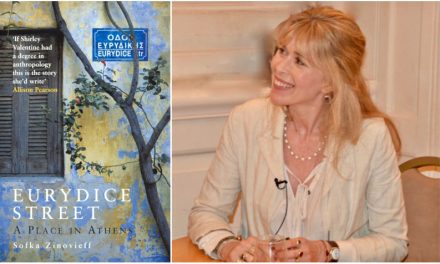

Lena Kallergi (1978) is a poet and translator. She has published two books of poetry: Κήποι στην άμμο (Gardens on sand, Gavrielides, 2010) – which received the Maria Polydouri Award for New Poets – and Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο (One ship apart, Gavrielides, 2016); as well as two volumes of poetry in collaboration with the ‘Ομάδα Από Ποίηση’ (Poetry Team, Gavrielides, 2010 and 2012). She has translated poetry by Giacomo Leopardi, Luis Cernuda, Mario Vitti and others.

Lena Kallergi spoke to Reading Greece* about her two poetry collections noting that while the former was “about stubbornly defending my dreams even if the soil where I could cultivate them was not always ideal”, the latter is “about coming to terms, at least partly, with uncertainty, with the unknown, and with continuing the journey even when a feeling of being adrift is prevalent”. She discusses the dominant role of the sea in her poems, while she comments that her poems, though not surrealistic in their entirety, bear “traces of surrealism” noting that “poetry and reality constitute both complementary and contrasting concepts”.

She concludes that she is “fortunate to be part of a generation of poets that includes so many diverse and talented voices” and that “the act of creating significant art is an act of faith and resistance in itself and it can become a vessel of, among other things, beauty, truth, and hope. Poets will continue to create and to enclose these treasures in their work”.

Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο was recently published, almost six years after your first poetry collection. What differentiates this collection from Κήποι στην Άμμο? How has your poetry evolved over the years?

Six years is a long time, much has happened, I evolved as a person, and my second book feels to me very different from the first one. It is more about moving away from myself and venturing out into the vast, always unknown world. Κήποι στην άμμο was, in many ways, a book about stubbornly defending my dreams even if the soil where I could cultivate them was not always ideal. Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο can be read as a book of autonomous poems about traveling at sea and about a language evolving, but also as the journey of a person, of a language, and of poetry itself.

The sea is dominant in both books but it assumes a different role in the second one, where the human body emerges as one of the very few certainties a person can have during a lifetime. It is also a book about coming to terms, at least partly, with uncertainty, with the unknown, and with continuing the journey even when a feeling of being adrift is prevalent.

The sea, the journey, travelling, change and their transcription to the body and language are recurrent themes in your poetry. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

I grew up near the sea and I carry it with me wherever I go. After I left my hometown in Evia, I lived in Patra, San Diego, Lancaster, Athens, and I travel to other countries and cities. I always need to know where the sea is in order to understand my coordinates, my position on the map. Reading, traveling, moving from place to place and from language to language, working as a linguist and a translator, meeting people and hearing their stories, having access to their writings, being a writer myself, growing older; all these things have defined me, in a way, and I guess they live in my poetry. Other than that, anything can be a reason for a poem.

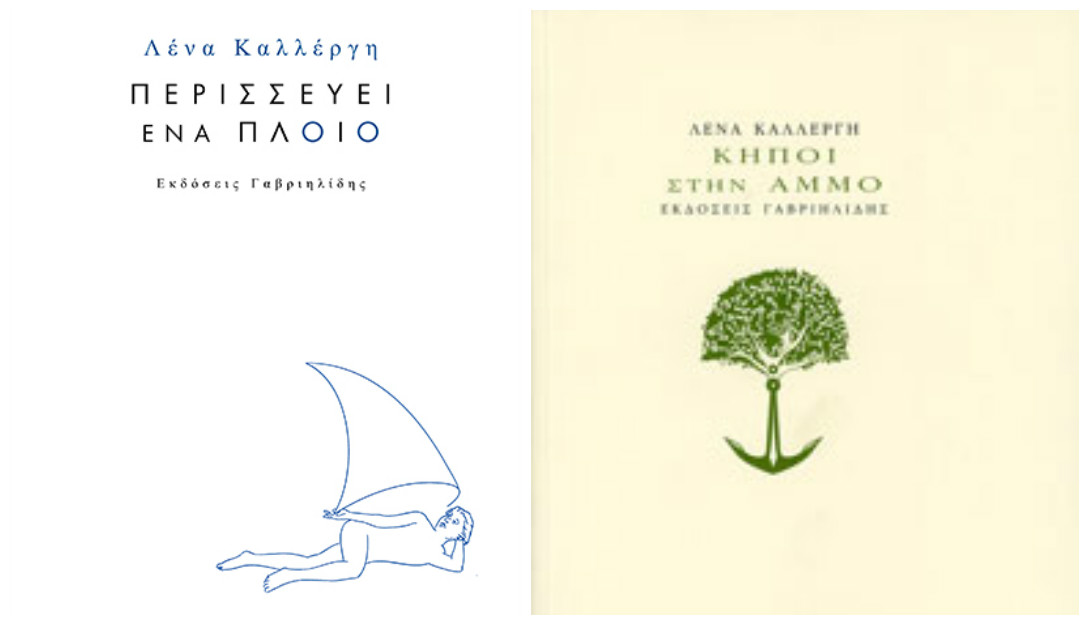

In his review of Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο, Dimitris Athinakis notes that “in most poems, we delve into what the mind perceives as its own reality, which in no way upsets the waters of the reality of others”. Would you characterize your poetry as surrealistic? What has been the influence of Nikos Engonopoulos on your work?

Nikos Engonopoulos is one of my favorite Greek poets. I am never tired of reading his work. His poetry makes me feel free and makes me want to write poetry, so he must have influenced me a lot. I do not consider my poetry to be surrealistic, even though traces of surrealism can be found in it, but then again, traces of surrealism can be found almost everywhere. I think what Dimitris Athinakis observed is that the world my poems suggest in Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο is not a world which wants to impose itself on others. Different realities can exist simultaneously without necessarily being in conflict.

The poetic voice in Περισσεύει ένα πλοίο is a traveler in awe of his/her own ignorance and uncertainty, be it existential, linguistic, or other. So, there is a lot of room for differences, multiple realities, and undecided routes. The ship mentioned in the title and present in almost every page of the book «περισσεύει», it is the odd one out; it is redundant, but also excessive, superabundant as in surplus, and also a unique, special vessel. I chose this title because it allows for multiple meanings and interpretations and it includes both positive and negative connotations concerning the status of the ship.

“In poetry I find ways to understand, to feel, to communicate a deeper layer of experiences, images and desires”. How is poetry related to reality? Do they constitute complementary or contrasting concepts?

I would say that poetry and reality constitute both complementary and contrasting concepts. At times, “contrasting” means “complementary”, and vice versa. Language has many ways of creating categories that both facilitate and confine communication. I do not find that I escape reality by reading or writing poetry, and I do not think I construct a completely separate reality with my poems. Poetry is my window, my tool, my secret music, my third leg and my limp, my facilitator and my biggest challenge, my beautiful rose and ugly truth, my imaginative reality.

You have published two volumes of poetry as a part of the ‘Oμάδα Από Ποίηση (Poetry Team)’. Tell us a few things about these collective works.

The “Poetry Team”, «Ομάδα Από Ποίηση», was the result of experimentation with a group of poets a few years ago. We met in a creative writing workshop and decided to continue our meetings and working with each other’s poems after the workshop was over. This is how the first group was created. For the second book, we took this experimentation one step further and decided to write on roughly the same subject, drawing from common myths and archetypes that interested all of us. In our second book, entitled Υπέρ Ονειρίας, we did not assign each poem to one poet but considered them all to belong to the Team, thus taking the concept of collaboration to a new level. These experimentations were very fertile and helped me discover a lot about my personal identity as a poet, my preferences, etc. Poetry is essentially a lonely art; going against this reality does not change it, and it shouldn’t, but this journey offered me knowledge, encouragement, and friendship.

What about the new generation of Greek poets? Could poetry act as a paradigm of political action in the current unfavorable social conjuncture?

I am fortunate to be a part of a generation of poets that includes so many diverse and talented voices. It is motivating, challenging and enjoyable to read so much good poetry in our times. I often hear and read about the vast amount of bad poetry that is written and published today, but I want to stress the fact that I encounter poetry of great strength and originality very frequently. These remarkable poems constitute political actions, as far as I am concerned, in any social conjuncture, not only in the – especially unfavorable- current one. The act of creating significant art is an act of faith and resistance in itself and it can become a vessel of, among other things, beauty, truth, and hope. Poets will continue to create and to enclose these treasures in their work.

* Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE