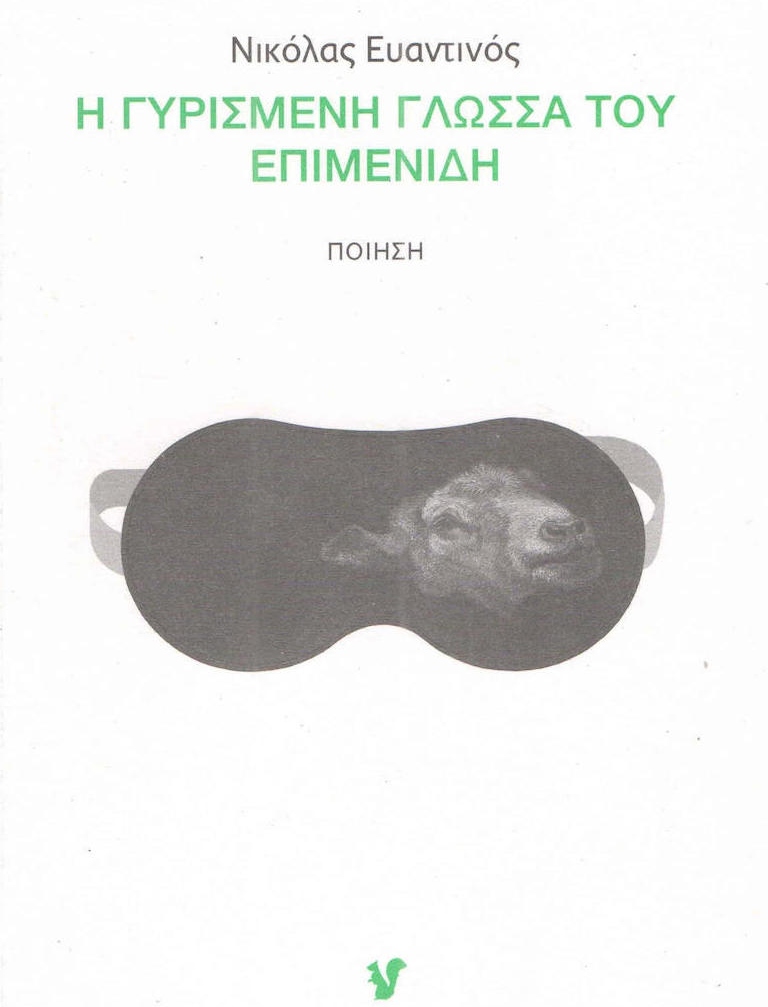

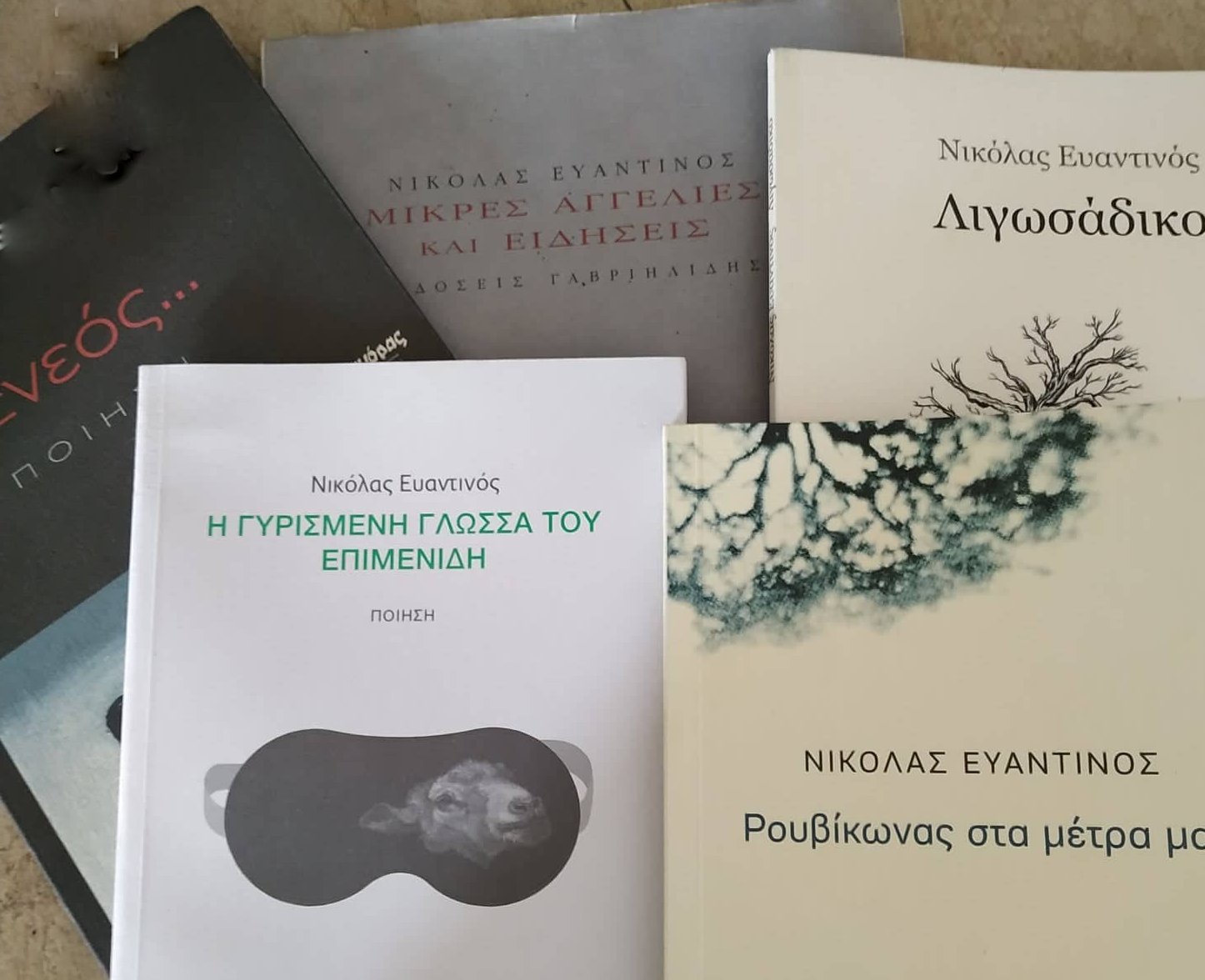

Nikolas Evantinos was born in Ierapetra, Crete, 1982. He studied History and Archeology and pursed post-graduate studies on Modern Greek Literature at the University of Crete. He has published five books of poetry. His first book Μικρές Αγγελίες και Ειδήσεις [Ads and news] (Gavriilidis Editions) came out in 2008, while his latest poetry collection Η γυρισμένη γλώσσα του Επιμενίδη [Epimenides’s curled tongue] was published by Mauve Skiouros in 2019. His poems have been included in various anthologies and have been translated in English and French. He also composes music, writes lyrics and sings his songs with his band.

Nikolas Evantinos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest poetry collection, which uses the myth of Epimenides in order to build upon “the paradox and mystery of the existence of modern man […] in a present fragmented, discontinuous, dramatically elusive and often unbearable”. He notes that “the Cretan vernacular plays an important role in the book as it constitutes its architectural element”, and adds that a binding thread in his poetic presence so far is his attempt to “depict and convey a true feeling of the disability permeating our existence”. He concludes that “poetry constitutes the deepest music of language [while] music is an art with its own high and fundamental value for humans”.

In your latest poetry collection Η γυρισμένη γλώσσα του Επιμενίδη the ancient myth of Epimenides unfolds in the present in an attempt maybe to talk about the existential journey of modern man. Tell us a few things about the book.

Indeed, the myth of Epimenides became an unexpected source of inspiration in order to build my latest book upon the paradox and mystery of the existence of modern man. The sleep of the enigmatic mystic, philosopher and lawmaker in the Idaion Andron, through which conventional time was erased and divine wisdom was born acted as the director’s finding in my attempt to discover that persona who could talk about the present. A present fragmented, discontinuous, dramatically elusive and often unbearable. In an era like ours, hostile towards metaphysical and deep philosophic reflection, a figure like Epimenides could disclose a lot and thus be vehemently castigated. His paradox logic reveals exactly the gap between the poetic Subject and the World. It about the relation between a “nutter” and the ironbound logic of the majority – which as it usually happens – exerts its power over the rest.

Iordanis Koumasidis has pointed to the different linguistic modalities that appear in your poetry. What purpose does this experimentation with language play in your writings?

Maybe the fact that I live in an island with a rich linguistic wealth has contributed to this experimentation. Especially in my last book, the Cretan vernacular plays an important role as it constitutes the architectural element of the book. Generally speaking, I totally agree with Kant who argues that art is purposive without purpose. These experimentations have more to do with play in its deepest Platonic meaning as a means and process towards self-awareness and knowledge. I feel that language, as a poet’s only tangible tool, should be treated as a play that reflects the most sincere aspects of his existence: his moral and aesthetic identity as it is formed and transformed by time.

After five poetry collections, which would you say are the main themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent themes of reference in your work?

I wouldn’t say there are recurrent themes of reference. If there is a binding thread of my presence so far, it’s my attempt to depict and convey a true feeling of the disability permeating our existence. The anti-heroic nature of another yet awakening. The siren of every minor and invisible ambulance that strives to save a shred of beauty. The shine of a knife as it repeatedly moves deeper to wound this beauty without managing to kill it. At times, I feel I have succeeded in doing so. At others, the vehemence of youth along with the lack of interactions have obstructed this depiction. Fortunately, life has its way to open up cracks of reflection, and even correction.

Vassilis Lambropoulos has argued that Greek poets have always had an overwhelmingly visual conception of the world, adding that “this phenomenon has been changing dramatically with the new poetry, because many of its writers are excellent musicians too and many others have impressive musical sophistication”. Is it possible, after all, for poetry and music to converse? Or else, where does the musician meet the poet in your work?

Poetry constitutes the deepest music of language. In turn, music is an art with its own high and fundamental value for humans. In Greece, poetry put to music constitutes, in opinion, a new artistic genre that combines poetic speech with music, at times with great results, at others at the expense of poetic speech. Our generation is looking for new ways for the two to converse, taking advantage of both the video and photography. I envisage a new art in the future, where the poetic speech and the musical atmosphere will converse in a visualized environment. And this is more than realistic. Since its infancy, poetry has always been interrelated with music, considering that it narrated the pain and greatness of humans fighting against the oblivion of non writing through melodies and musical motifs. It was a time that poetry came in handy in people’s every day life. At a personal level, given that I write and sing my songs, I cannot imagine my poetry set to music. On the contrary, I strive so that my songs have poetic lyrics.

“I am not one of those who approach poetry outside its historical and, more important, its social context”. What is the relation of poetry to the world it inhabits? What role is poetry called to play especially in times of crisis?

I don’t think that when someone writes a poem, he is called to play any other role than that of a real poet, that is a person willing to expose himself, feel embarrassed and tortured in front of a blank page striving to give birth to something bigger that himself. If he succeeds in doing so then automatically his era comes to reside in his words, an era much more truthful, deep and lively than the one doomed to reality. In my opinion, all times are times of crisis. Some are more transient, other more intense or bloodstained, while some other building on climaxes. There has never been and will never be a time of calm considering that human societies will always vibrate as long as there are challenges and obstacles to be overcome. That’s why the motif of lost Paradise is always present at the global subconscious as something that was lost and will eternally be longed for. Attempting an imaginary zoom throughout my 38 years of age, I have to admit that until I was 20 I could in no way expect to witness my country going bankrupt, a global pandemic, nazism, misanthropy and nationalism as a fashion and a power. I have been and am still hit by a violent slap of defeat, agony and anger whose sound reverberates in my books, as books of their era.

How do Greek writers relate to world literature today? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

As in all other fields, poetry is called to address people irrespective of national identity. Greek poets are fortunate to write in a beautiful and ancient language and at the same time quite unfortunate since this language is spoken and written by just a few million people in a world of almost eight billion. Nowadays, our generation is much more widely translated compared to the previous ones, not only due to its artistic quality but also thanks to the contemporary globalized reality. Unfortunately major Greek poets of the past were far less fortunate. There are indeed numerous and remarkable attempts so that modern Greek poetry moves beyond national borders, such as readings at top foreign universities and significant festivals as the Athens International Poetry Festival.

The 2010 financial crisis has ignited the interest of Europe and the US for Greek poetry, yet not always on purely poetic terms. The term “generation of the crisis”, which was broadly used to characterize the contemporary poetic production has, in my opinion, bestowed it with a conjunctural character it could certainly do without. In proportion to its population, Greece has numerous good poets, many of which are younger than 45 and are worth translating and reading irrespective of the crisis.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE