Kostas Akrivos was born in Glafyres, Volos, in 1958. He has published novels, short story collections, and has participated in collective editions and anthologies. His novels have been translated in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Poland, and his short stories have appeared in many European languages. He was the editor of the series A City in Literature by Metaichmio Publications and teaches modern Greek in secondary education.

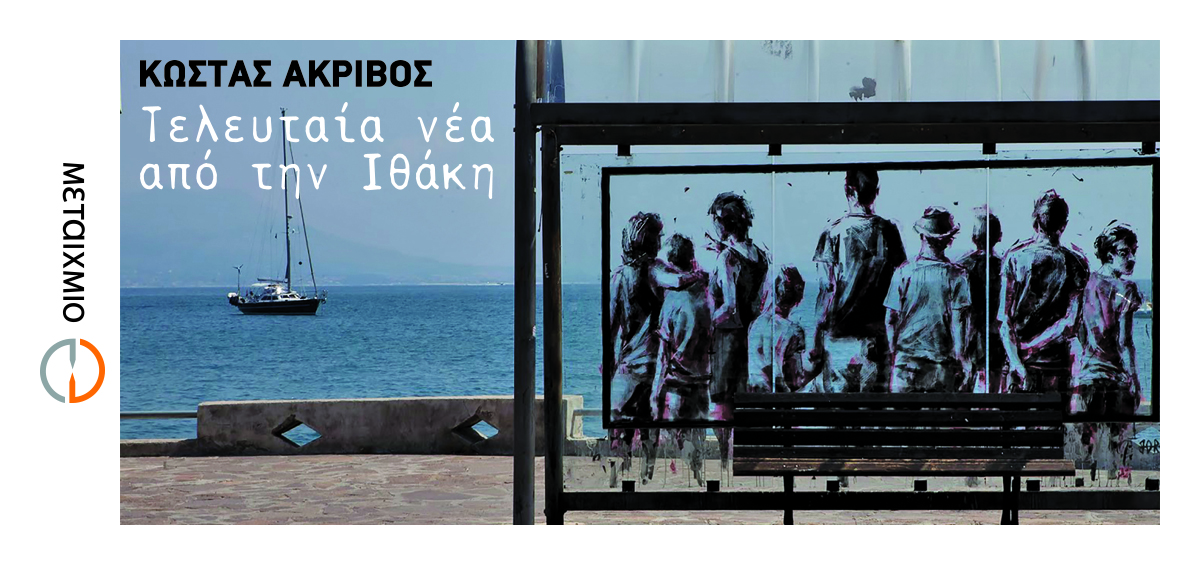

Kostas Akrivos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book Τελευταία νέα από την Ιθάκη [Latest News from Ithaca], noting that it comprises “stories inspired by characters from the Odyssey, which however take place in recent times of Greek history”. He comments that only literature “may bring out and accurately depict behaviors and people whose remains fertilize the never-ending field of great history”, adding that in the book it was necessary to “forge the individual voice of each of the characters” in order to achieve accuracy and plausibility.

Asked about the preference of contemporary Greek writers for short form, he explains that short form allows them to “better and more effectively depict a wide range of personal quests and concerns”. He notes that the literary texts written for a city “constitute the best compass not only to enter a city but to leave a city relatively unscathed” and concludes that much needs to be changed in the Greek educational system so that school becomes attractive and acquires a meaningful role.

Your most recent book Τελευταία νέα από την Ιθάκη has received rave reviews. Tell us a few things about it.

The book comprises 26 stories inspired by characters from the Odyssey, which however take place in recent times of Greek history: Penelope is a newly-wed woman who lost her husband during the German Occupation; Achilles is an army officer who fought in 1922 and deserved to remain immortal; Calypso is the mistress next door; Telemachus is a gypsy boy who yearns for his father; Athena is a mother-protector of her children; Helen is the archetypal beautiful woman always stirring up trouble; Laertes is Kolokotronis mourning for his killed son; Elpinoras is an unfortunate lad from Crete in the Balkan wars; Polyphemus is a ravenous monk; Tiresias is a resourceful fortune teller… And Odysseus is captain of this voyage as well, although an unexpected Odysseus.

In his review of the book, Giorgos Perantonakis comments that you use the myth as a way to approach History in a trans-historical, inter-temporal framework. How is history inscribed in your writings?

I’m interested in history as the framework within which a country’s past is inscribed; yet I am mostly attracted by unwritten history, meaning events and individuals that remain lost in obscurity and anonymity. I am of the opinion that literature – and only literature – may bring out and accurately depict behaviors and people whose remains fertilize the never-ending field of great history.

What about language? How important is language in its multiple variations and dialects for the accurate depiction of both time and space?

I am an inhabitant of a great – in every respect – language. My language is my country. Within it and with it I express myself, communicate, write and dream. By writing a book like this, where polyphony was imperative, it was necessary to listen attentively and then forge the individual voice of each of my characters. I thus decided to crack the homogeneity of narration, allowing the characters instead to express themselves in their own distinctive way so as to achieve both accuracy and plausibility.

It has been noted that in the last few years, Greek writers have turned to short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. Having written in both genres, how would you comment on this trend?

For a novel to be successful, it is crucial that its central theme moves beyond the boundaries of individuality or local collectivity, to embrace a universal idea. As Herman Melville eloquently put it, the theme is everything! If contemporary Greek writers feel an inadequacy in this respect, they quite successfully turn to short form, where they can better and more effectively depict a wide range of personal quests and concerns.

“We need the literary profile of cities in order to be able to delve into their deepest spirit”. Tell us more.

History and Geography may be good and useful, but I believe that the best way of opening up the gates to a city is to feel its scratches, to know its paths and people, both contemporary and long gone, to familiarize with its sins, both explicit and concealed, to impress it in literature. The literary texts written for a city, meaning its literary map, constitute the best compass not only to enter a city but to leave a city relatively unscathed.

What about the Greek educational system? How could literature become attractive to students? What role should teachers play in this respect?

There is lack of progress in many fields in contemporary Greek schools: mistakes that are repeated, indistinct and pointless objectives, ailments that remain uncured. The study of literature unfortunately remains one of the weaknesses of the education system. Much needs to be changed (books, teaching methods, priorities etc) if we really want students not to graduate semi-literate or functionally illiterate. Literature could help this change. The state however must respect literature and books, and all that is related. Only then could there be hope for school to become attractive and acquire a meaningful educational role.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE