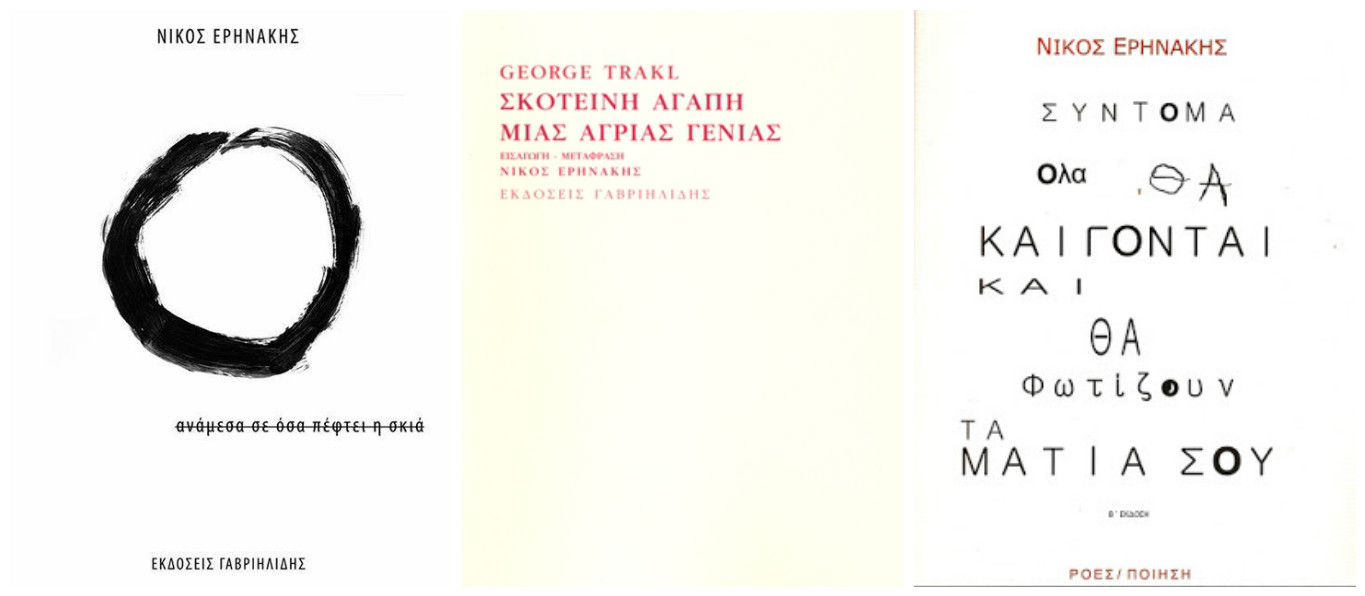

Nikos Erinakis (1988, Athens) is a Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy (Universities of London and Oxford), having studied Economics (AUEB), Philosophy and Comparative Literature (Warwick) and Philosophy of the Social Sciences (LSE). He has published two poetry books Σύντομα όλα θα καίγονται και θα φωτίζουν τα μάτια σου [Soon everything will be burning and will lit up your eyes] (Roes, 2009) and Ανάμεσα σε όσα πέφτει η σκιά [In between where the shadow falls] (Gavrielidis, 2013), as well as a translation of poems by Georg Trakl and passages by Martin Heidegger under the title Σκοτεινή αγάπη μιας άγριας γενιάς [Dark love of a wild generation] (Gavrielides, 2011). Essays and poems by him have been included in anthologies, have been published in numerous journals and have been translated into five languages.

Nikos Erinakis spoke to Reading Greece* about what drove him to poetry and what is his driving force noting that “what fascinated me, and still does, is the tension between voids and freedom, the quest of a poetry which the only ideal that recognizes is authenticity and beauty; away from a return to the absurd, but close to the configuration of the logical”. Asked about the interrelation between poetry and music, he discusses that “poetry should use all tools together in order to be exalted in the field of imaginativeness until it can become what it was born for or what gave birth to us: a game of beauty”.

He also reckons that “in the face of a contemporary post-modern drift towards a standardized instrumental mass society, it seems to me that through creative creation the possibilities of an authentic and genuine life may be awakened”, adding that “the breaking down of barriers between art and life, i.e. living creatively and thus authentically, may bring the quest of realising a thriving artistic culture back to the centre of poetic and philosophic inquiry”. He concludes that “poetry cannot remain simply a shelter, a lee or an escape; poetry can operate as a path towards a newfound reality. Inside there, in the great risk, we shall find salvation; the marriage, and not the assimilation, of oneness with the whole”.

You have published two poetry books, which seem as a quest for balance and sense in a world that has lost its pace and meaning. What drove you to poetry? And what is your driving force?

Beauty and pain. It was never a matter of choice; it was rather a matter of necessity. Many say that they write in order to be saved, not to lose their minds. As for me, writing does not save me, but rather, I guess, pushes more violently over the cliff.

What fascinated me, and still does, is the tension between voids and freedom, the quest of a poetry which the only ideal that recognizes is authenticity and beauty. Away from a return to the absurd, but close to the reconfiguration of the logical. It seems to me that a certain transcendental [with relation to the sacred and not the religious] range of thought and expression needs to be recreated, in order for us to cross the contemporary pause. We need to achieve the identification of poetic thought with stochastic poetry [as met, for instance, in the Presocratics]. Far away from the plain criticism and irony that characterize postmodernism, Ι feel that the aim of poetry is the development of a new imaginary. It seems the right time for poetry to suggest something novel again, to raise a proposition, to stop following life and convince life to follow her.

“Love, death and revolution. That’s where the game has always been played and will continue to be played”. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

From anything that I find authentic or to be a path towards authenticity. There is no reason to fear the big words, the hackneyed. I always tell to myself: Never put writing above experience. In other words, if you have to choose between being lost in the hair of a girl or inside words, choose the former. And also: never forget the crucial things; for example, what it means to be sun-kissed as, while randomly fooling around, you stare at a bougainvillea. Such are the ways to acquire an identity.

In any case, I consider critically important to read much more than I write. I constantly remind myself that one must write only when one has something new to say, otherwise silence sounds much better.

One, thus, needs to discover words that float above limits and give pace to anything silent that is ready to become something. Words that dig into the soil, seeking to express the urgent. These are the words that supply the necessary means to face the sky as an abyss below us, but also often leave us at the mercy of a strong propensity for silence. This is the kind of poetry into which our steps should burn. Chances are, nevertheless, that one shall most probably fail.

It has been noted that the influence of Odysseus Elytis and his Eternal Moment is evident in your poems both in terms of style and theme. How do you respond to that?

Really? That’s nice to hear—and perhaps it may be also right. But if one asked me about my deeper influences I would answer that my mind has more often got lost in ‘dialogues’ with words of the following literary ‘archetypes’: Heraclitus, Blake, and Rimbaud; Hölderlin, Trakl, and Celan; Keats, Pound and Eliot; Homer, Solomos, and Cavafy.

What role does music play in your life? What about the interrelation between poetry and music in your artistic ventures?

I am deeply interested in the conjunction of creative arts; and mostly, in the marriage of the pre-lingual (pre-Logos) and the lingual (Logos). The difficulty of the encounter and the discourse remains, and that is why the attempt of discovering its structure is based on the secret of the innate rhythm. For me, the only remaining solution is an appeal to the openness.We need an anti-biographic kind of poetry, which, at the same time, will be able to express the biography of us all—an ideal marriage between the individual and the collective. We need an experience of poetry that remains transcendental. We need to restore the experience of the sacred and the element of initiation. Beyond unnecessary manichaeistic dilemmas between logic and emotion, instinct and intuition, poetry should use all tools together in order to be exalted in the field of imaginativeness until it can become what it was born for or what gave birth to us: a game of beauty. In a nutshell, it seems to me that Dionysus is still around, and I ‘m trying to locate him.

“Even if inertia is against everything this word maintains, as it is able to lead to negative thinking, it can inspire us to be authentic, not follow the mass, be creative, autonomous and find joy into moments of complete freedom of thought”. Could you elaborate on that?

We find ourselves ‘thrown’, as Heidegger would say, into a world and a situation not of our own making, already disposed by moods and particular commitments, with a past behind us that constrains our choices. The “ethic of authenticity”, if radicalized, may provide us with more fruitful responses to the tensions of post-modern morality and enrich the answers generated by the more mainstream tradition of the “ethic of autonomy”. An authentic life is not one that can be simply discovered and then experienced; it is one that needs to be creatively created. In the face of a contemporary post-modern drift towards a standardized instrumental mass society, it seems to me that through creative creation the possibilities of an authentic and genuine life may be awakened.

One may choose between living a life based on what one rationally believes is best for one, i.e. a life in which one acts on one’s good reasons, and living a life based on what one creatively creates, regardless of whether it is good or bad for one, but with the certainty that it is truly one’s own creation. It seems to me that the breaking down of barriers between art and life, i.e. living creatively and thus authentically, may bring the quest of realising a thriving artistic culture back to the centre of poetic and philosophic inquiry.

It is through this creative openness to the yet unthinkable and unimaginable that genuine authenticity may obtain. There is no possible way to predict exactly what may occur through such a leap into the open and what its consequences could be, but this is also the main source of its beauty—besides, as Hölderlin writes in the opening verses of Patmos: “where the danger is, also grows the saving power.”

“More than a few can write masterfully but only a handful poetically. And what is missing nowadays is an unexpectedly unprecedented, but, most important, timely lyricism”. What role is poetry called to play nowadays? What about the new generation of Greek poets?

You can tell whether a poem is good or not, by noticing whether when you finish reading it, you have a tendency to change yourself or to change the world. Poetic writing of any kind educates; true poetry transforms—that is, I believe, a critical difference. The aim of poetry is not to explain the world, or slightly changed it. The purpose of poetry is to make the world its own—to transform the world into itself.

At a time when language has been exhausted we cannot keep giving away our most beautiful words leaving their meanings and semiotics to the vulgarians. We need to create new symbolic forms for our individual and collective ideas and actions. A poetry that is not just language; it is simultaneous contact with the pre-lingual and post-lingual stage. Poets of a certain height have proved the feasibility of a revival of the language. Such a possible regeneration could regenerate our imagination too, and that would allow us to visualize and thus to induce the regeneration of our reality. Poetry cannot remain simply a shelter, a lee or an escape; poetry can operate as a path towards a newfound reality. Inside there, in the great risk, we shall find salvation; the marriage, and not the assimilation, of oneness with the whole.

Whether the contemporary Greek poets of the new generation are indeed capable of winning, or even taking part in, such a high bet, remains an open and tricky question. In any case, fortunately or not, we live in interesting times–we shall, thus, see.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE

![Literary Magazine of the Month: [FRMK] and its Ten-Year Anniversary Issue ‘Tenderness-Care-Solidarity’](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/04/frmkINTRO2-1-440x264.jpg)