germany). He also spent a year on the island of Samos, Greece, before settling in France in 1977. He is the author of thirteen collections of stories, short prose, and poetry. Many of his books have been translated into French, five into Italian, and one into Serbian, another one into Greek, while selected poems, stories, and essays have appeared in a dozen other European languages. He is one of the main bridges between contemporary European literature and English-speaking countries. His essays on European poets have been collected in his books Into the Heart of European Poetry (2008) and A Little Tour through European Poetry (2015). He has translated many French, Italian, and Modern Greek poets.

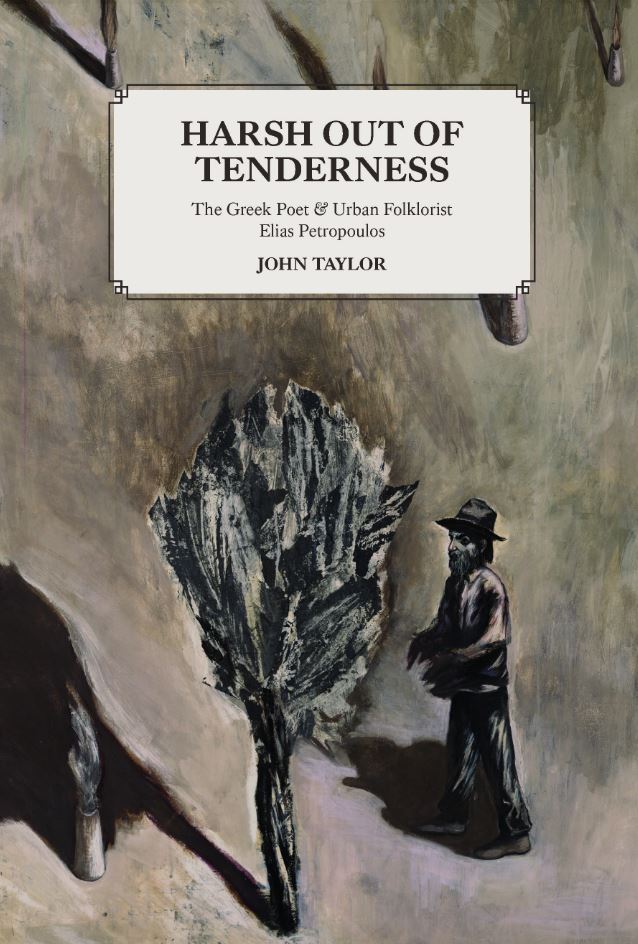

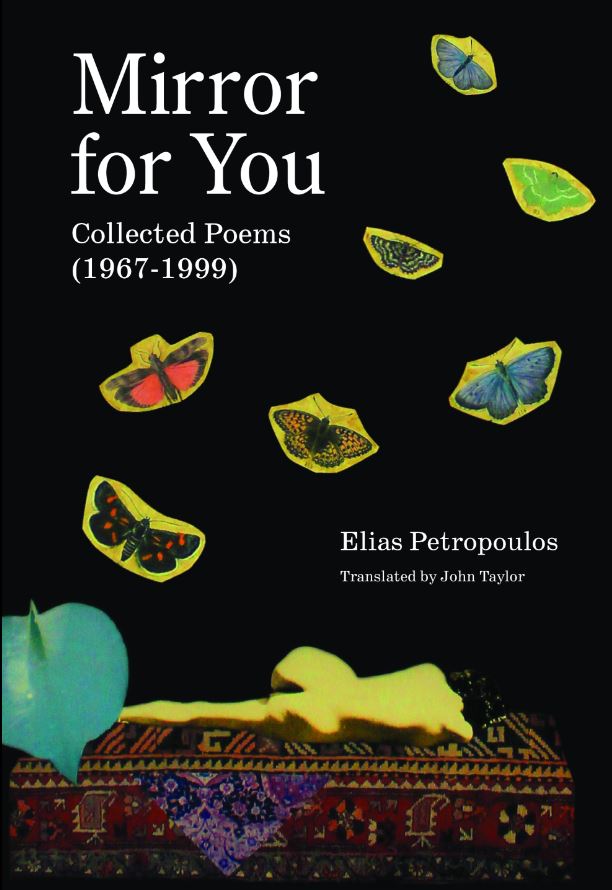

You have translated poems by urban folklorist Elias Petropoulos (Mirror for You, Cycladic Press, 2023) while in 2020, Cycladic Press published your memoir Harsh out of Tenderness, which details your experiences of working with Elias Petropoulos. Tell us a few things about both books.

Mirror for You: Collected Poems (1967-1999) gathers nearly all the poetry that Elias Petropoulos published. While putting together this comprehensive collection, I translated the Greek volumes published by Nefeli Editions, which include long-poems and long sequences of poems (and sometimes poetic prose), several of which were originally issued as bilingual bibliophilic editions illustrated by his artist-friends (such as Alekos Fassianos, Costas Tsoclis, and Michael Bastow) and also sometimes translated by me. I also added the ten poems written for the younger artist Dimitris Souliotis, whose paintings Petropoulos much admired (and whose compelling evocation of Petropoulos graces the cover of Harsh out of Tenderness). I therefore began this project in the early 1980s, after I had met Petropoulos in 1979. This gathering, which includes revised versions of my early translations and all the previously untranslated poems, represents the first time that his poetry has become widely available in English.

The second book, Harsh out of Tenderness, narrates my memories of working closely with him, in Paris, especially during the period 1979-1987, when I was also living in the French capital and, in fact, could reach his apartment by walking only ten minutes down the avenue des Gobelins and then up the rue Mouffetard. In order to write this book of memories about an out-of-the-ordinary personality whom I knew well and who was often, and sometimes notoriously, in the public eye, I created a guideline for myself: I would stick to events that I had eye-witnessed. This rule implied that nearly all the scenes evoked or described in the book took place during Petropoulos’s Paris years, which began in 1975. I also decided to avoid psychological analyses about what the poet and folklorist “was like,” even if my title, Harsh out of Tenderness (which quotes a line from one of his poems), already indicates that my anecdotes reveal hidden aspects of the man behind the sulfurous reputation.

In all cases, I eschewed hearsay, which is particularly widespread and tenacious in his regard. In fact, I first wrote down many of these memories strictly for myself, beginning only a few days after his death on September 3, 2003. And the form that I spontaneously gave to them recalled stylistic and narrative aspects of Petropoulos’s own writing. Later, as the manuscript was growing almost in spite of myself, I used a collage-like approach to arrange my recollections amid more objective critical passages about his books. I wanted this simultaneous memoir, tribute, anthology, and introduction to resemble his own writings. My Australian publisher, Michael Alexandratos, at his Cycladic Press, then created a section comprising numerous photos of Petropoulos and documents related to my text. I can now announce with enormous pleasure that Harsh out of Tenderness, in Yiorgos Allamanis’s Greek translation, will be published in late August by Dichty Editions (Εκδόσεις Δίχτυ) and will be in Greek bookshops for the twentieth anniversary of Petropoulos’s death.

How did your involvement with the life and work of Elias Petropoulos begin?

I met Petropoulos by chance. I arrived in Paris in 1977 from the island of Samos, where I had spent the previous year. One day, two years later, I tacked up a want ad in the Greek bookshop that was then located on the rue des Patriarches, near where he and Mary Koukoules lived, because I was seeking a Greek partner for a poetry translation project. Petropoulos, of whom I had never heard, answered the want ad, stipulating that the two Greek poets—Kostas Karyotakis and Yannis Ritsos—whom I had mentioned on my card should be disqualified because “one was dead and the other an idiot,” and declaring that he was seeking a translator for a book called The Good Thief’s Manual. We eventually got together at his apartment. During the eight years that followed, I saw Petropoulos at least once weekly (and more often, two or three or four times a week), for an hour or two or three each time.

I became his translator, a sort of English-language secretary for him, as well as the foreign critic who was writing the most extensively about his books. In addition, with respect to my own desire to be a writer, I had the inestimable fortune of being his “apprentice”—an odd term in our age of academic creative-writing programs and workshops, but no other word is appropriate. He never read my poems or short stories in manuscript before they were published, but as I was working with him he inevitably turned into my redoubtable mentor. As a mentor, he was exacting, but also patient and generous. Because he was a man of extreme passions and enthusiasms, this equation should be understood as extremely exacting, extremely patient, extremely generous. Our last long telephone conversation took place in September 2002. He related, all the while dismissing, the problems that he was having with his prostate cancer. I then visited him in the Clinique Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, where he was dying, and I was present at his final controversial act: in accordance with a poem-testament published in his collection Never and Nothing, the original Greek edition of which I had prefaced and which is comprised in Mirror for You, his ashes were dispersed in a Paris sewer.

What is that makes the work of this enfant terrible of Modern Greek Letters so notable and groundbreaking?

In Harsh out of Tenderness, I highlight Petropoulos’s countless contributions to all sorts of marginal topics, ranging from prison life, rebetika music, homosexual slang, traditional food, “popular” architecture and public hygiene to the sociology of brothels, newspaper stands, moustaches, canes and gravestones. In his day, such subject matter was ignored or scorned by nearly all academics, and when a researcher did show some interest in risqué or overlooked topics, the results tended to be more theoretical or politically biased than rigorously and extensively factual. Petropoulos was fascinated by details and he insisted on the necessity of first collecting all the facts and images—his particular way of using photography to document ordinary reality was also pioneering—before constructing the slightest sociological, ethnographical or folkloristic theory.

His findings induced him to reject, for instance, through extensive documentary proof, the “Greek” origins of some “typically Greek” objects and folkways. Fundamentally, he was skeptical of abstractions, ready-made definitions, quick conclusions, not to mention nationalistic biases in academic research. For readers who accept the sometimes abrasive, sarcastically funny tone of his folkloristic writings, which are otherwise full of details, expressions, photos, postcards, engravings, and other rare archival material, his calling into question of preconceived notions and theoretical elaborations can be salutary. He makes a well-founded appeal to get back to hard facts, to see reality as it is and not how we define it to be or wish it could be. Petropoulos constantly made this critique of definitions and wishful logic clear, even in his poetry, whose tone varies from his characteristic melancholy to sardonic humor. “Long live contradictory definitions,” he exclaims in his early long-poem Suicide.

His later Encomium to Cicciolina includes this unsettling syllogism in which—as one of his other stylistic traits would have it—conventional transitions are conspicuously missing: “Specialists vainly seek to define the difference between Eroticism and Pornography. Definitions have a great attraction for academics. The word vagina begins with a V (like victory).” And consider this neo-Cartesian maxim from his first book of poems, Funeral Oration: “I contradict myself, therefore I live.” Ultimately, Petropoulos applies his trenchant skepticism about definitions to the definitions and self-definitions that he himself formulates. This is what he avows in After: “I see the Truth in others; / I am cross-eyed in front of my own Truth.”

You also had a book of poems translated and published in Greek last year titled Finistrinia / Portholes (Koukkida Editions), which is related to the “decisive journey” which initially brought you to Greece for a year in 1976-1977. Tell us a few things about this experience as imprinted in the book.

Portholes, which was translated into Greek with great care by Spyridoula Varvaringou, is a single sequence of short poems originally conceived as a livre d’artiste with the French artist Caroline François-Rubino. When I met her in 2014, she gave me the pdf’s of a series of paintings, titled Portholes, which she had based on the real portholes that her brother, who has long lived in Greece, had collected over the years. The paintings suggested a sea voyage, glimpsed from behind portholes. When I examined the paintings more closely, mental images associated with my own ferryboat trip, from Piraeus to the island of Samos in the summer of 1976, immediately surged forth. I was able to reexperience the voyage, as if through a process of Proustian recollection.

Shaping my fragmentary memories into fragmentary verse, I begin writing the sequence, which narrates, through thoughts and sense impressions, a half-diurnal, half-nocturnal voyage across the Aegean, as the slow boat glides past islands along the way. This journey was “decisive” in that I made up my mind, during that ferryboat ride, not to return to the United States, where I was supposed to resume my academic studies. I realized that I could at last give myself over fully to my long-time secret passion: writing. None of this is mentioned in the poems, which are narrated in the second-person singular to an unnamed “you,” but such is the invisible autobiographical backdrop to a life-changing journey. The book, which has also appeared in French, Italian, and Serbian editions with the original illustrations, as well as in a longer American volume comprising other sequences, aims at evoking a passage through time, and space, during which a life, any life, can be radically changed.

In the words of the publisher, it’s a “poetic sequence, with its dichotomies of light and darkness, of presence and disappearance, with its questions about the passageways -the portholes- between inner and outer worlds”. Which are the main themes the book delves into?

The essential themes of the poems are philosophical, or existential, but not explicitly autobiographical. A human being is—“you are”—in a boat faring forward. The porthole, through which you gaze, offers the ideal, somewhat mysterious passageway between your inner world and the world outside; through the porthole, as the boat progresses to the distant island, upon which you have never set foot, you observe elements in the outer world coming into being and then vanishing, which is one of the fundamental laws of existence. During the long journey, which takes place over a period of about twenty-four hours, darkness slowly yields to light, and vice versa; and the ending, after an earlier positive note related to the life-changing decision, is ambiguous:

you knew

new night would

encircle

day breaking

ever less lit

You have published thirteen collections of stories, short prose, and poetry so far, while your books, essays, poems, and storieshave appeared in a dozen other European languages. How did your involvement with literature and writing begin? Which remains your driving force?

As I have mentioned, my involvement with writing began as a secret passion going back to my adolescence in Des Moines. For a long time I dared not speak of it to anyone. Although I was already an avid reader of poetry and philosophy back then, and especially—tellingly—foreign literature in translation, I initially studied mathematics. When I arrived on the island of Samos, my first Greek discovery was the poetry of C. P. Cavafy, in the Keeley-Sherrard version. His poetry gave me the impetus to imitate him by writing poems similar to his historical poems, but based on the lives of my American Puritan ancestors and various American historical events. Those early poems were hardly worth keeping, but they were followed by my “apprenticeship” with Petropoulos a year later. Our work together provided an essential driving force, all the more so in that his personality, so different from mine, even at antipodes from mine, helped me, through a kind of benevolent opposition, to find my own literary style and sensibility.

In this same Greek context and at the same time in Paris, I must also mention Elias Papadimitrakopoulos, whose concise, incisive, and ever-moving short stories were first given to me by Petropoulos (who, by the way, also encouraged me to discover the poetry of younger poets, such as Veroniki Dalakoura and Manolis Xexakis, both of whom I later translated). In 1992, I ended up translating Papadimitrakopoulos’s first two books, Toothpaste with Chlorophyll and Maritime Hot Baths, a translation reissued in 2020 by Coyote Arts. Papadimitrakopoulos’s narrative approach, used in his stories about his hometown of Pyrgos, liberated me from the strictures of the classical American short story and led me to the allusive, open-ended prose form that I adopted for my own first two books, mostly set in my hometown of Des Moines: The Presence of Things Past and Mysteries of the Body and the Mind (republished in 2020 by Red Hen Press). My debt to Papadimitrakopoulos is also very great.

Being a translator as well, most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this respect, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

Every foreign book, indeed sometimes every poem or poetic prose text in the book, has its own more or less prominent particularities, not only with respect to language (diction, allusiveness, tone, polysemy, factuality, abstraction, etc.), but also with respect to formal structural elements such as prosody, punctuation, grammar, enjambment, and what might be called progressive semantic openness or closure (whereby the ultimate meaning remains intentionally incomplete, open to various interpretations, or instead tends to sum itself up at the end, as in some of Petropoulos’s aphoristic verse in After and Never and Nothing). As a translator, my goal is to grasp these internal ingredients of the foreign text, and how they work together, and then let them, not my own preconceived intentions and, even less so, my own literary style, guide me while I am translating.

In a word, I try to remain as close as possible to the spirit and detail of the original text, all the while producing a poem or a prose text that reads clearly and idiomatically in English. I do not try to offer my own “poetic” or “free” interpretations, two adjectives that make me smile whenever I come across them in a book review about a translation. My ideal is for the foreign poet, in this case Elias Petropoulos, to speak in English as if he were an English-language poet with, however, his same personality and “tone.” This remark obliges me to qualify what I have just said. There are situations in which a little “xenity” and stylistic idiosyncrasy should, in my view, be left in the translation. The easiest examples to cite are lexical. Some words, like “mangas” or “rebetika,” are not really translatable because of their rich cultural connotations. The more subtle, difficult translating decisions involve stylistic and compositional oddities. For example, Petropoulos’s long poems and his prose (be it in his poetic texts or in his folklorist studies) are sometimes provocatively marked by a lack of transitions between sentences or between lines of verse. Faced time and again with this characteristic compositional trait, I decided long ago, indeed back in the 1980s, not to “smooth out” his style by adding my own semantic or syntactic connectors, even when I was tempted to do so. Petropoulos wrote like that: one fact, image, or thought sparks another one that might not initially seem to a reader (let alone a translator) to be related to it.

But these stylistic leaps, albeit in strange ways, do link up the two seemingly disparate elements or propositions. At the minimum, the hop, skip, and jump over conventional logic is funny. It is this deep, initially invisible, connection that constitutes one of the most remarkable features of his style. It constitutes his “poetics,” as it were, even in his prose. If we learn to appreciate these “poetics” on Petropoulos’s own terms (and he always insisted on being read on his own terms), then we can better perceive the “poetry” even in his most austere, hyper-realistic evocations of daily facts. Moreover, this trait, and not only the contents of his texts, can teach us how we might perceive reality more acutely. I am quite sure that Petropoulos’s style is intimately associated with what he learned from his own mentor, the writer Nikos Gabriel Pentzikis: “Pentzikis showed me how to use my eyes. Slowly but surely I learned how to see things askew, diagonally, illogically, axonometrically, unorthodoxly.” In my translation of Petropoulos’s poetry, and in my memoir about working with him, I attempt to pay tribute to him for the many similar lessons that I received.

*Ιnterview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE