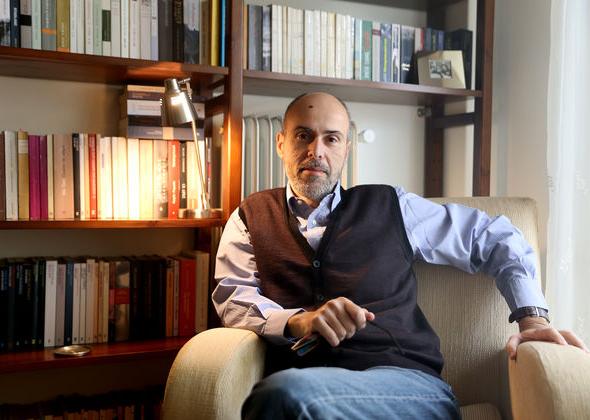

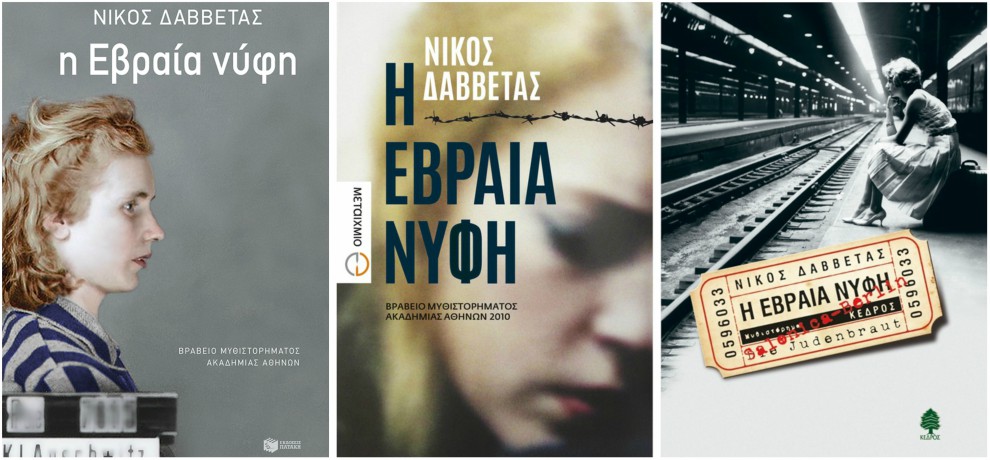

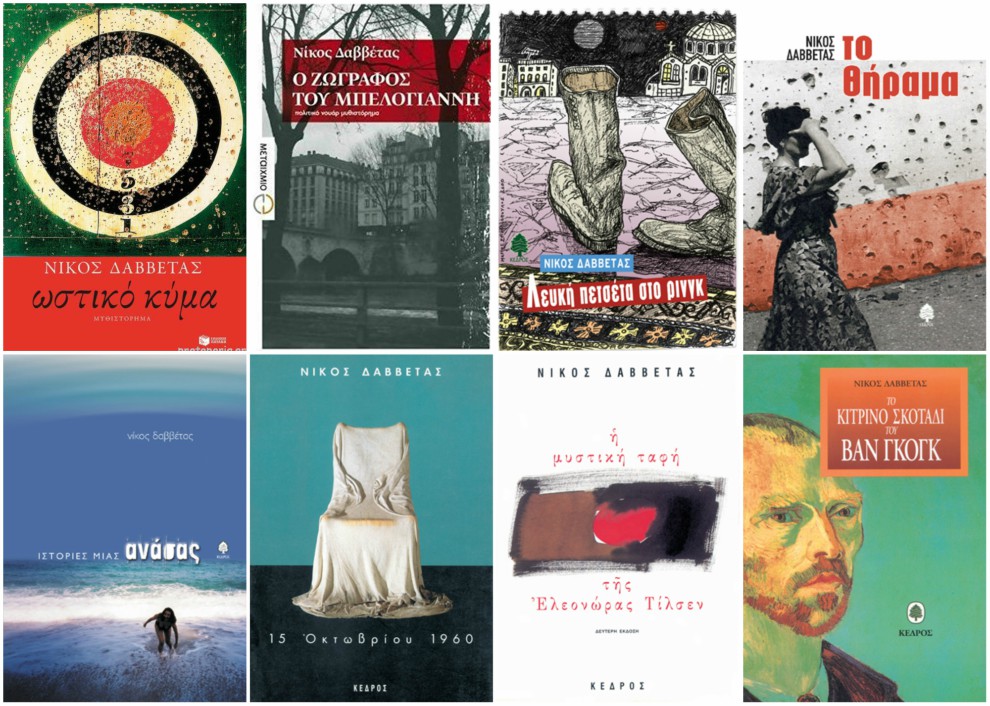

Nikos Davvetas was born in Athens in 1960. He studied journalism. He works as a literature critic. Since 2017 he teaches Creative Writing at Open University. He has published six collections of poetry, one collection of short stories and five novels. He has contributed to most Greek literary reviews; also he published essays and short stories in the literary magazines Waves (Canada), Agenda, Modern poetry in translation (UK) Partisan Review (USA), Erythia (Spain). Excerpts from his works have been translated into many languages, including English, German, Spanish, Hungarian and Swedish. In 2010, his novel Η Εβραία νύφη (The Jewish Bride) was honored with the Academy of Athens Award, and re-released in a newer version in 2019. His most recent novel is Ωστικό κύμα (Blast, Patakis 2016).

Nikos Davvetas spoke to Reading Greece* about writing as “a means of escape from the constant shortcomings of life […] into a version of reality more stimulating and tolerable”. Asked about his novel The Jewish Bride, he explains that the book “is not just another testimony on the Holocaust, but rather a modernist novel with number of innovations concerning the way in which individual stories and collective history are interwoven”. As for language, he notes that the language of literature is (has to be) “figurative, a language that transforms human experience into art”. He comments that in Greece “short narratives excel to this day, since they rely on a rich tradition”, and concludes that “contemporary Greek literature has no cause to envy that of Italy or Norway”.

Six poetry collections, five novels and one short-story collection. What drove you to writing and what continues to be your driving force? What would you say is the binding thread that connects these different forms of writing?

I am writing because I have not been reconciled with the reality around me; I write as a means of escape from the constant shortcomings of life. In this sense, the connecting thread of my writings is precisely the possibility through literature to create a parallel universe, to escape into a version of reality more stimulating and tolerable. Literature will always be for me “a door in the floor”.

Three publishers, an Academy of Athens award, a great number of reviews and The Jewish Bride seems today more timely than when it was first published in 2009. What is it that makes the interest in the book last through the years?

In 2009, when The Jewish Bride first circulated in Greece, we were all somewhat naïve, easily bypassing phenomena like anti-Semitism, populism, gender-based violence. Since then, the economic crisis, the financial memorandums, the emergence of pro-Nazi parties aroused public consciousness; readers were eager for narratives dealing with such issues. Still, The Jewish Bride is time-resistant, not only because of its topic, but also due to its style, a major concern in literature. This book is not just another testimony on the Holocaust, but rather a modernist novel with number of innovations concerning the way in which individual stories and collective history are interwoven.

“A novel doesn’t just narrate what has happened but what could have happened under specific conditions. In this respect, a writer should not just copy reality, but be a step ahead of reality”. What is the relationship of literature to the world it inhabits?

I am against making a plain imprint of reality in journalistic terms and earnestly in favor of fiction. The contemporary trend of making a novel some sort of documentary record of people’s problems, seems to me repellent

You have characterized literature as a big metaphor. What about language, and more specifically, the literary language? What role does it play in your writings?

The language of literature is not that of everyday communication, it is (it has to be) figurative, a language that transforms human experience into art.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

In 19th century Greece, the lack of a homogeneous urban tissue did not encourage the smooth evolution of the novel, as for instance in France or Germany; thus, for purely historical reasons, the short story became the major genre. Short narratives excel to this day, since they rely on a rich tradition. In essence, a novelist in Greece has no ancestors, just two or three names that joined modernism belatedly. Luckily, the novelists who appeared after 1990 in literary production have already created their own small tradition.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. Would you agree that in a country stricken by the crisis, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

In a certain way, the economic crisis made us what we really were but did not accept. I lost my job, but thus devoted myself more to writing, with less financial means, fewer amenities and escapes. I try to survive as a writer, yet, the Greek state taxes its writers the way it does doctors or tradesmen!

How would you comment on current literary production in Greece? Do Greek writers have the potential to move beyond national borders and attract foreign audiences?

Nowadays, except for two or three brilliant cases, literature written across the Western world is much the same, more or less. Contemporary Greek literature has no cause to envy that of Italy or Norway; unfortunately, adequate translators who could facilitate its establishment in some inhospitable editorial environment are rare.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE