Michaela Prinzinger was born in 1963 in Vienna, Austria. She studied Byzantine and Modern Greek Philology as well as Turkology in Vienna (1981-86). An academic assistant at the Free University of Berlin from 1990 to 1995, she was also a Post-Doc Fellow at Princeton University (1997-98). Since 1999, she has been a free-lance literary translator (from Greek to German), a project leader and a moderator. In 2005, she became an officially authorized translator and sworn interpreter for the Greek language.

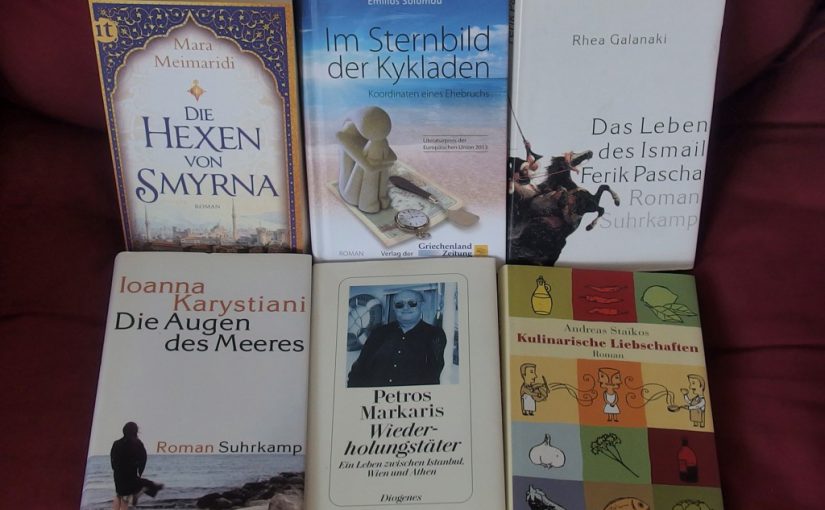

She has translated the works of Petros Markaris, Rhea Galanaki, Ioanna Karystiani, Loula Anagnostaki, and many others. In 1995, she was awarded the Joachim Tiburtius Prize, followed by the Greek-German Translators’ Prize in 2003. In 2014, she created diablog.eu, German-Greek encounters, a bilingual communication and exchange platform that aims to contribute to the proximity of Greek and German people through culture. In 2015, she received the Austrian State Prize for Literary Translation for the entirety of her work.

Michaela Prinzinger spoke to Reading Greece* about diablog.eu, German-Greek encounters, noting that “a true cultural policy should stem from civil society and not from the senior ranks of cultural institutions” and that diablog.eu has somewhat become “an alternative, unofficial Greek-German cultural institution” with a cultural policy that “comes from the base, from the center of civil society, where art and culture actually belong”. She explains that the next project underway is “the promotion of a cultural dialogue between the North and the South” through a nonprofit association in Berlin “which will aim at the development of new ideas and projects that will open up unprecedented and unexpected prospects“.

She comments that the way for Greek literature to be perceived as good literature without the need for folklore arguments is “through the development of tools that will strengthen literary translation” adding that “the Greek-German translation funding program needs an innovative approach which should go beyond unilateral, national support for translation projects”. She concludes that Greek writers are faced with almost insurmountable problems in order to have their voice heard abroad, given that, among others, “a coherent policy for the financing of current cultural transfers abroad, i.e. in the field of literature, is nonexistent”. “Yet, when there is a will, there is a way […] ideas do exist, which of course should be further spread. It’s high time the Greek state does away with its current stance”.

diablog.eu constitutes a bilingual communication and exchange platform that aims to contribute to the proximity of Greek and German people through culture. What’s the story behind it? What are its main fields of focus and its targets?

diablog.eu, German-Greek encounters, is an online project of understanding between nations. Our motto is: culture connects; much more than money or economics. The project has sprung from the – somewhat strained in recent times – relationship between Greece and Germany. This dialogue can serve as a model for future co-operation in Europe. Up to now, diablog.eu has been a voluntary project, working only with the symbolic capital of knowledge, education and culture.

The aim is to establish a network between people, rather than institutions. To build a solid bridge, we need two pillars: the German and the Greek language. The site started as a low-budget project that draws upon the co-operation of interested and engaged people. The next step is to set up a nonprofit company. In this respect, diablog.eu will act as a laboratory of ideas and a networking tool; a starting point for many initiatives.

diablog.eu has been online since August 2014, and we also have a social media presence on Twitter and Facebook, including the Facebook group diabloggers.eu (more than 3000 members, which represent a perfect German-Greek target group). Via our social media profiles, we are reaching up to 10.000 users weekly, while our website has recorded over 250.000 visits although we have deliberately decided against news and political reporting. Our project is broadly political and we are always open to any social issues that the cultural sector is grappling with.

What led me to the creation of the bilingual cultural website diablog.eu, German-Greek encounters, was actually the response I received from German publishers and media every time I proposed a Greek issue: Nobody here is interested. I refused to accept this unconditional conviction. I had friends who had repeatedly asked me to recommend Greek writers, musicians, artists. That’s how I came up with the idea to start a platform, a knowledge base, a source of information, which would promote cultural exchange.

What motivates us is not just the idea of a network, but the involvement of civil society as well. A true cultural policy should stem from civil society and not from the senior ranks of cultural institutions. Meanwhile, we have somewhat become an alternative, unofficial Greek-German cultural institution with a more human touch, while our cultural policy comes from the base, from the center of civil society, where art and culture actually belong. Our approach is at a personal level; we do not constitute an impersonal business project but we are rather active citizens showing solidarity.

The question is: Who is responsible for a country’s culture? The state? Individual maecenas and private sponsors? Or maybe all of us, the citizens right in the center of civil society, who do not want art and culture to be considered distant, elitist phenomena?

Would you say that, in times of crisis, culture constitutes the most effective way of communication and understanding among European countries, and especially between the countries of the South and the countries of the North?

Europe needs the concept of diablog.eu. The idea could be applied to many other North and South regional relationships, where economic decline dominates the discussion. For us, creative economy means a culture of exchange, of give and take, of gift and counter-gift.

We want to open up a channel of dialogue for people who have, up to now, depended upon mainstream media coverage. To this end, we rely on help from bridge-building translators. Our common wealth is the culture we can all share. This potential could be perfectly fulfilled through the internet. Diablog.eu is not about our differences but about our similarities. Its aim is to finally cast off this outmoded philhellenism, an idealization of the Greek heritage cultivated up to the 70s and to define anew the image of Greece through a more political perspective, i.e. stemming from resistance to the Junta (1967-1974).

It is about the work of contemporary Greek authors, visual artists and musicians, who live in Greece or who, due to personal networks, work in German-speaking areas. It is also about creative people who work in German-speaking areas and share an intellectual or personal relationship with Greece that is imprinted upon their work. It is important to show that this wealth of intellectual exchange actually exists, both to raise awareness and for pleasure.

We are already preparing the next step, namely the promotion of a cultural dialogue between the North and the South. As we speak, a nonprofit association is underway in Berlin, which will aim at the development of new ideas and projects that will open up unprecedented and unexpected prospects. Based on diablog.eu‘s concerted effort of the last two and a half years to cultivate a cultural dialogue on equal terms, this organisation in Berlin will be in position to offer some worthy and viable work through its effective networking.

On the occasion of your being awarded the Austrian State Prize for Literary Translation, you said that the Modern Greek culture is not easily understandable in a German-speaking audience. What is it that German publishers ask from Greek literature? What makes Petros Markaris so popular among German readers?

The novel is of course the literary genre publishers are more interested in (and obviously the same goes for readers). The interest for short stories is significantly lower, while poetry lovers constitute a small, yet fervent sect. The most renowned and popular modern Greek writer is without doubt Petros Markaris. One of the reasons is because his German-speaking publisher is quite caring and promotes him in the appropriate way. Markaris also speaks German so he is regarded by the German media as a coveted correspondent and interpreter of Greek issues.

Through his humorous and at the same time detached – due to his cosmopolitan background – look as well as through the vividness of the characters he describes, Petros Markaris has managed to transfer his German-speaking readers to the everyday life of Athens. He refers to familiar, global issues that his readers both in the Greek and the German-speaking world can identify with.

Would you agree that when translating from a so-called “minor” to a so-called “major” language or literature, translators – as “cultural politicians” to use your own apt characterization – do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power?

Every translation has its own expiration date, which has to do with the evolution of language as a living and constantly changing system. Every translator has his/her own responsibility. In literature, mistakes are much less important compared to those made within a political or legal framework. A misunderstanding in a literary text doesn’t usually cost human lives, although it is rebuked by some literary critics and readers as a crime. Let’s not exaggerate. Languages are open symbol-bearing systems, which allow for different interpretations. A word may hold both great power and weakness, as you mention in your question. Through subtle linguistic variations, I can approach the reader or alienate him from a text – and the same goes for a way of thinking or a mentality.

“What actually continues to restrict Greek literature, despite efforts to become known in Europe and the world, is the legacy of the “Zorbas syndrome”; that folkloristic image continues to exert influence”. Do you see a way out?

The real question is: How can modern Greek literature be perceived as good literature, without the need for teasers, such as pictures, motifs and folklore arguments? The answer is only through the development of tools that will strengthen literary translation. When it comes to historic research and the field of academics, such measures can actually have desirable results. This is obvious, for instance, in the cases of Deutsch-Griechischer Zukunftsfonds [Greek German Fund of the Future] and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. There isn’t anything similar in literature.

The Greek-German translation funding program needs an innovative approach which should go beyond unilateral, national support for translation projects. In this way, there would be created an interesting approach for other “language pairs”, so that the Greek-German example could act as a pioneer in the European cultural mediation. Literary cultural exchange would thus be improved, would exceed national borders and would be implemented at a European level in the fields of language, culture and mentality.

Our proposal is: The idea starts from two linguistic and cultural areas – a German-speaking, comprising Germany, Austria and German-speaking Austria, and a Greek-speaking one, including Greece, Cyprus and the Greek Diaspora. It refers to a dialogue between these cultural areas, a dialogue which has so far been unilaterally funded, that is by each respective nation. It’s about moving beyond this approach and creating a transnational Fund that will be financed by national, regional and inter-regional funds, private organizations and institutions, as well as by EU funding.

What about the potential and prospects of the new generation of Greek writers? Would it be possible for them to debunk stereotypes and create a new narrative about Greece?

In one way or another, good literature debunks stereotypes. That’s not the issue. What worries me more is that both younger and older writers are faced with two major, almost insurmountable, problems:

a) In German-speaking publishing houses, there is almost no permanent personnel, that is editors, that know Greek. This reduces the chances of a book being evaluated right from the start. The editor should speak out and support a book in order to convince the publisher and his colleagues of its quality. That’s something quite difficult when the editor doesn’t know the language. Given that there is no tradition for translations of modern Greek, each editor (as well as each translator) has to start the evaluation and mediation virtually from scratch.

b) From my personal experience in Greece, there is no coherent cultural policy in general, let alone a cultural policy addressed to the outside. What is true for every other Greek state policy also applies to the cultural state policy: Major projects are implemented by active individuals and the intervention of the state leads to projects being impeded. In addition, GREAT strength and patience are required by Greeks themselves, who have to wait for months, if not years, to receive their earnings or potential funding.

Let me give you some concrete examples from the field of books and literary translation, which I know well of: The National Book Center of Greece (EKEBI) and the European Translation Center (EKEMEL) were among the first victims of austerity. Hellenic Foundations for Culture abroad, among which that of Berlin, ceased operations or are under-operating. A coherent policy for the financing of current cultural transfers abroad, i.e. in the field of literature, is nonexistent.

Yet, when there is a will, there is a way. And as I have already mentioned, ideas do exist, which of course should be further spread. It’s high time the Greek state does away with its current stance.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE