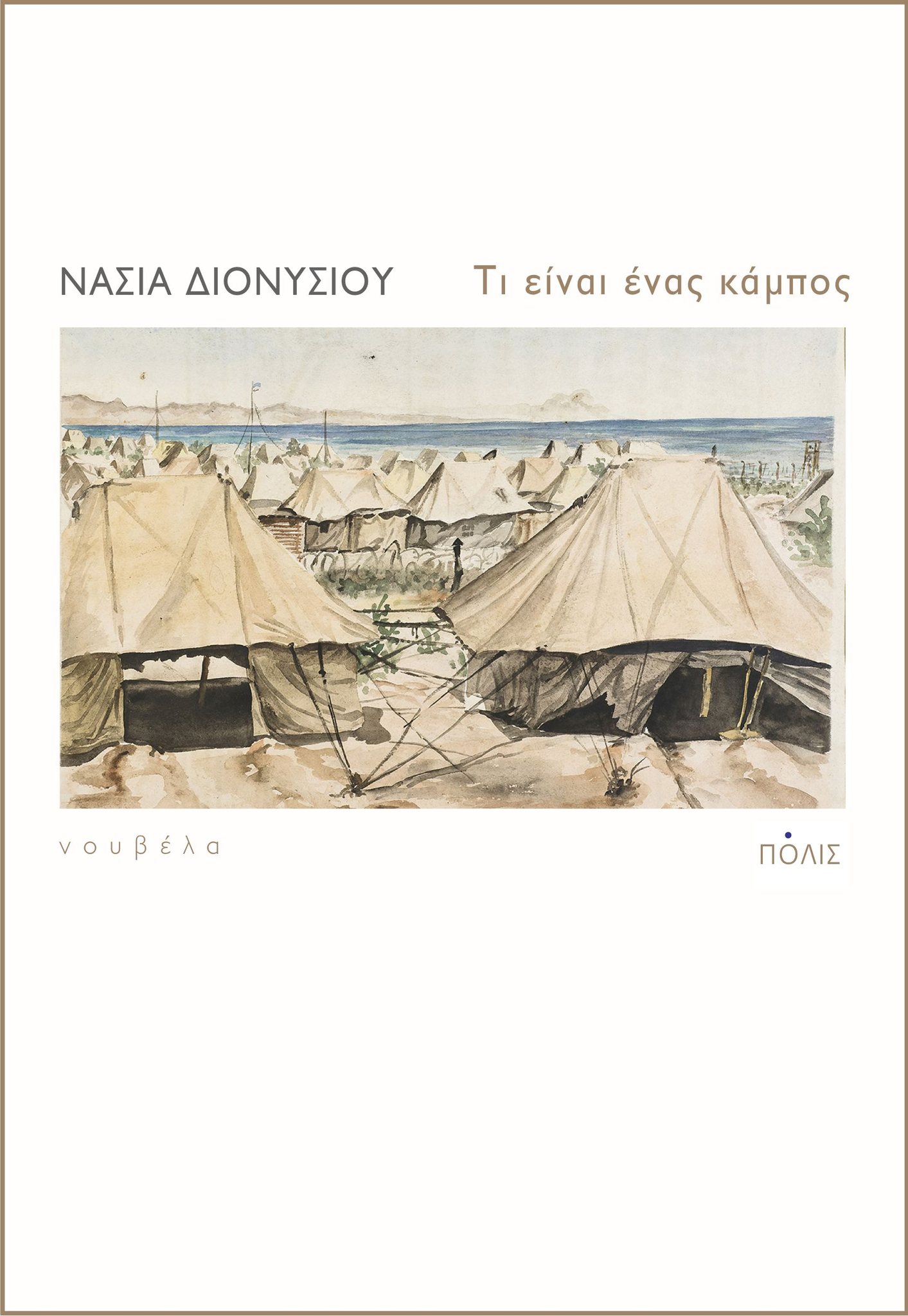

Nasia Dionysiou was born in 1979 in Cyprus where she lives. She has studied Law and International Law of Human Rights and she has been working for the Office of the Commissioner for Administration and the Protection of Human Rights since 2003. Her first book, titled Περιττή Ομορφιά [Redundant Beauty] was published by Rodakio (Το Ροδακιό), Athens, in 2017. The book was awarded the Cyprus State Prize for Short Story/Novella for 2017. It was also shortlisted for the “Anagnostis” 2018 Awards (Greece) in the “Newcomer in Prose” category, translated into Serbian (Treći Trg, Belgrade, 2021) and presented at the European First Novel Festival of Budapest (2019) and the Belgrade Festival of Poetry and Books (2021). Τι είναι ένας κάμπος [What is a camp] is her second book, published by Polis (ΕκδόσειςΠόλις), Athens, in 2021. It was shortlisted for the Cyprus State Prize for Short Story/Novella, the “Anagnostis” 2022 Awards in the “Novella” category and the “Klepsydra” 2022 Prose Award.

Your second writing venture What is a camp constitutes a literary account of the conditions under which the Famagusta camps operated, where, after the end of the Second World War, Jewish refugees were detained on their way to Palestine. Tell us a few things about the book.

Between August 1946 and May 1948, the British government intercepted more than 50,000 Holocaust survivors seeking to resettle in Palestine and interned them in detention camps, that were established on the British-controlled Cyprus. My book reveals and recreates the story of the Cyprus detention camps, through the diary notes of a Cypriot journalist, who, in April 1947, gets a permission to enter the Caraolos Camp, located at the outskirts of Famagusta. By recording the testimonies of the detainees, the journalist presents their current situation and their expectations for the future, against a backdrop of the greatest evil that humanity has ever known. The eerie dreams that disturb the journalist’s nights piece together Paul Celan’s “Death Fugue” (“Todesfuge”) – one of the most world-famous poems addressing the horrors of the Holocaust, while Celan himself is witnessed by the journalist as a shadowy figure who wanders around the camp. The journalist’s narration is interrupted and enriched by three parallel stories, that take place at the same area and period, but outside the camp.

The Holocaust, the relation between memory and history, migration and the refugees are among the main issues the book delves into. How does the past relate to the present in your writings?

Even though there have been several books written about the Holocaust since now, I believe that every new book responds to our anguish to never forget what the Holocaust meant both for the Jews of Europe and the entire European society, as well as to our need to understand what human powers led to such an extreme evil. Unfortunately, this anguish is still relevant, since intolerance, racism and anti-Semitism continue to exist and while multitudes of desperate people continue to cross our seas and borders, finding us hostile and unable to feel that “it only takes a turn of fate to find ourselves in the others’ place”. So yes, although my book starts from a forgotten story of the past, it converses with the present and challenges our personal resistance to blindness and hatred.

“I believe that literature has a living bond with history, since it reminds us of how many personal stories the great history of the world is made of and makes us feel that our own individual journey can also be included and make sense within this great story”. How does literature converse with history?

Literature takes humans from the backstage of History and brings them to its spotlight, revealing not only the reflections of historical events on those who experience them, but also our reaction to these events, and therefore our personal responsibility. In other words, literature isolates the human story that takes place within the wider History, thus making humans tangible, visible and irreplaceable. In this way, through the tremendous tension of fiction, readers reconnect with the reality, realizing not only that History concerns them personally, but also that they themselves may have an impact on History. By extension, literature teaches us not to live blindly, but consciously.And though at no time did the powers of human sensibility prevent the triumph of barbarism, we should do all we can to sharpen our comprehension and our compassion. After all, as Camus has said, “the world’s reality is our common homeland”.

A lot of research was involved prior to writing the book. Which were the main challenges you were faced with?

Indeed, I had to collect information in relation to the circumstances in which the camps were created and operated, something that was not very easy, given that that these events are not widely known and have not been extensively recorded in Cypriot historical sources. Furthermore, I studied a lot about the Holocaust, putting special emphasis on the history of the Greek Jews, mainly the Sephardic community of Thessaloniki and the Romaniote Jews of Ioannina. What I found most difficult, in an emotional sense, was to reconstruct the true stories of the people who experienced the horrors of the Nazi camps and turn them into fiction and narration.

“I prefer the short form, because I am attracted by the density and precision imposed on small texts, the struggle to choose that word or phrase with which as many meanings as possible can be expressed, the penetration in fleeting moments or thoughts that reveal the intensity of a latent consciousness or the significance of a deeper truth”. What role does language play in your writings?

What else does literature mean, if not a struggle with the words and the writer’s effort to free them from the banality of their everyday use and thus give them back their first sense or a new meaning? For me, literary language is not just a useful means to convey information, but what it reduces the distance between fiction and reality and makes the narrative throbbing and breathing. Language, at the same time, constitutes a self-existed, aesthetic value.

How are your literary writings related to your work at the Office of the Commissioner for Administration and the Protection of Human Rights (Ombudsman)? Would you say that they constitute communicating vessels?

The values that led me to study law and to specialize in the field of human rights protection are largely the same ones that motivate my thoughts and writing. At the same time, the real stories,with which I interact every day, permeate my texts, in either conscious or imperceptible ways. They also help me not forget what we defend when we defend human dignity and why this fight always matters.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE