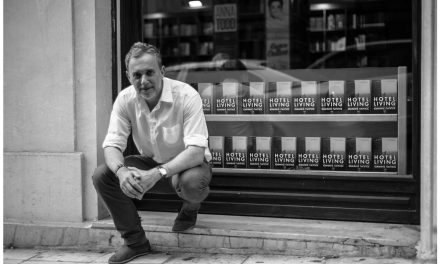

Jose Antonio Moreno Jurado was born in Seville in 1946. He is a poet, essayist and translator of Byzantine and modern Greek prose and poetry in Spanish. He taught modern Greek and Byzantine literature at the University of Seville for five years. He is an ardent researcher and translator of the works of major Greek poets Odysseus Elytis and George Seferis. He has published more than twenty poetry collections and literary works, as well as studies and essays on Modern Greek poetry and literature.

In 1973 he was awarded the Adonáis Poetry Prize for his work Ditirambos para mi propia burla and, in 1985, the Juan Ramón Jiménez International Poetry Prize for his book Bajar a la memoria. In 2019 he was named an honorary member of the Thessaloniki Writers’ Society, while he is also an honorary member of the Literary and Critical Group of Cyprus since 2020 and the Hellenic Authors’ Society since 2021. In 2021 he received the ‘Thanasis Nakas’ Award for his life’s work, within the framework of the Jean Moreas Awards.

Your multifaceted work on ancient Greek, Byzantine and modern Greek literature is so extensive that you could be rightly described as a major ambassador of Greek Letters to the Spanish-speaking world. What triggered your interest in the study of the Greek language and more specifically the Greek literature?

I started learning Modern Greek before finishing Classical Philology at the University of Seville. At a time when we had no teachers, grammars or dictionaries.

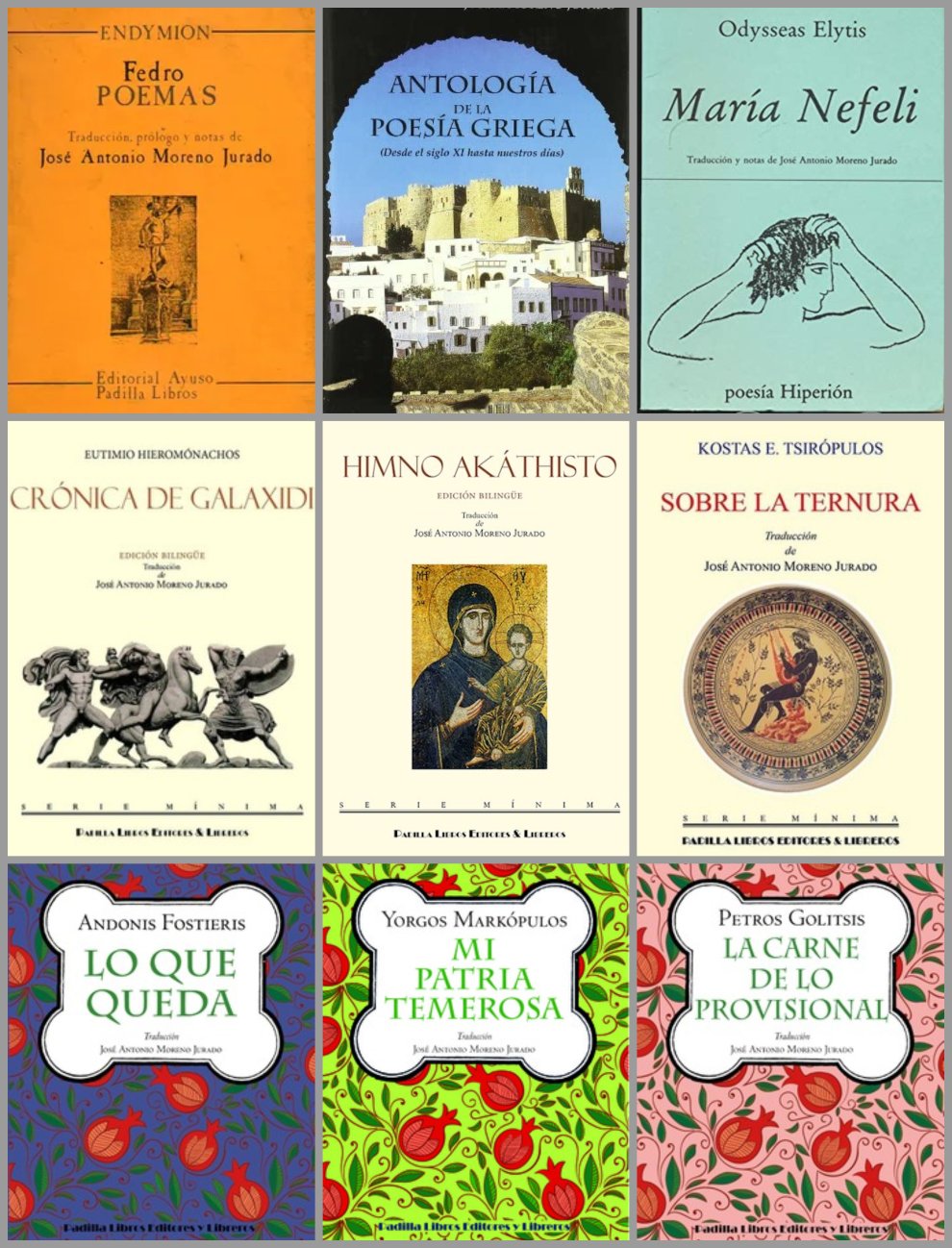

It was then that I took my first trip to Athens. In the window of a bookstore in Solonos, I noticed the cover of an exquisite book. It was just a photo of a girl naked from the waist up; with her back turned and her head slightly tilted. Her hair was quite long, very dark, almost velvety, gently curled in very specific places. I had no choice but to walk into the bookstore and buy it. Just for the cover. I could easily read its title, Maria Nefeli, although I didn’t know what it meant, and the name of the author, Odysseus Elytis, a complete stranger to me.

Since then, I have bought a thousand books, so many suitcases loaded with books and magazines. A few months later, I presented my study on Elytis and my PhD thesis on Seferis. These were my first two studies dedicated to modern Greek literature at the University of Seville.

Some of my fellow students, serious university professors today, used to tell me every time they met me: “You’re crazy if you continue to deal with modern Greek literature. You won’t achieve anything. Moreover, in the Greek language, there is no more literature and thought than that of the classical authors. Don’t waste your time on such nonsense.” Fortunately, these perceptions have changed in Spain over the years.

With the help of Elytis, I finally translated Maria Nefeli, which was published in Madrid. Over time, there followed translations of the classical era (Plato, Aristotle, Aristophanes), of the Byzantine era (Prodromos, courtly literature, Romanos the Melodist, The chronicles of Galaxidi, the Akathist Hymn), of Cypriot literature (Petrarchism), of the Cretan Renaissance (Εrotokritos) and of most recent times (first and second post-war generations, and a 800-page poetry collection from XI century to the present).

That is, a whole life dedicated to Greek literature.

A poet, a researcher, an essayist, a translator. Where do all these attributes meet? Would you say that love for language and culture is the binding thread?

How such an extensive and persistent work be explained if not for my love for the language and culture of this people. First of all, because language, as Seferis used to say, is the same in essence from Homer to our days, although it has obviously suffered the changes of times and has undergone different natural phases. A language in constant motion, always alive, like life itself. A language in endless development. And this has always fascinated me.

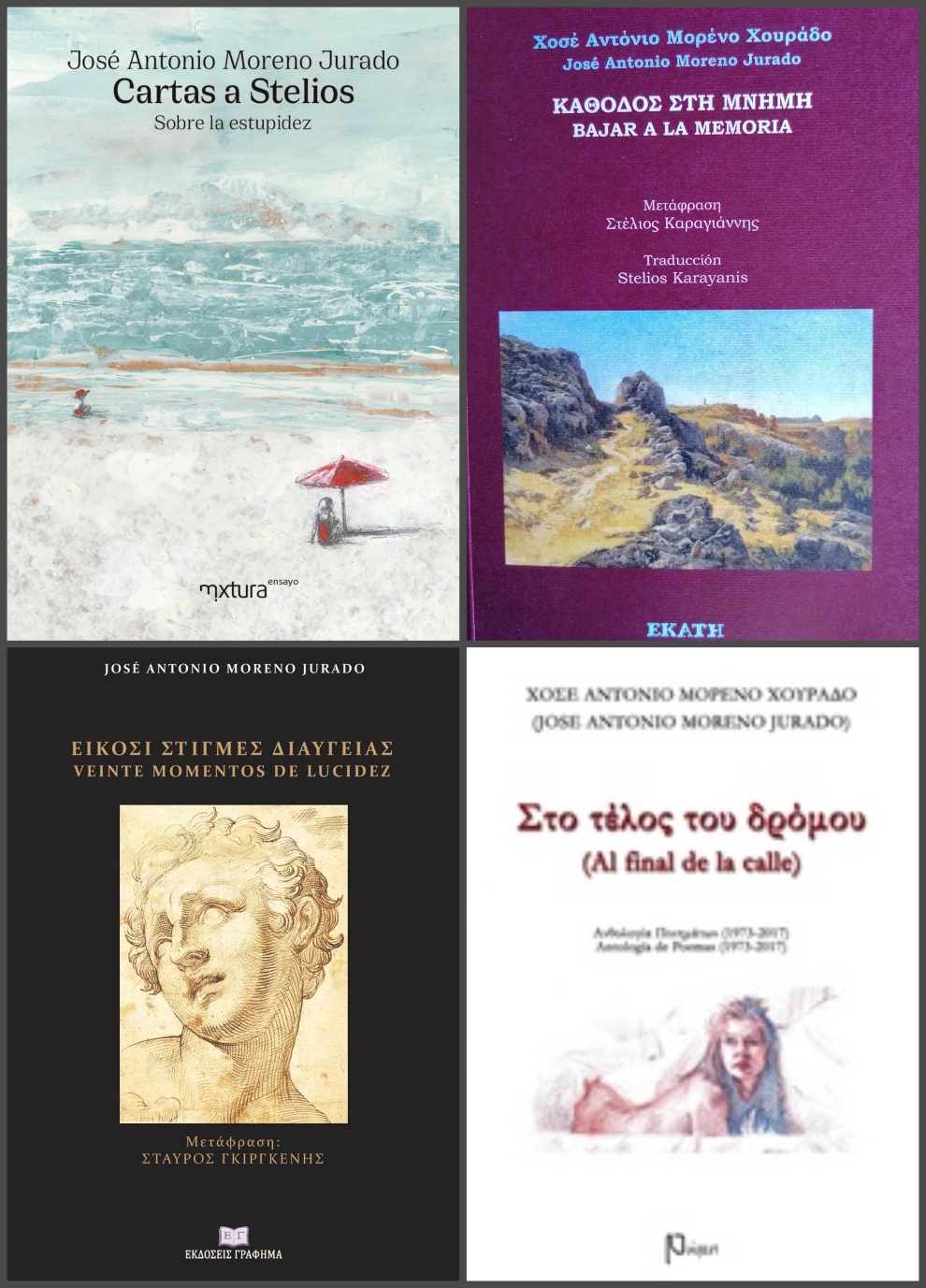

Your latest writing venture, the bilingual anthology titled Κάθοδος στη μνήμη – Bajar a la memoria was recently published by Ekati. Tell us a few things about the book. More generally, which are the main themes your poetry delves into? Would you say that your poetry bears the influence of both ancient and contemporary Greek literature?

In 2008, a collection of my poems titled At the end of the road was published in Thessaloniki by Romi Editions, translated by Stelios Karayannis, Anna Stergiou, Stavros Guirgenis and Tassos Passalis. The book was presented in Thessaloniki, Serres and Edessa. In 2021, Twenty moments of lucidity was published (Grafima Editions), translated by Stavros Guirgenis. In 2022, Κάθοδος στη μνήμη – Bajar a la memoria (Ekati Books), translated by Stelios Karayannis, is a compilation of all my books. At the moment, a publication of Phaedrus is underway by Endymion Editions, translated by Vassilis Laliotis.

I must confess that there are two clear influences in my poetry: on the one hand, my own tradition, which I learned and read steadily from my youth; on the other hand, the Byzantine tradition and of course the teachings of Elytis and Seferis. The first taught me the way of image and metaphor, very close to surrealism and the dream world. The second taught me the simplicity of the poem and the seriousness. Through my own tradition, I closely followed the steps of San Juan de la Cruz, Garcilaso, Quevedo, Bécquer and the poets of the generation of 1927, that is Lorca, Alberti and Dámaso. And it was always a great pleasure to read the work of Juan Ramón Jiménez.

You are responsible for the collection ‘El Árbol de la luz’(Padilla Books), which already comprises more than 25 books by contemporary Greek poets. Tell us a few things about this venture.

‘El Árbol de la luz’ isaseriesof small books published in Seville by Padilla Libros. A series dedicated to modern Greek poetry. More precisely, a poetry written in Greek. I am the only one who translates the poets and we have already published 25 books. They all have the same look and only the color of each book changes. Poets of Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, Larissa, Tinos and Cyprus.

Yet, I should also mention another series, in the same publishing company, called ‘SerieMínima’. There were published The Akathist Hymn, The chronicles of Galaxidi, On tenderness by Kostas Tsirópoulos, Α walk around Seville by Kostas Ouranis, The Gospel of Thomas, and two contemporary female poets, Zosi Zografidou and Liana Sakelliou.

Are there literary ties that unite Greece and Spain? In this respect, how important is the role of translation in the dissemination of a literature beyond national borders? In general, could translation contribute to a better understanding between cultures and translators act as cultural ambassadors between countries?

I cannot, nor dare, call myself an ambassador. I’m just a man who loves his job. And I am only trying to create a rapprochement between two literatures that have many elements in common. There is still a lack, in the field of comparative literature, of serious studies about the two cultures. For my part, I only want to build a bridge between two cultures. But Idon’t know who will walk on it.

I prefer not to touch on other issues related to our contemporary world. For instance, who and how many people read poetry today in Spain and in Greece. That’s why governments need to pay very close attention to education.

I clearly remember, when I accompanied Elytis on his visit to the House Museum of Juan Ramón Jiménez and later to La Rabida (from where Christopher Columbus set out for America), how the poet, leaning against a huge window facing the sea, told me in low voice, “This sky, so dazzling blue, is also the sky of Greece”. And now I myself add, “What about poetry?”

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE