Konstantinos Papacharalampos was born in Kavala, Greece in 1988. He holds a Diploma in Rural and Surveying Engineering from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and an MSc Real Estate from CASS Business School (London). He wrote poetry project K – On (Entefktirio ed., 2011) and took part in 1st Festival of New Writers organized by Greek National Centre of Books. His poems have appeared in leading Greek magazines and installed in situ in Action Field Kodra. He has performed poems from his second book Είναι (Íne, [FRMK] ed., 2015) in Athens, Thessaloniki (Lola Nikolaou Gallery) and London (Curious Body Soufflé exhibition) in both Greek and English.

Futures: Poetry of the Greek Crisis anthology of UK publisher Penned in the Margins featured a poem from his latest book. Other poems from his releases were translated in German and Russian and associated with financial crisis and the Greek avant-garde scene. In parallel to his poetry he works as investment manager at Battersea Power Station in London. In 2014 he was a recipient in the first RICS Matrics Young Surveyor of the Year Awards.

Konstantinos Papacharalampos spoke to Reading Greece* about his two poetry collections commenting on his “ongoing interest in creating a new language experience in every project I release, intending to explore beyond established norms”. He characterizes himself as a ‘neofuturist’ noting that “both poetry and surveying have unique abilities to summarize the bigger human picture, a picture of constant change, our common history of ups and downs”, and that what he is after is “the balance of the changes, the place where moments exist together”.

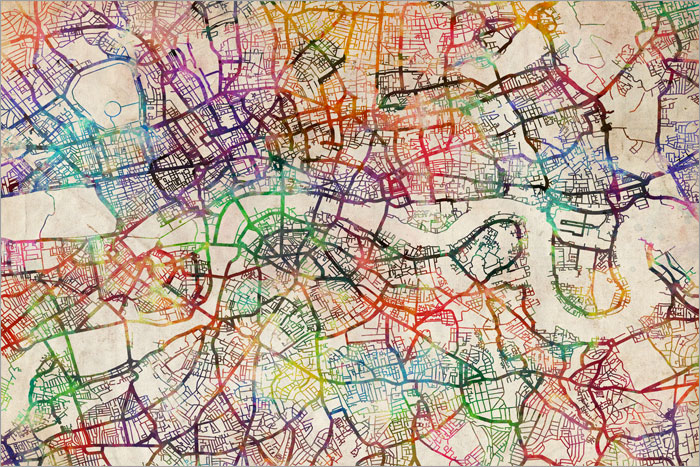

Asked about the ‘global city’ as an inspiration in his poetry and experimentations, he explains that “London would not be the same successful metropolis it is today if it wasn’t a free city, a city that is welcoming to different backgrounds, races, religions and opinions”, and expresses his uncertainty as to whether “the voice of London will alter in a post-Brexit landscape”. He concludes that “the crisis did turn more heads abroad to look at Greek poetry, especially at contemporary poetry”, commenting however that he doesn’t believe there is “a certain national identity as such to show. Each person, each poet, has his/her own identity; each one of us is different and can still be more or less proud of a home country, whatever you choose your home country to be”.

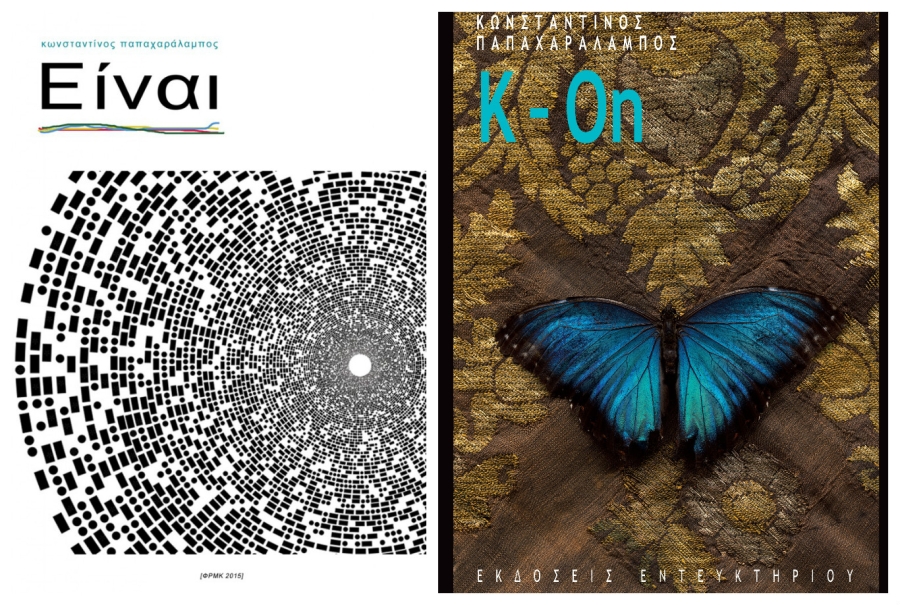

You have published two poetry collections so far: K – On (2011) and Είναι (2015). What is that differentiates the two books and what remains the same?

My first book is an interactive project on new starts, using topology, dialogue and minimalism as writing techniques in the poems – the reader is asked to navigate his/her own way to reach the ‘new start’. The presence of techno and electronica music scenes is also influential. My second book is a space grid project on life moments happening simultaneously. I explore the feeling of life and death occurring simultaneously; yes, life is what it is. In retrospect, the poems there go deeper into spiritual territory, as I built the book to be a meditation tool.

In the second book I also experiment further with asymmetric visual and sound techniques in writing; someone can hear the voice of mantras and underground disco among the lines. I saw Earth as the big disco ball and created poems with spread words and letters across the page to meditate on accepting us for what we are.

What is the same is my ongoing interest in creating a new language experience in every project I release, intending to explore beyond established norms. I believe it’s good to keep experimenting.

Futurism, Surrealism, minimalism, pop-art, optical poetry. How are these artistic movements imprinted on your work?

They are all part of what I call Neofuturism. It’s less of another –ism and more the experience of contemporary life and challenges ahead. We live in a world with huge technological changes; think of how often unique health improvements are made or new smartphones replace those released months ago. We already live in kind of futuristic, fast pace, times, where every single moment is somehow within its own sub-reality bubble. What I am after though is the balance of the changes, the place where moments exist together.

Where do we find the line of sustainability? Where do we find the balance with respect to the environment? Do we ensure technological changes go together with advances in the human conditions? Do we deepen life chances as we deepen technological changes? This is the path I am walking on. This is how I am a neofuturist. I need to make a special mention for pop-art though, as it plays a particular role in my next project. My kind of ‘pop’ is very much the focus of my upcoming third book, still part of the wider neofuturistic picture.

You have characterized yourself as a “word surveyor”, while you use contemporary visual art techniques, mapping, installation and sound to challenge norms of language. Where do surveying and poetry meet and what is their binding thread?

I believe in change. I believe in human strengths and mistakes – I want to embrace us for what we are. Both poetry and surveying have unique abilities to summarize the bigger human picture, a picture of constant change, our common history of ups and downs – there I see an upward trend and a future of opportunities. I want this future now. My language experimentalism challenges the existing, both visually and conceptually, and asks for that change – the way that the development surveying I do at Battersea Power Station is about the challenge of bringing new life to a giant industrial building which has remained derelict for 30 years.

In his review of your poetry, Petros Golitsis comments on the priority you give to language, which re-arranges the world through innovative optic and sound combinations. What purpose does language serve in your writings?

By intention, I build my writings with three main components: optics, sound and meaning. These co-exist and interact in the lines and create something which I believe is above them; that’s what a poem is about. I don’t rely solely on just one of these three components. I believe this enables my work to be translated easily into more than one language. More than this, when I perform my work the optics, sound and meaning explorations come to life in a different way as I move across the stage; I become my own poem, performed not just printed.

“The global city has always been an inspiration in my poetry and my experimentations. Starting from London, I would like to see an interactive dialogue on poetry and modern art in this era of historical change”. Tell us more

Brexit, Brexit, Brexit… What a shock. In my first book I write about reaching your goals like reaching for an apple from a tree. London was and is one of those apples. I believe in the energy of this city. We can fix those things that go wrong – and make the most out of the experience. We do need to explore more the idea of freedom and humanity – art can play its role in this. London would not be the same successful metropolis it is today if it wasn’t a free city, a city that is welcoming to different backgrounds, races, religions and opinions. I don’t know if the voice of London will alter in a post-Brexit landscape but we can use art to make more people think and remind them that division and isolation are never a good idea.

What about Greek poetry? Has the crisis rekindled the interest of Greek poetry abroad? And, in turn, could poetry be used to debunk stereotypes about the Greek national identity and contribute to the construction of a new narrative about the country?

I think the crisis did turn more heads abroad to look at Greek poetry, especially at contemporary poetry which grew in volume recently – there are already more than two relevant anthologies. Interestingly the years that led up to the crisis didn’t get such attention. I guess the world waited for the full bad news. Poetry is useful for the presence of one country though, putting it on the cultural map of the world; yes Greece is not the center of it.

However I don’t believe there is a certain Greek national identity as such to show. Each person, each poet, has his/her own identity; each one of us is different and can still be more or less proud of a home country, whatever you choose your home country to be. It can be the world too. After seven years in London I have seen heads turning when you speak honestly and objectively about what has happened in Greece. Recognizing where you really went wrong is the first step to improve things. This is the narrative I see.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE