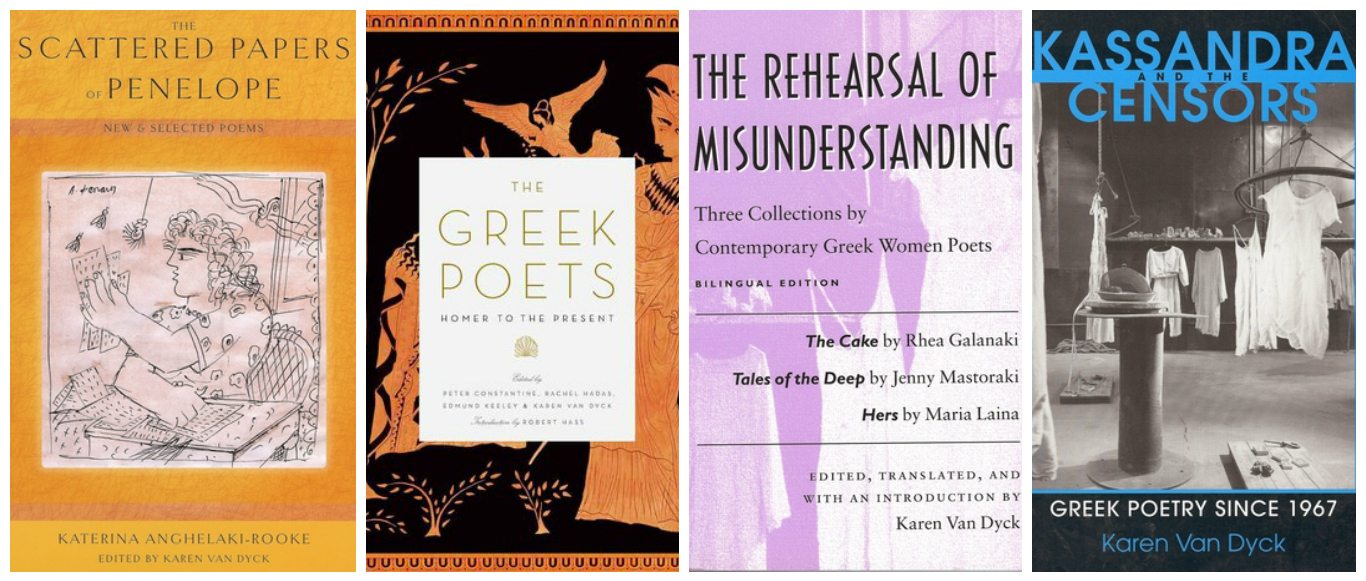

Karen Van Dyck is Kimon A. Doukas Professor of Modern Greek Literature in the Classics Department at Columbia University where she created the Program in Hellenic Studies. Her books include Kassandra and the Censors: Greek Poetry since 1967 (Cornell, 1998; Agra, 2002), The Rehearsal of Misunderstanding: Three Collections by Contemporary Greek Women Poets (Wesleyan, 1998), The Greek Poets: Homer to the Present (Norton, 2009), and The Scattered Papers of Penelope: New and Selected Poems by Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke (Graywolf, 2009), a Lannan Translation Selection.

Her bilingual anthology Austerity Measures: The New Greek Poetry (Penguin, 2016; NYRB, 2017; Agra, 2017) was chosen by the New Statesmen as pick of the year, the Guardian as poetry book of the month as well as by Andrew Marr for his BBC Start the Week. Recent articles of hers on Cavafy – “Forms of Cosmopolitanism” and “Translating a Canonical Author,” have appeared in the LARB (2014) and Teaching Translation: Programs, Courses, Pedagogies (Routledge, 2016).

Karen Van Dyck spoke to Reading Greece* about Austerity Measures: The New Greek Poetry, noting that “the project was about mapping poetry scenes – a what’s where, rather than a who’s who”, focusing on “the most salient feature of this new poetry – its multiethnic, multilingual cosmopolitanism”. Asked about the role of poetry in times of crisis, she discusses that “given the recent resurgence of separatisms –Grexit, Brexit, Trump’s wall – the message is only more urgent now. We need poetry, and poetry in translation, to tell us things we can’t know otherwise, and if we don’t pay attention, it is at our own peril”.

As for translation, she comments that “the translator of contemporary poetry has to think beyond national boundaries in the same way the critic must work to undo the sense that literature is a national institution that obeys the rules of one language”, and concludes that “it is up to translators, but also the minor cultures themselves to get their literature out there through astute marketing that is informed by knowledge of the receiving cultures. Anticipating the impact of a translation in the receiving culture is a way to take responsibility for the translator’s work, something that translators as well as publishers need to do”.

Austerity Measures gathers the very best of Modern Greek poetry. What’s the story behind the book? Has the crisis rekindled the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry?

Yes, definitely. Both in the UK and the US readers are interested in Greek poetry again. The Guardian has been posting interviews with Greek poets and now the NYRB blog has invited them to read their poems and post videos of themselves.

The story behind the collection is quite simple. Reading and writing about Greek poetry for over thirty years I was wowed by the intensity of artistic output in the wake of the recent crisis. It was unlike anything I had seen since the Dictatorship. Like then, the strong presence of women poets was palpable. The poems being written were poems I felt needed to be translated, poems that had something to say to a larger audience outside Greece.

Though I first imagined “Austerity Measures” as a title in English, its appropriateness was clinched when the editor of the Greek edition Stavros Petsopoulos also saw its potential “Μέτρα λιτότητας” (Metra litotitas), both a term imbedded in the political discourse of the times, yet also deeply poetic. It could challenge the strict divide between disinterested belle lettrism and engaged social realism that has prevailed in Greece. At so many different levels, then, the anthology is about translation. Going back and forth between languages, between poets and translators, editors and publishers, and so forth.

“What most distinguishes the poetry of this new millennium from that which came before is, on the one hand, its diversity – there are no clear-cut schools or factions – and, on the other hand, the cultural conditions that it takes for granted”. Could you elaborate on that?

I was most surprised by how so many of the new poets I was discovering had no idea what other poets were doing. The poetry magazines and small press publications in piles on the floor of my office at Columbia University in New York City – Poiitiki, Pharmakon, Teflon, Poiitika, Shakespeirikon – belonged, on the one hand, to separate spheres, but also, on the other hand, had important overlapping concerns. The anthology was an attempt to mix up the piles and put everyone into conversation. I chose poems and translations, not poets or translators. The project was about mapping poetry scenes – a what’s where, rather than a who’s who.

Anthologies are always about the art of ordering, bringing out an argument by grouping certain texts together. I focused on what I consider the most salient feature of this new poetry – its multiethnic, multilingual cosmopolitanism – and then went for examples that showcased how something we usually think is destined to be lost in translation can actually be a way of connecting up disparate traditions – formal issues such as line length, the shape of a poem or issues of literary tradition and convention such as intertextual references, proper names, linguistic register and codeswitching.

Initially I thought about putting the less known online poets like Jazra Khaleed and Kyoko Kishida first so as to shock readers out of any expectation of Greek clichés like marble columns, sea, and sun, but my editor at Penguin relayed an interesting observation: most readers, he said, thumbing through books of poetry in bookstores, open to the middle. This is where you can catch them by surprise. So I kept to my plan to start in Athens with established literary magazines, and then move to the more offbeat literary collectives, from there to online poetry, then to poetry in the provinces and on the edges, and finally by migrants inside Greece and Greeks outside scrambling the borders of what counts as Greek poetry altogether.

What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits? What can it mean for poetry to be political, or apolitical, in times of social and economic crisis? Can poetry actually offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Only after the anthology was finished did it become clear to me how the drama of borders, migrants, and a sea impossible to patrol, now so much in the news, had emerged in Greek poetry some time ago. Literature often tells us what will happen before it happens. Poetry, more than other genres, plays the role of a Cassandra. What is striking is how the soothsaying in this poetry involved upending an older model of disinterested modernism. It insisted on talking about the troubles, however indirectly. It wasn’t possible to let boatfuls of migrants drown or to build barbed wire fences and detention centers without serious repercussions for everyone. Given the recent resurgence of separatisms –Grexit, Brexit, Trump’s wall – the message is only more urgent now. We need poetry, and poetry in translation, to tell us things we can’t know otherwise, and if we don’t pay attention, it is at our own peril. As William Carlos Williams says in the epigraph to the anthology [#34], “It is difficult to get the news from poems/ yet men die miserably every day/ for lack/ of what is found there.”

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie?

I think the translator of contemporary poetry has to think beyond national boundaries in the same way the critic must work to undo the sense that literature is a national institution that obeys the rules of one language. But on this count the translator may have a head start since she already knows her translation is de facto divorced from the source language. It comes as no surprise that everything is up to her now. It is her responsibility to make it make sense for a new audience in a new way.

In her article The Making of Originals: The Translator as Editor, Karen Emmerich notes that when translating from a so-called “minor” to a so-called “major” language or literature, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power? Can translation ever be unethical?

Translators in any language when translating into any language wield the power of interpretation in their work. It is not more so when translating into a major language or when translating a minor literature. The specific situation determines the nature and function of the power. Translation everywhere is a cultural practice with far-reaching social effects. The question is how the translator takes responsibility for this power.

Translation is always about the possibility of a second, third, or fourth translation and never about a single, authoritative translation. Yes, often this doesn’t come to pass given the unequal distribution of cultural prestige and capital, but the ethical charge, if you will, must always imagine it is possible and fight for it. An ethical translation is one that understands the conditions of its own production and makes that visible. It is one that is open to different interpretations. Here I think translators and publishers and reviewers in the target language can do a huge amount to educate readers about how to read translations, but I also think authors, publishers and reviewers in the source language need to think beyond literature as a national institution.

In an interview you did with Theodoros Chiotis I noticed with interest his plug for a more consistent state policy for translation. The problem, of course, is whether the people deciding what gets support know enough about the international publishing scene. Other minor literatures such as Catalan have a better record of supporting not only the translation, but also the dissemination of Catalan literature abroad. The Greek Ministry of Culture would need to work with foundations and international groups of scholars and writers in the countries where the literature is being translated and published. Not every translator or press in a major culture can offer strategic help in supporting a minor literature, some, for example, are in the business of ghettoizing the literature in an appeal to one readership such as Greeks of the Diaspora. It is up to translators, but also the minor cultures themselves to get their literature out there through astute marketing that is informed by knowledge of the receiving cultures. Anticipating the impact of a translation in the receiving culture is a way to take responsibility for the translator’s work, something that translators as well as publishers need to do.

What about books that are written between two or more languages? What does a translator do with texts that are already translational? How demanding is it to translate Diaspora and immigrant writing that doesn’t belong to one national canon?

Many critics think it is impossible to translate multilingual literature, but I prefer to view it as a resource for translation. Multilingual literature with its high coefficient of creole and hybrid idioms (Gringlish, Gritalian, Gralbanian) challenges the prevailing assumption that languages and cultures are discreet entities. If originals cross borders and share common words, syntactical structures and referents, then surely translations can too. Multilingual practices in the source text map out ways for translators to be more experimental by exposing the instability and ideological import of their own language. That can only help readers become more aware of the linguistic and cultural conditions of minority—in every sense of that word.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE