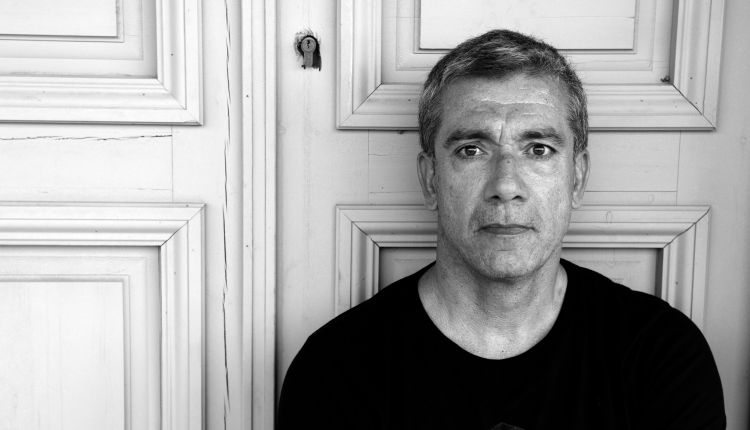

Minos Efstathiadis is an author and playwright. He studied Law in Athens and in Hannover. His play The Meal received the prize for Original Play, was shortlisted for the Eurodram international contest in Germany and has been translated into English, German, French and Hungarian. His novel The second part of the night has been published in German. His latest novel The Diver was shortlisted for the Athens Prize for Literature and has been published in French. He lives next to the sea.

Minos Efstathiadis spoke to Reading Greece* about The Diver, which “talks about the human trauma and its multiplication through time, as well as about the inescapable sacrifice”, explaining that “when the voices of the defeated are heard, the lines between the Good and the Bad become blurred”. He also comments on crime fiction, noting that “we are by far the best murderers” and that “crime fiction doesn’t try to beautify the problem” given that crime fiction writers have “looked at the mirror and sent their responses from the front”. He concludes that although “there are numerous writers who dream of their novels becoming movies and series […] if this is the primary goal, then what is lost is the great adventure of writing and reading: that meeting with the Unknown”.

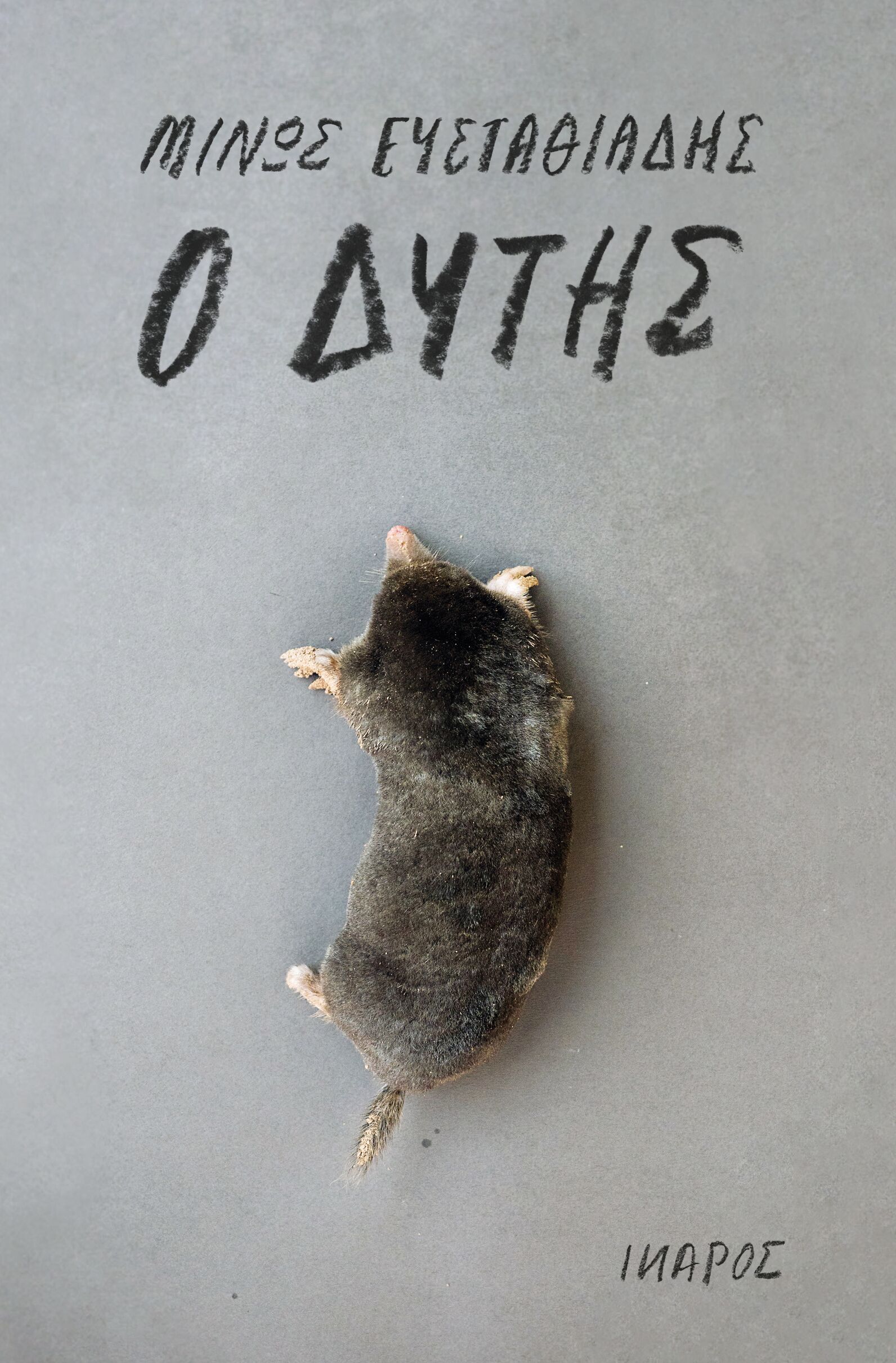

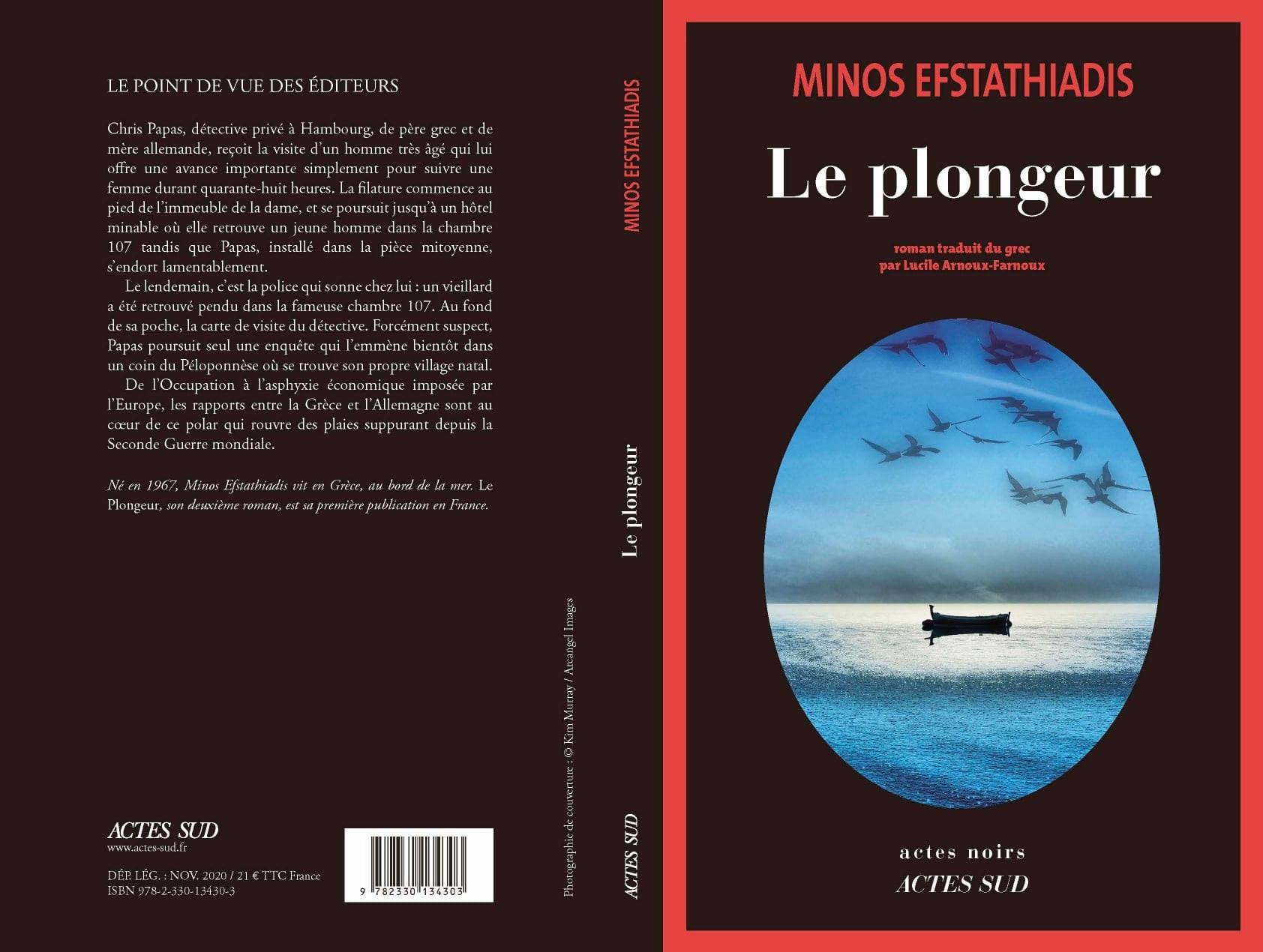

Your latest novel The Diver (O Δύτης) has just been translated in French and has received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

“We couldn’t sleep because of their screams”. Everything was triggered by this relatively simple phrase of my father. He was a teenage boy during the Second World War and Germans had commandeered a building in his neighborhood. He mentioned the story of that ‘house’, for the first time, almost forty years later. Quite often, terror has a crystal clarity that penetrates time. It was difficult for him to find the right words, yet he could still hear the screams of all those who were forced to visit this house.

Official History saves certain parts of the past, yet it (necessarily?) leaves several smaller fragments outside. Fortunately fiction allows for the recording of what was rejected. In a way, it constitutes a means to delay oblivion. Thus I myself tried to remember. To find those lost words.

Ιn his review of the book, Yiorgos Perantonakis commented that the book, although noir fiction on the surface, is more like a tragedy in the ancient Greek meaning of the world, with language enabling a second, deeper meaning of the world. Which are the main themes the book delves into? What about language?

Apart and beyond the various movements of realism, symbolism, romanticism, modernism etc, which have appeared and at times dominated in novels and literature in general, there is, in my opinion, a hard core. Ancient tragedies constitute the first – and probably the most complete – map through this unknown country. Borrowing the emblematic title of Joseph Conrad: In those tales beats the heart of darkness.

The Diver talks about the human trauma and its multiplication through time, as well as about the inescapable sacrifice. When the voices of the defeated are heard, the lines between the Good and the Bad become blurred. Yet, isn’t that what happens in reality?

One of the most difficult bets is the harmonization of the writing style with the narration itself. Each story requires its own language, considering that it’s only through this language that it can take place. And to remain alive, even for short.

The book doesn’t follow a linear narration but rather moves around parallel narrative threads crossing places and times. What purpose does this play with place and time serve in your plot?

Most of the times linear narrations become tiring – at least for me. Maybe straight lines are nothing more that adorned lies. To which end? They create the illusion of a non-existent order amid chaos. Yet, life, thought and memory all move in so many different and lawless ways one could not even conceive. How many times have our intentions, actions or even our whole course changed because something was forgotten? How many times have we felt that we return to the starting point, as if living the same day over and over again?

The past always intrudes in the present. If only we could leave all that has happened behind us, as it is often said. But it’s impossible. We are our past as it moves towards our future.

“Detective novels refer to one of the most interesting habits of the human species: crime”. What made you choose crime fiction as your preferable writing genre?

There are many animals that can kill, yet none of them can compete with man. Only humans have the ability to commit a flawlessly organized crime. We are by far the best murderers. Blood continues to exert an irresistible attraction on us despite the thousands of years of recorded history. Where does this love for its stories come from? From Aeschylus? Even before him? All mythologies of the world are inundated with blood.

To deny a crime is as if we deny a part of ourselves. Are we capable of such an transcendence? Even nowadays, arms trade, drug dealing and human trafficking constitute the three major sources of wealth on the planet.

Crime fiction doesn’t try to beautify the problem. Simenon, Chandler, Highsmith, Larsson, Izzo and so many others did exactly this: they looked at the mirror and sent their responses from the front.

In the last few years, there has been a revival of crime fiction writing in Greece. How is this trend to be explained?

I believe it’s not just in Greece. There is a revival worldwide and there are certainly many reasons behind it. The ‘basic package’ of crime fiction comprises violent death, endless chase, justice served, and often even a love affair.

Let’s consider the everyday life of a man (or a woman) living in a big city nowadays. He lives in a small apartment, wakes up at six in the morning, moves into the flow of the subway or a screen, in order to come back to the surface at six in the evening. He runs back to his few square meters, his island. What does he eat? How does he fall in love? What does he dream of? Which is his most valuable belonging? His cell phone? How does he enjoy his senses? His touch, smell, sound and taste? A murder – even if it takes place through a screen or the pages of a book – automatically arouses his interest. Maybe deep inside it reminds him that, at least, he is alive.

The previous example may constitute a simplification, yet the problem remains. The more we move away from our natural environment, the more alienated we feel. We are extremely thirsty and we need to experience anew the adrenaline of the chase and the joy of survival.

Nordic noir has become a kind of ‘trademark’ in crime fiction worldwide. Would you agree with those who argue that there is a growing Balkan or Mediterranean trend as well?

We certainly owe a lot to Nordic noir considering that it turned the lights to the semi-darkness. For most residents in the West, the surprise was big. There suddenly appeared another world, far from idealized and extremely violent, behind the display of Northern affluence and order. Ibsen and Strindberg spoke loudly about these things a century ago, but Nordic noir had a completely different appeal to the wide audience.

The Mediterranean noir focuses more on social structure and thus on politics. Of course, as is always the case, the most interesting samples come from those who violate the limits between the various genres and give birth to bastard children. The renewal of the genre. Let me mention the case of WajdiMouawad. His novel Anima constitutes his own hybrid, an amazing cross-bread of crime fiction and thriller, a road trip novel with successive monologues and intense theatrical elements.

Since your books have managed to move beyond national borders, what would you say is the ‘recipe’ for a Greek novel to attract foreign readership? How challenging is for Greek literature to reach foreign audiences?

Οne of the most compelling rules of this game is that there are no rules. Moving a step further, I would say that literature constitutes the place where all recipes are annulled.

Lately, there are numerous writers who dream of their novels becoming movies and series on subscription channels. It’s a good idea, which, once fulfilled, may bring new readers, money etc. Yet, if this is the primary goal, then what is lost is the great adventure of writing and reading: that meeting with the Unknown.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Victoria T

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE