Environmentalist, geographer, and engineer, Michalis Modinos was born in Athens in 1950. He has lived and worked in several countries on behalf of international agencies and organisations. He has published the following novels: Golden Coast (Kastaniotis, 2005), The Great Abbai (Kastaniotis, 2007), Homecoming (2009), The Raft (Kastaniotis, 2011), Wild West: a love story (Kastaniotis, 2013), Last Exit: Stymfalia (Estia, 2014) and Equatoria (Kastaniotis, 2016). He has won several literary prizes and distinctions, among them the European Prize for Literature. His scientific works include: Myths of Development in the Tropics (1986), From Eden to Purgatory (1988), Topographies (1990), Where is the World Heading to? (1992), The Development Game (1993), The Archaeology of Development: Green Perspectives (1996), The Eco-geography of the Mediterranean (2001), The Pathways of Sustainable Development (2003), Globalization and the Environment (2004).

He has been an environmental activist, the editor of the monthly review New Ecology, and the author of numerous publications on environmental and development issues. He was President of the Greek Agency for the Environment and Sustainable Development, and the director of the Greek edition of The State of the Planet, in collaboration with the WorldWatch Institute. He has taught in academic institutions, and from 1998 to 2010 he ran the “Summer Ecological University”. He is a member of the administrative board of the Hellenic Authors’ Society. Since 2005 he has regularly been writing book and literary reviews for the daily press and several publications.

Michalis Modinos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest book Equatoria, which is “a three level story about the years of the colonization of Africa, recording the story of the 19th century search for the sources of the Nile”. He notes that “Black Africa rarely appears in Greek novels” with the exception of “Alexandria with its extended Greek community that has attracted Greek writers” and explains that the western literary tradition usually depicts Africa “as a savage, mysterious place, full of magic and secrets to decipher”, “the unknown strange framework where adventures take place and where the origins of humankind are traced”.

Asked about how history, politics and fiction are intertwined in his books, he comments that “the conflict between progress and tradition or modernization and underdevelopment” is often discussed in his writings, noting that his books belong “to the tradition of the perpetual conflict of civilization and nature”. He concludes that “great narratives have been discredited nowadays and a good novel helps reconstruct reality (the World) and place ourselves in it”, while “it also leads to personal ‘katharsis’ in the Aristotelian sense of the word”.

Almost a decade after The Great Abbai, your latest book Equatoria brings us back to the African continent. Tell us a few things about the book.

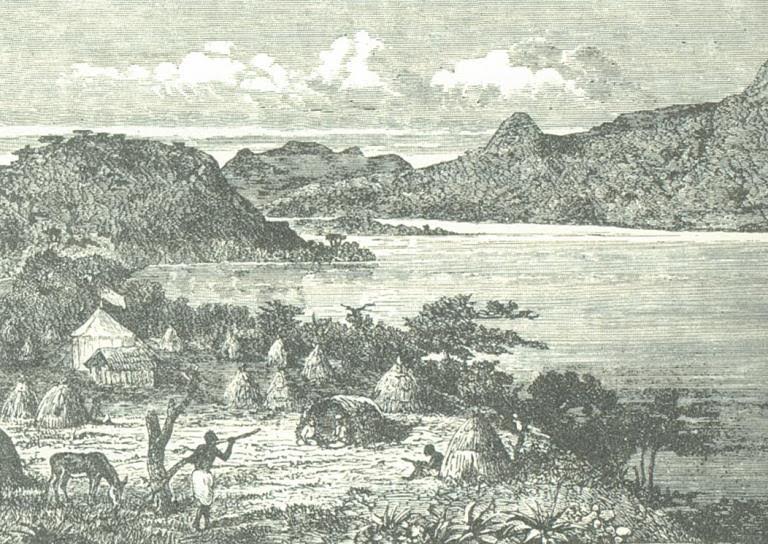

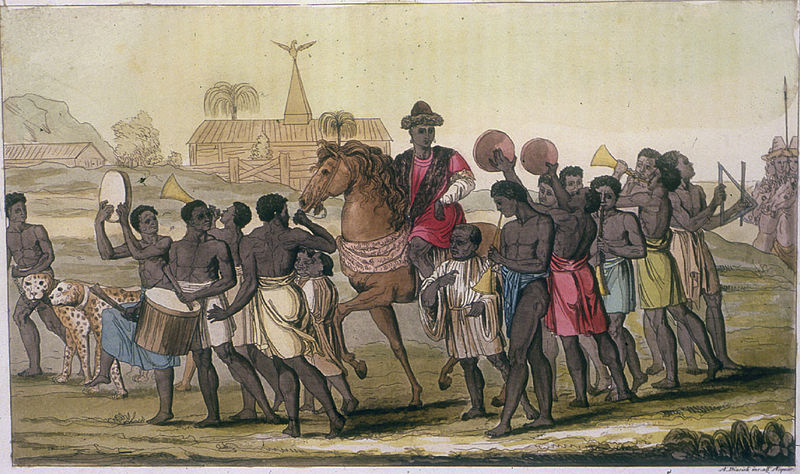

In Equatoria I wanted to narrate a three level story about the years of the colonization of Africa, recording the story of the 19th century search for the sources of the Nile in a genre similar to New Journalism. The language combines journalistic research with the techniques of fiction writing in the reporting of stories about real life events. The plot develops a century after the story narrated in my book The Great Abbai. At the same time I wanted to give a travelogue, a retrospective on the past of the impressions and experiences of a fictional Greek explorer, a wealthy cotton merchant who, setting off from Zanzibar, reaches Equatoria and the Mountains of the Moon.

In fact I gave my name to the central character and narrator of the story in a refection game, taking partial responsibility for his views and reflections. On another level, it was very important for me to discuss, on the basis of real life events, the concept of the construction of a utopia – a hybridic, multicultural society- as it was attempted on the ground in the heart of Africa, the great lakes area of Northern Uganda and Sourhern Soudan (to be deconstructed in the end against the will of the people who created it).

Africa, in its million faces, has been occasionally depicted in Greek literature. What is it that makes Africa appealing to Greek writers? And, in turn, how do you explain the different ways Africa is portrayed in these works? Are there parallels to be drawn with the respective European literary tradition?

Black Africa rarely appears in Greek novels as a matter of fact. It is usually Alexandria with its extended Greek community that has attracted Greek writers (Tsirkas, Kavafis etc). The western literary tradition, in which Greek writers are certainly included despite the language gap, often used Africa as an appealing background, mostly in novels. Writers like Vern or Conrad (to name just a couple) usually depict Africa as a savage, mysterious place, full of magic and secrets to decipher. Elsewhere writers describe African nature and landscape in rather lyrical terms. Africa is the unknown strange framework where adventures take place and where the origins of humankind are traced.

Any of these approaches help the plot to develop as an exotic environment, triggering the imagination of the reader. On the other hand, they shape and sometimes determine the central characters of a book. Some modern writers, including myself, use the African landscape or setting in general as characters equally important to human ones.

A researcher, environmental activist, geographer, traveler, fiction writer, literary critic. Where do all these attributes meet? Does writing constitute the binding thread?

Without a doubt. Since I was the founding editor of the influential monthly review New Ecology, and managed it for fifteen years, I tried, along with a group of intellectuals and activists, to popularize scientific questions and to build bridges with political action at both local and international level. This is how my first essaylike research books were initiated, starting with Ecogeography: Myths of development in the tropics (already in its sixth edition, something rather out of the ordinary for a non literary book). Thus arose the term «Ecogeography» that I also use in literary terms nowadays.

As regards the binding thread of all those professional occupations that you mentioned, I suppose literature was just waiting for me “around the corner”. If anyone reads my early essays and nonfiction books he will probably understand that despite the scientific and political questions raised, there has always been a narrative tone inherent, inspired by writings of social anthropologists and geographers. Thus, transition to novel writing was not very difficult in terms of style and form. It was rather a question of allowing my imagination to take the upper hand. Now I am completely devoted to fiction literature. I work full time and I find writing somehow redemptive after all those decades of working in academic institutions, international organizations, social movements etc.

Some of your books have multiple references to the cultural and environmental decay of modern societies. How are history, politics and fiction intertwined in your books? And to what end?

I often discuss the conflict between progress and tradition or modernization and underdevelopment: see for example Golden Coast, Homecoming, Wild West – a love story etc. The prevalence of the development idea is mainly a postwar phenomenon – it was then that development became a central goal for practically all societies around the globe. Still my books do not belong to the post-colonial tradition, but rather to the tradition of the perpetual conflict of civilization and nature. I am interested in the circular time of Ecology, somehow more than the linear narration of history anyway. My concern is to incorporate global thematic lines into the destiny of my heroes.

“Literature can by its own means depict reality in turmoil, offering at the same time a way out”. What role does/should literature serve in times of crisis? Should literature and art in general be politically militant?

Maybe now more than ever we must insist on the achievements of Western civilization, where we belong. Of course, my country cannot itself decide where it belongs and that is the tragedy of the times. In any case, to me, the persistence on values like freedom, rule of law, human rights and expanded democracy are nowadays an obligation for writers and public figures in general. It is one thing to adopt tolerance and respect of the Other (which I consistently do in my books) and another thing to accept a mess or even worse than that, imported totalitarianisms. All these topics, in fact, are discussed in Equatoria, together with the cultural conflicts, migrations, early globalization trends and the propensity of humanity to escape the “Beaudlerian ennui”, through immigration and travelling.

What about future prospects? What purpose does depicting a fulfilled utopia, as the one your hero discovered in Equatoria, serve under current dystopic conditions?

Reconsidering the environment and reshaping our lifestyles and traditions, which are gradually being lost, will help us understand the problems and find solutions in times of increasing confusion and acceleration of changes. We need to set goals for the future, and in order to do so, we have to rediscover who we are and what we want to achieve. Still, literature plays a critical role in times of disillusionment. Great narratives have been discredited nowadays and a good novel helps reconstruct reality (the World) and place ourselves in it. It also leads to personal “catharsis” in the Aristotelian sense of the word. One last thing: I believe in cosmopolitanism in literature, a style of researching and writing that deals with the greatissues common to humankind.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE