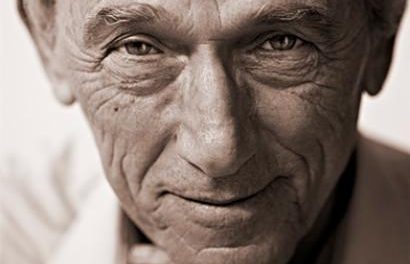

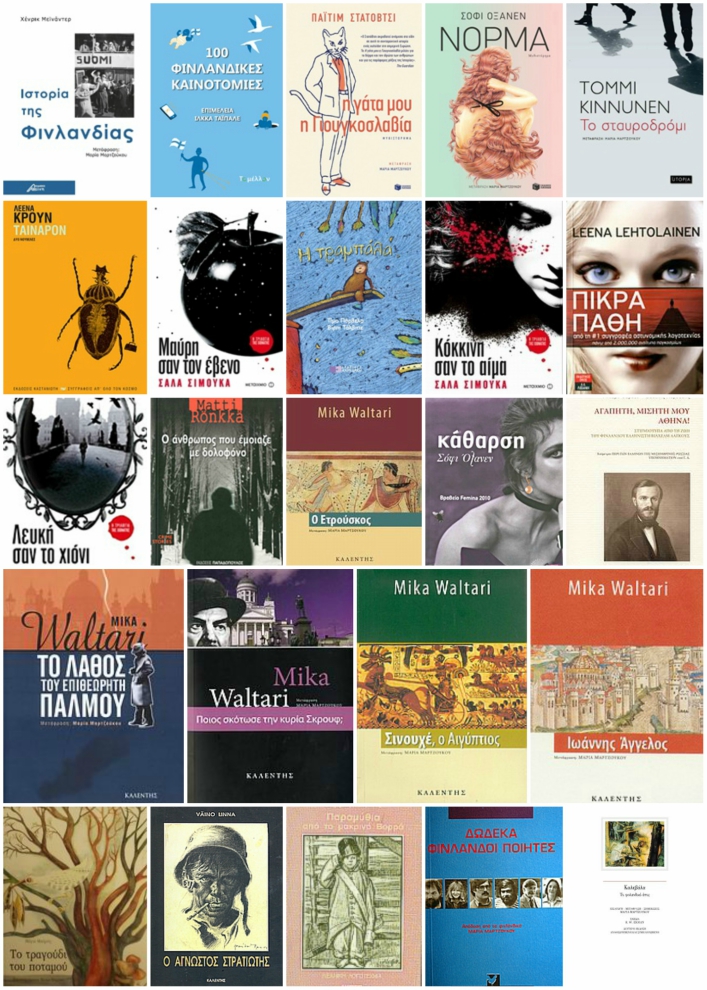

Maria Martzoukou was born in Corfu. She studied Ancient Greek and Finnish Philology at the University of Helsinki as well as Modern Greek Philology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her translations and essays have been published in literary magazines, mainly the Corfiot literary magazine ‘Porfyras’. For her translation of the Finnish epic Kalevala she received an honorary distinction by the Hellenic Society of Translators of Literature (1994).

She also received the ‘Order of the White Rose of Finland’ by the Finnish state for her contribution to the dissemination of Finnish letters (1996). She is a member of the Finnish Literature Society and the Kalevala Society. In 2011 she was awarded with the Finnish State Translation Award for foreign translators. She has been working at the Finnish Institute of Athens since 1985.

Maria Martzoukou spoke to Reading Greece* about what drove her to the Finnish language and the translation of Finnish literature, as well as on the main challenges she was faced with while translating Kalevala, one of the major epic works of Finnish literature, noting that her intention was “to lay emphasis on its poetic dimension so as to bring forward the common myths that unite peoples around the world”.

She also comments on the peculiarities of translating literature from Finnish to Greek, explaining that given that “Finnish is a concise language”, “attention should be paid to avoid unnecessary rambling”. She concludes that “literature constitutes an anatomy into the body of language”, adding that “the question is whether foreign readers actually want to realize that in Greece there aren’t just Zorbas”. “While I was in Finland and I had the chance to teach the Greek language, I tried to make them understand that the Greeks are a people which strives to survive, just as the other peoples, and that the sun and the sea don’t constitute the ultimate good”.

What drove you to the Finnish language and more specifically to the translation of Finnish literature?

Everything happened by chance. While I was studying in Finland, I attended a Finnish language and culture curriculum, which also included literature courses. Trying to make sense of some texts, I translated them in Greek. It never crossed my mind that these translations were of some literary value. At some point, I showed them to a friend of mine, who, in turn, showed them to a member of the editorial board of the literary magazine “Porfyras”, the late poet Dimitris Sourvinos. “Porfyras” played a major role not only in my career as a translator but in my personal life as well.

You have translated Kalevala, one of the major epic works of Finnish literature, in Greek. Which were the main challenges you were faced with?

I have translated part of the epic, that is 20 out of the 50 songs. I am waiting till my retirement to continue! I hope Ι’ll make it in time! Kalevala is based on the oral folklore collected by Elias Lönnrot. It is a poem and should be translated as such. Yet, in which meter? The trochaic tetrameter, as in the original? Or better yet a meter the Greek reader is more familiar with?

My intention was not to deal with the saga as if it were a museum token or an archival material, but to lay emphasis on its poetic dimension so as to bring forward the common myths that unite peoples around the world. That’s why I opted for the iambic fifteen-syllable verse, which we use in our demotic poetry. This working hypothesis is not unique. Several other translators have opted not for the trochaic tetrameter of the original but for their own folklore poetry’s meter in order to translate Kalevala in their language. If translation is not just, as we believe, a bare act of imitation but rather a free and equal conciliation between two languages or texts, then such ‘arbitrary’ choices are perfectly justified.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this context, what are the peculiarities of translating literature from Finnish to Greek?

The translator is called to find out the suitable matches to the particularities of his/her own language. Finnish is a concise language, full of impersonal passives and participles, it has no articles nor prepositions – which are expressed through cases. Attention should thus be paid to avoid unnecessary rambling.

Ιt has been argued that when translating from a so-called “minor” language or literature, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie?

Translators of minor languages constitute the ambassadors of literature and thus they bear enormous responsibility.

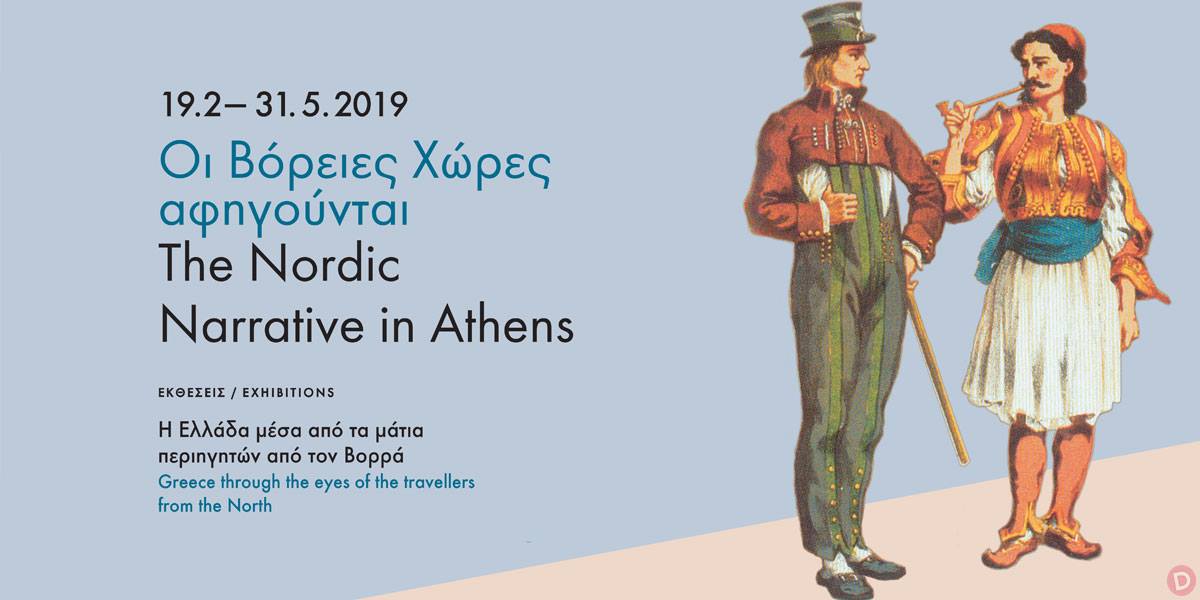

Within the framework of “The Nordic Narrative in Athens”, there took place an exhibition titled “Greece through the eyes of the travelers from the North” (19.2-31.5.2019). Tell us a few things about this initiative.

In 2006 there was published in Finland a book titled Kadonnut Kreikka – suomalaisten matkakuvauksia ennen massaturismia [The lost Greece. Travelling impressions of Finns prior to massive tourism] edited by Björn Forsén και Erkki Sironen. This book was quite enlightening for me so I started to delve into Finnish travellers, who are in fact quite numerous.

In Greece, there preceded the publication of a book in Greek, which we prepared together with Vassilis Letsios, assistant professor at the Ionian Univesity, titled Ένα καράβι αχνοφαίνεται στον ορίζοντα. Ο Φινλανδός περιηγητής Όσκαρ Έμιλ Τουντέερ στην Ελλάδα και το Χισαρλίκ (1881-1882) by Assini Editions. So when it was asked from the Nordic countries to participate in the festivities of “Athens, World Book Capital”, we thought that the theme of travellers perfectly suited the occasion. We also organized an event on the Nordic crime novel, which is very popular in Greece.

There is undoubtedly a stereotyped perception of Greeks abroad. Could literature be used to shake off these stereotypes and help form a new narrative about the country?

Literature constitutes an anatomy into the body of society and, in this respect, provides the opportunity to make sense of the society it describes. Yet, the question is whether foreign readers actually want to realize that in Greece there aren’t just Zorbas? While I was in Finland and I had the chance to teach the Greek language, I tried to make them understand that the Greeks are a people which strives to survive, just as the other peoples, and that the sun and the sea don’t constitute the ultimate good.

* Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE