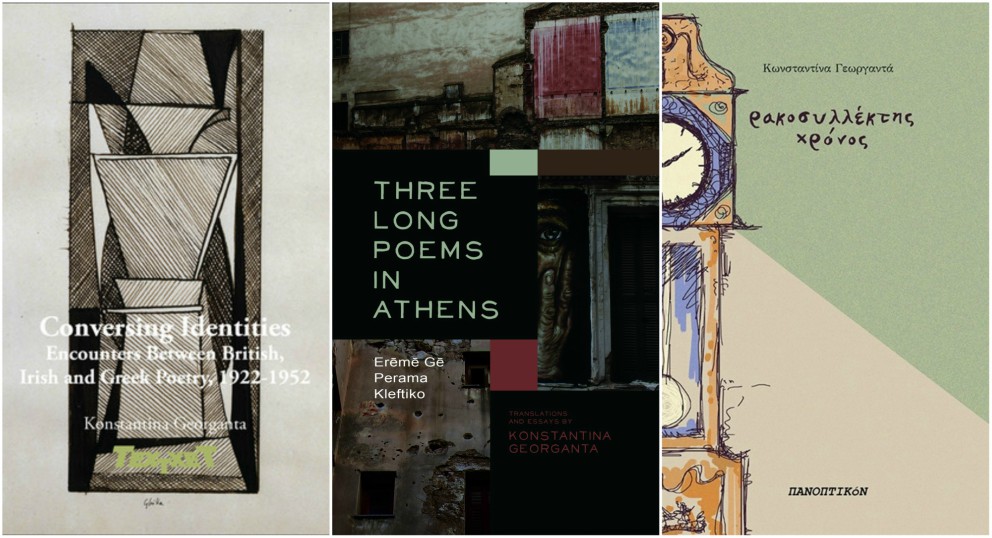

Konstantina Georganta is the author of Conversing Identities: Encounters Between British, Irish and Greek Poetry, 1922-1952 (Brill, 2012) and Three Long Poems in Athens: Erēmē Gē-Perama-Kleftiko. Translations and Essays (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2018). Her first poetry collection, Rakosyllektis Chronos, was published in 2015 by Panoptikon. She manages athensinapoem.com, a website dedicated to the collection of material on urban poetics about Athens, and akindofclock.com, where one may find a world of Greek poetry into English. She studied English Language and Literature at the University of Athens and twentieth-century literature and literary movements at the University of Glasgow, where she also completed her doctoral thesis at the Department of English Literature.

Konstantina Georganta spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest writing venture Three Long Poems in Athens: Erēmē Gē-Perama-Kleftiko, which unfolds in the city of Athens, noting that “this return to the inescapability of predetermined lives ever haunting the scene is a common element in all three poems”, “an element which in turn transforms Athens into the centre of ‘meta-politics’, which is the realm of literature”. She also talks about ‘Athens In a Poem’, “a website dedicated to the collection and dissemination of material on Greek urban poetics”, as well about its sister page, ‘a kind of clock’, which aims to “gather as many material as possible in one place so that Greek poetry may become increasingly available to an international audience”.

She elaborates on the term ‘urban poetics’, which refers to “poetry’s reaction to the urban environment”, adding that her aim is “not only to create a collection of urban Greek poetics but also to make these a common currency to the general public”. She comments that “literature helps readers envision alternatives to seemingly inescapable realities by sparking the imagination in unexpected and creative ways”, and concludes that “in order for the word of Greek poetry to reach wider audiences we need to draw parallels to the poetry created elsewhere and it is here that the work of modern scholars and translators is extremely significant”.

Your latest writing venture Three Long Poems in Athens: Erēmē Gē-Perama-Kleftiko unfolds in the city of Athens creating a thread linking the 1980s to 2010s. Tell us a few things about the book.

Athens is an emblematic city, a place of significance. It is memory embodied in a multi-layered topos, a place of ruins with the Parthenon as its headpiece. The routes one may follow in the city are numerous and the story one may narrate changes with each turn one takes. Three Long Poems in Athens: Erēmē Gē-Perama-Kleftiko acknowledges this and offers something different. Here is the option of the poetic word creating narratives that travel through the city of today but also cut into the city’s past touching on various of its corners and opening up to the readers the city’s microcosm yesterday and today. Through this itinerary, the city becomes emblematic of the macrocosm surrounding this city and others like it.

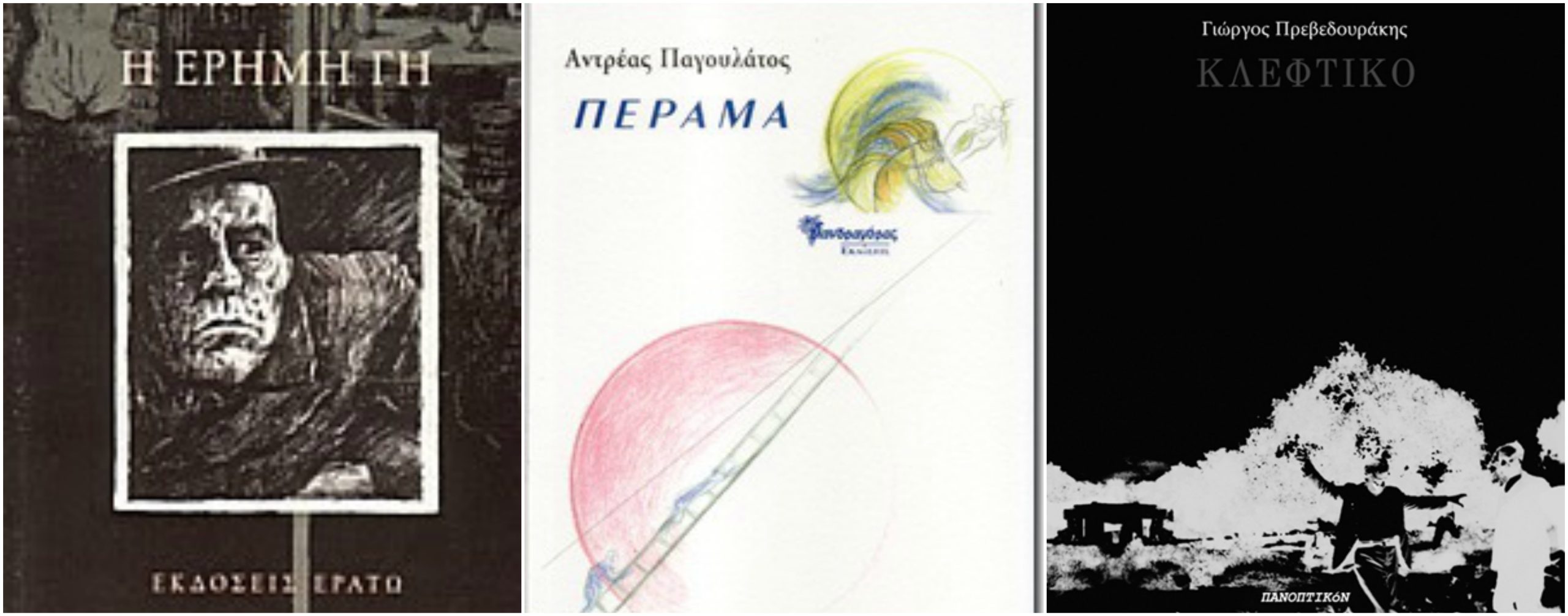

This book includes the first translation of three Modern Greek poems into English with an equal amount of texts unraveling their significance to a foreign audience. The reader is led from Kaisarianē, the corner Patēsiōn-Stournara, Athēnas street, Concordia Square and Monastēraki (Ēlias Lagios, Erēmē Gē, 1984), to the old harbor and refugee suburb of Perama 14.7km from the centre of Athens (Andreas Pagoulatos, Perama, 2006), to Psyrrē, Exarchia, Agioi Anargyroi and Kypselē and finally into all the bins of Athens (George Prevedourakis, Kleftiko, 2013). The critical texts accompanying the poems urge readers to view the poems as historical meta-texts, city narratives and depictions of the ‘meta-hellenic’, active political texts offering valuable insights into today no matter from how many years afar. This is why all three poems dwell on the pseudo opposition between the ‘here and now’ as opposed to ‘there and then’ dragging the past into the present and making the news of the past relevant again to the world today in what poet and critic Gerasimos Lykiardopoulos named the true dynamic of the ‘resistance of poetry’.

Starting from the ‘the deforming of man’, foretold in Erēmē Gē as a tortured ‘repetition’, the story moves on to the ‘extermination / of the humble / the outcasts / the predetermined’, all ‘victims / sacrificed / by the voracious / vicious money’ in Perama and the event that ‘has already happened / before it has’ in Kleftiko. This return to the inescapability of predetermined lives ever haunting the scene is a common element in all three poems, whether the place is called ‘Erēmē Gē’, ‘Perama’ or Kleftiko’s ‘Fevgada’, an element which in turn transforms Athens into the centre of ‘meta-politics’, which is the realm of literature. As Jacques Rancière notes, ‘the principle of that “politics” is to leave the common stage of the conflict of wills in order to investigate in the underground of society and read the symptoms of history.’

The poems address one’s ability to judge events and so form an opinion (in Greek, ‘krisis’) as based on one’s comprehension of these events and access to them. This most significant to society ability of ‘krisis’ is part and parcel of the origin and goal of the poetic text, itself part of the complex cultural object that is public speech. The poetic text sorts out events so as to amplify one’s ability to express an opinion. Irrespective of ‘crises’, then, the main goal of the poetic text is ‘krisis’. Indeed, Kleftiko attests to this with its epigraph, which addresses the conundrum of the formation of an opinion as dependent upon the degree of one’s comprehension of events: ‘No matter how we were told they will hear us otherwise / No matter how we were written they will read us otherwise’ (Vyron Leontarēs).

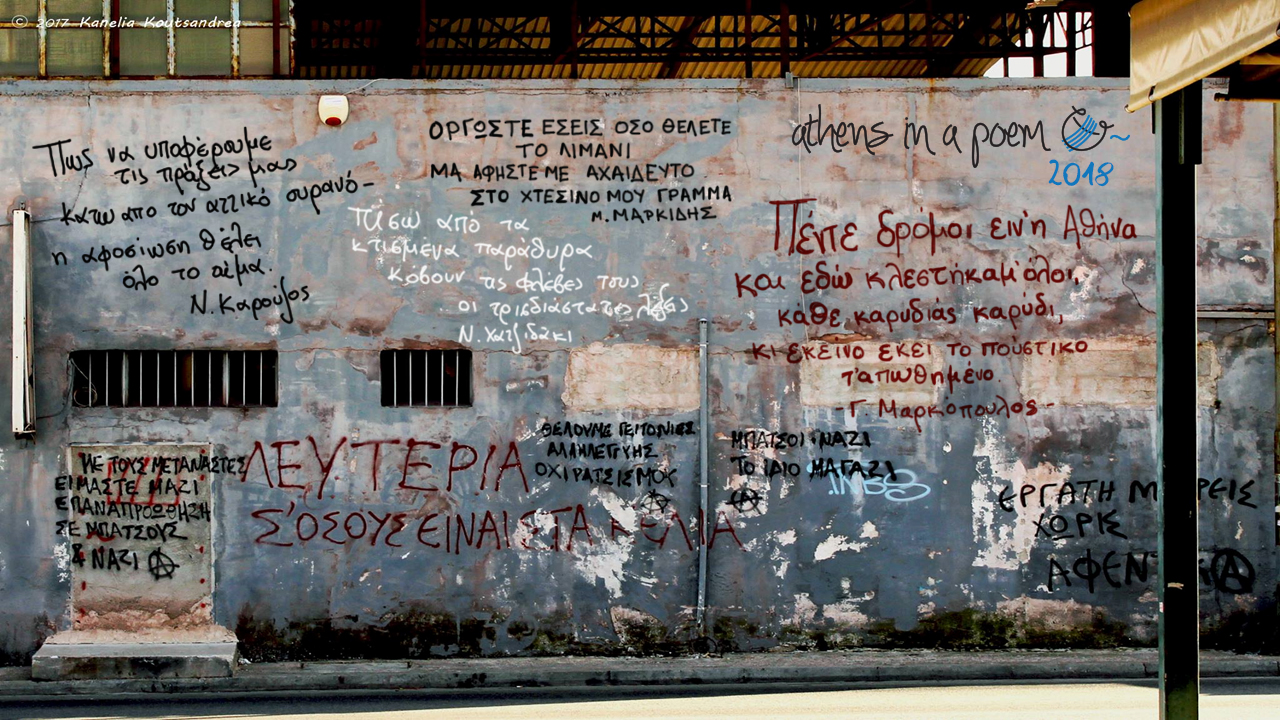

Athens In a Poem focuses on the Athenian urban experience with a presentation and examination of poems, photographs, the relationship of words with space and short texts on what makes and breaks memory in the city. What’s the story behind this pioneering venture and its sister page a kind of clock?

Five years ago, in May 2014, architect Kanelia Koutsandrea and I created athensinapoem.com, a website dedicated to the collection and dissemination of material on Greek urban poetics but also a space where we could gather different narratives that make and break the memory of the city. We share a common interest in literature, architecture, cultural and critical studies as well as the anthropocentric dimension of the urban space with a focus on time, collective memory and urban decay. The website was the outcome of long discussions on the lack of a collective consciousness of the city as imagined from within by its own inhabitants. Urban poetry was combined with architecture and urban narratives to create an imaginative map of the city of Athens which would in turn make the city’s inhabitants imagine living in this beautiful palimpsest but also aid the city to become itself. Each post we publish on our website is then disseminated via social media and the public’s interest has grown gradually throughout these years.

Taking this endeavor a step further, a volume titled Athens in Poems: An Imaginative Map of the City (forthcoming by Ekdoseis ton Synadelfon/The Colleagues’ Publications) aspires to function as an alternative travelogue to the city via 34 poems in English translation covering the period 1880s to 2010s. The starting point chosen reflects an important moment in the city’s development for, even though the establishment of Athens as a capital in 1834 had instigated a large inflow of new residents, it was only at the end of the 1880s that the milestone of 100,000 residents was passed. A city designed to be an administrative and not an industrial center – a role adopted by the neighboring city of Piraeus – was slowly emerging and the poem that opens the volume, written by the well-known satirical poet Georgios Souris, captures this still awkward moment in a city still growing. It suffices to mention that until roughly the 1880s the limits of the city remained essentially those of the Old City, with areas such as Omonia, which are today the center, remaining nearly deserted. With this in mind, readers are urged to walk through the streetscapes of Athens, reflect on the city’s historical development and see how poetry becomes attentive to the dynamic instability of the urban space. They are offered the opportunity to wander around Athens of the 1880s, imagine the circular Omonia Square of the 1930s, visit the Shooting Range of Kaisariani during the Nazi Occupation, reach the gate of the Polytechnic School in the 1970s, look at the capital as a huge fish tank in the 1980s, discover the bastion of Kokkinia, get to love the city’s concrete block of flats and pause for a while to have a glass of ouzo at the Athens Railway Station.

The sister page akindofclock.com counts only a year of life and is the outcome of my interest in poetry and the translation of Greek poetry into English. It owes its name to the idea that the translated text is a kind of clock conflating time and space in the poetic universe. The poetic text in translation is a time capsule transferring important information to the present day and also a form of memory as language is revisited to unveil the meaning of the text in a context different to that in which it was initially created. The website aspires to present ‘A world of poetry from Greek into English’ measuring life one poem at a time. On it one may find poems, book reviews, essays on translation and a library with a list of Greek poetry in English translation. The aim is to gather as many material as possible in one place so that Greek poetry may become increasingly available to an international audience.

Could you elaborate on the term ‘urban poetics’? What is the relationship of poetry to the world it inhabits?

‘Urban poetics’ is about poetry’s reaction to the urban environment. It includes poems about the experience of the city, an exploration of the linguistic mechanisms used to reflect this experience and the way in which the language cities are built with, that is, the language city inhabitants hear or see around them in the city, is recorded in poetic form and so elevated into a symbol about what is hidden behind our everyday routines. This is a site hugely unexplored when it comes to Greek poetry even though poems talking about the urban experience have a history as long as the cities we inhabit. My aim is not only to create a collection of urban Greek poetics but also to make these a common currency to the general public. This goes hand in hand with my view of poetic texts as significant historical, political and cultural documents, pieces of imagination which can extend personal and public awareness by recording and preserving elements of the culture and human geography of their time and place. I read poems as political texts exposing the world as being insufficiently defined and thus expanding a seemingly monolithic way of knowing not only the city but ourselves and the world at large. A poetic line is not simply a catchphrase to use when words appear to betray us, it is the world imagined anew one word at a time.

Could poetry help debunk stereotypes and offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Literature helps readers envision alternatives to seemingly inescapable realities by sparking the imagination in unexpected and creative ways. Poetry is one such unexpected and creative means of envisioning something new and it does so with the commonest of everyday tools: language. Through the poetic form language is stretched, weighed, unshackled, transformed, led to breed meaning anew. Now, if it is by naming things that we exercise power over them, then poetry is liberation from the process that says this should be so and so. And so with stereotypes. If you expose the falseness of a certain belief, then a stereotype could be no more. Poetry has the dynamic to do that and more.

In recent years the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry has been rekindled, with an increasing number of Greek anthologies being translated in English. What is it that makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

A foreign audience needs to be trained into welcoming a poetry foreign to them. Greek poets have always been in dialogue with the world and there is a lot of foreign poetry translated into Greek, which has made a big corpus available to Greek readers. The bet now is to work towards the opposite direction in novel ways. Greek poetry anthologies offer visibility of a number of poets to an international audience and create a body of work in translation readily available yet we also need to have this work creatively juxtaposed with the work of other poets throughout the world so that the poetry does not remain provincial. It is in this way that it is not solely a matter of presenting one national poetry against another, which involves to a certain extent a kind of stereotyping that the language poetry represents fights against, but of showing the everyday relevance of poetry to the world today. I would like to see more collected volumes of individual poets translated so that their unique voices can be heard and linked to other voices out there. In order for the word of Greek poetry to reach wider audiences we need to draw parallels to the poetry created elsewhere and it is here that the work of modern scholars and translators is extremely significant.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE