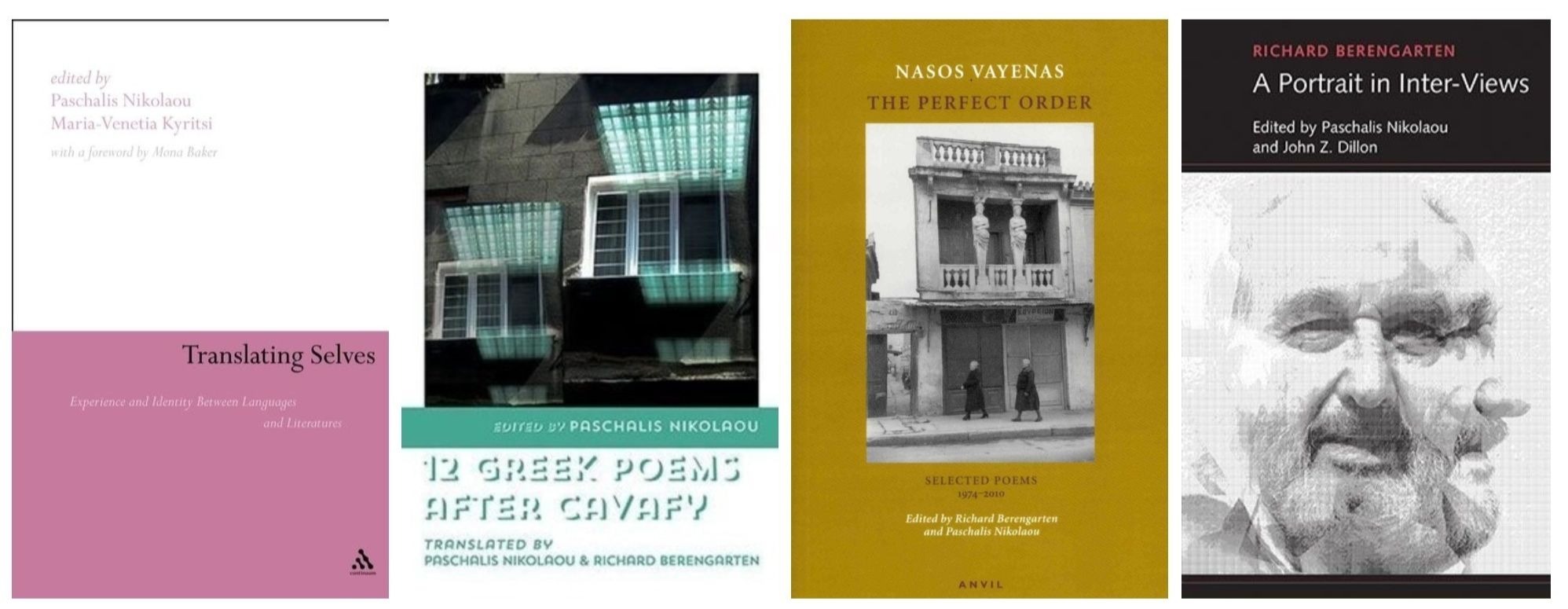

Paschalis Nikolaou is Assistant Professor at the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting of the Ionian University, Corfu. His writings on translation studies have appeared in such publications as Translation and Creativity: Perspectives on Creative Writing and Translation Studies; reviews and translations have been widely published in journals in Greece and abroad. He is the editor and co-translator of 12 Greek Poems After Cavafy (Shearsman Books, 2015) and has co-edited Translating Selves: Experience and Identity between Languages and Literatures (Continuum, 2008), The Perfect Order: Selected Poems 1974-2010 by Nasos Vayenas (Anvil Press Poetry, 2010), a volume shortlisted for the Criticos (now London Hellenic) Prize, and most recently, Richard Berengarten: A Portrait in Inter-Views (Shearsman Books, 2017). He is currently reviews editor of the academic journal mTm, consulting editor to the International Literary Quarterly, as well as a regular contributor to the Greek literary journal Nea Efthyni.

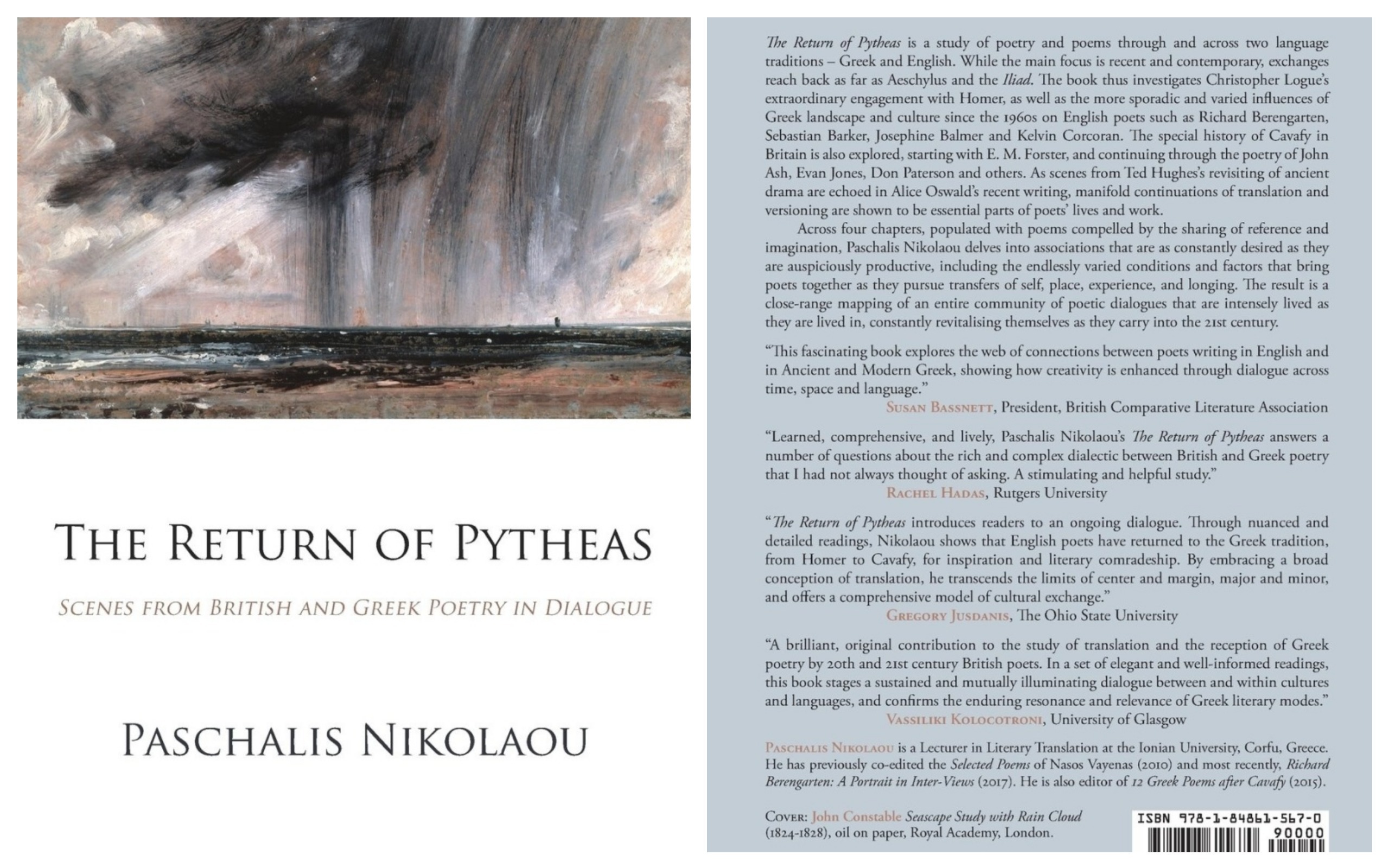

His most recent book titled The Return of Pytheas: Scenes from British and Greek Poetry in Dialogue (Shearsman Books, 2017) is a study of poetry and poems through and across two language traditions – Greek and English. While the main focus is recent and contemporary, exchanges reach back as far as Aeschylus and the Iliad. Across four chapters populated with poems compelled by the sharing of reference and imagination, Nikolaou delves into associations that are as constantly desired as they are auspiciously productive, including the endlessly varied conditions and factors that bring poets together as they pursue transfers of self, place, experience, and longing. The result is a close-range mapping of an entire community of poetic dialogues that are intensely lived as they are lived in, constantly revitalizing themselves as they carry into the 21st century.

Paschalis Nikolaou spoke to Reading Greece* about The Return of Pytheas commenting on the encounters between Greek and British Poetry, as well as on the reception of Greek poetry – both ancient and contemporary – by 20th and 21st century British poets, and, their impact on Greek literary production. He talks about the challenge of moving beyond long-standing stereotypes and the contribution of poetry to this end, while he also discusses the role of translation in the diffusion of literature beyond national borders. He concludes that “there is much to accomplish still in improving, coordinating, and deepening, exchanges”, noting that “improved results will come from forming networks of universities, and through systematic discussions between them, state structures and private bodies in the future“.

In your latest book The Return of Pytheas: Scenes from British and Greek Poetry in Dialogue, you comment that “the figure of the ancient Greek seafarer comes to symbolize a rich panoply of encounters: of a poet with another land and people; of expressions and revolutions in verse of the experiences of travel, long stays abroad and relocation”. Tell us about some such encounters between Greek and British Poetry.

Αbove all, it serves as a reminder to us that in both traditions, themes of exploration were always strong. There is closeness to the sea; our history is also a maritime history. And of course, in some British poets, we come across actual references to the figure of Pytheas, direct treatments. We soon realize interesting contrasts, or rather, interesting asynchronies – in Empire and post-Empire Britain, or a modern Greece that is too often (mis)understood in relation to the classical world, and its inheritance. Some relationships may seem lopsided; the one with Homer going back to Chapman, imports and negotiations of modernist values through Seferis and other poets of his generation.

When it comes to Greek (cultural) space, poetic dialogues are entangled with notions and experiences of travel. Even before Byron, visits to Greece coincide with diary records, dramatizations – and of course, poems. In The Return of Pytheas I am attempting, for the most part, to look at a number of cases post-1960. There are poets who have built a steady relationship with certain regions and islands after long stays in Greece. Sebastian Barker or Kelvin Corcoran for instance, the latter even producing an anthology of Greek-themed poems. British influences, place-names can be found in poets like Nasos Vayenas or Haris Vlavianos but also in the writing – the structuring of collections even – of poets who’ve been to Britain post-1990, often initially as students. Krystalli Glyniadakis comes to mind.

The underlying intention here, of course, is also to ask ourselves about boundaries and borders, interpenetrations which may have already happened: because there are also poets of Greek ancestry who write in English and publish their work in Britain, like Alice Kavounas or Fani Papageorgiou. Τheir poems often contemplate what it means to be Greek, half-Greek, living abroad, pursuing connections with individual and collective memory. So these dialogues can be many-sided, and often internal. On the other hand, there’s a deep, ongoing relationship with Cavafy in poets like Josephine Balmer and Christopher Middleton; again, Vayenas’s resourceful re-transmitting of Gavin Ewart; several of these dialogues happen through translation, or variously reconsider its practices.

How would you comment on the reception of Greek poetry – both ancient and contemporary – by 20th and 21st century British poets? And, in turn, what has been the impact of British poets on Greek literary production?

The impact of British poets is perhaps more diffused, a bit harder to assess. Τhough you can certainly trace resulting inflections and re-arrangements in Dionysis Kapsalis and, from the poetic voices emerging in recent years, the work of Maria Topali, Thodoris Rakopoulos, Katerina Iliopoulou and Yiannis Doukas. A sense of discipline in composition, renewed interest in formal features and narrative appears to follow such encounters (often initially taking the form of translation). Their products are well spread – which means there’s still much more for us to study here – in journals like Poiitiki, Nea Efthyni or Odos Panos. I am talking about the recent past, of course, because shifts occurring in the wake of literary modernism are well-studied. But even earlier, there are such scenes: for instance, Cavafy attempting translations of Tennyson, Shelley and Keats in the 1890s.

British poets – I mentioned this earlier – have been aligning with Homer for centuries, with three notable examples in the 20th and 21st centuries being Logue’s War Music, Walcott’s Omeros of course and Oswald’s more recent Memorial. Dramatic works, Sophocles and Euripides in particular, have appealed to Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney and Simon Armitage.Τhe result can be staged performances, or meaningful fragments embedded within individual collections, in dialogue with original poetry.

Then there’s the example of Cavafy which is absolutely unique, not only looking at the incredible number of book-length editions, especially post-2001, but also translations done by poets like Don Paterson and John Ash, as well as Cavafy-inspired poems, even collections of poems. Seferis and Ritsos recur less in this sense, but we still come across negotiations of style and themes in a sequence like Richard Berengarten’s Black Light: Poems in Memory of George Seferis, published 35 years ago. Τhe Greek translation, by Vayenas and Ilias Lagios appeared in 2005. David Harsent has put out some mesmerizing versions of Ritsos. I haven’t seen any engagements with Elytis for some time, though the late Sebastian Barker was fascinated with him and often channeled him into his work. Greek poets writing today are even less visible.

David Connolly supports the idea that “many contemporary poets who have failed to make an impact in English translation have undoubtedly suffered from the legacy of Greece’s ancient past and from a particular perception of Greece by Westerners”. How challenging is itto move beyond long-standing stereotypes and form a new imaginary about the country? Could contemporary poetry help to this end?

It is worth noting that Connolly discusses this in introducing his English translation of Yannis Kondos’s collection O Athlitis tou Tipota (1997), itself an example of ‘best practice’, of how to conquer certain problems. Absurd Athlete was a bilingual edition, published relatively close to ‘real time’, and within a series of books of contemporary poetry – Arc Publishing’s Visible Poets, still going strong – that took particular care of details that matter. There’s a point to make, incidentally, with respect to what counts as modern or contemporary verse, for readers in other languages and traditions. Τhe translated Seferis, Fokas, or Anghelaki-Rooke are in some respects nearer in time to the Anglophone reader than they are to us. We need to synchronize our watches a bit more. There aren’t as many examples like Absurd Athlete as we would like (but I happily note the recent translation of Phoebe Giannisi’s Homerica), that is, in terms of us thinking beyond a possible Selected Poems, more assertively situating the translation of a poet who is writing in the here-and-now. In 2018, several Greek poets have produced work worthy of this treatment. When it comes to stereotypes, the visual aspect too can be important: we resisted – the poet also – a blue cover initially suggested to us by the publisher for Vayenas’s Selected Poems. (The final cover was exactly the same, but a shade of brown instead of blue.) One realizes how very many book-covers of translated poetry from Greece use blue. Even such colour-codings – or other visual shortcuts – activate a set of responses, and resupply readers with stock images, well into the 21st century. I suspect that until we move beyond a stage of anthologies, a few poets rising above current groups, with recognizable, individual themes and formal concerns, it’s going to be naturally easier for editors or publishers to suggest – or impose – a direction. I’d rather have a particular poet’s perspective, sense of things (not necessarily of Greece) emphasized, a poet that happens to be Greek.

What is more, we’ve noticed in the past that when there’s survival of poetic voice(s) beyond a given frame, beyond the initiatives – commendable as they are – of translators, editors, publishers and so on, this is often precisely because their verse becomes transfused, assimilated, imitated, re-expressed by fellow poets. This would be the case of say, a Cavafy-inspired poem written by Christopher Reid or Evan Jones, who have clearly read Cavafy in translation first. Again, there’s an extra step involved here; when translation leads to something else. Not many poets have endured simply by virtue of their presence in ‘translation proper’. Other echoes, filtrations are necessary. When we start reading poems ‘in the manner of’, then we’re on to something.

Theodoros Chiotis claims that “this particular historical circumstance might be a once-in-a-generation opportunity for contemporary Greek literature to be diffused outside Greece”. Yet, could contemporary poetic voices extend their presence in English beyond the current socio-political frame?

Arguably there are already some distances involved, yet even when the effects of the crisis on Greek society were overwhelming, poetic writing was not decisively bound to social and political circumstances.Poetic voices can extend their presence beyond this sort of frame, and if anything, they must – poetry strives for a different kind of duration, I think. Particular events, behaviours intensifying in those years, are naturally reflected in some form in the literature produced in the period. I believe it happens more effectively in prose fiction than in poetry. Even so, some poets have focused on the socioeconomic crisis in parts of their work (and many more spoke about the crisis).

There is, inevitably, poetry written during the crisis. Whether it’s thematically, formally, tonally different enough from what has gone on before…that’s a harder point to argue. One dominant mode includes disjointed aphorisms, an often unearned lyricism that may even be counterintuitive to absorbing and truly describing the impact of events. On the other hand, when one is editing a book, and working out the ideas and structuring principles behind it – this can sometimes be more clearly part of the poetry of its time. The book enters a critical legacy of the period, and may reveal the way we see, or want to see, ourselves.

I think it’s preferable to consider larger categories, and if one does that, the time soon comes to champion specific poets, to progress beyond groups. And several groups were indeed formed during the crisis – that’s true. Again, ‘opportunity’ is not a word I would use, though I can sense how it is primarily meant; and I agree with Chiotis when he suggests that there needs to be a more consistent book policy, a more intelligent approach to getting people excited about contemporary poetry from Greece. It is, however, a long game; it will take time for a small set, of 2-3 poets to have their names truly recognized outside of Greece – for them to enter, really and consequentially, a literary elsewhere.

When translating from a so-called “minor” to a so-called “major” language or literature, translators do sometimes hold remarkable power, including the power to produce what will in many cases become the only interpretation of a work of literature available in a given language. How do you respond to this power?

Well, it’s true. In most cases, a poet will only get one shot. Cavafy is the exception to the rule perhaps, but we’ve long passed the point since he became part of world literature. Literatures in major languages may often be voracious, but attention-spans can be limited – and sometimes this applies to key poets, Nobel-winners: even recognition on that level won’t necessarily guarantee a continuously maintained existence in this or that literary or cultural memory.

In terms of translation, any such project attempts to take into account several, often competing, intentions. And there’s always a balance to be struck between verse that is representative of someone’s work – those key poems that unquestionably should be repeated across languages – and some titles that lend themselves particularly well, to, say, English or Spanish. Translators need to be involved, I feel, in most aspects of a book’s presentation and reception, including, as I mentioned earlier, the cover. Paratexts, their combined length and balance, need to reflect a good understanding of our intended readers, the amount of information they will normally seek, or be able to absorb. Emphasizing or clarifying intertextual relationships is often a priority.

Even more so in the case of a Selected Poems, there are connections and analogies that readers may be encouraged to pursue. For a poet like Vayenas, whose work I co-edited and co-translated some years back, it was crucial to communicate to English readers his activity as a critic, so Richard Berengarten and I thought it was important to include a brief selection from Vayenas’s essays. And a bilingual chapbook of Greek Cavafy-inspired poems I edited in 2015 also was a chance for English readers to glance at some little known Greek poets.

Overall, one needs to be patient, in so many ways, during the making of a translation and what surrounds it – even more so in cases of collaboration; and then stay involved in variously ensuring this work remains visible, long after it has been translated and published, of course. And yet, one may do everything right – and I’ve witnessed this often – the writer can be truly important, and still not much happens; the moment passes. So, at the very least, you want to be very capable and active in a number of areas, beyond actual translating – as translators, our work is often very close to that of an editor or literary critic, and this is something we also try to communicate to students of literary translation.

In your book you conclude that “there is much to accomplish still in improving, coordinating, and deepening, exchanges”. Could you elaborate on that?

Certain organizations, the Onassis Cultural Centre or the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center for instance, are already doing great work in encouraging dialogues between scholars and poets. A rejuvenated Greek National Library (which has recently moved to the Faliro bay site of the Niarchos complex) has given signs of an ambitious schedule of events, which will hopefully include future invitations to writers working abroad. And there have also been efforts already in managing Estates and Archives of Greek poets. When done right, this kind of activity enhances our knowledge and leads to more consequential dissemination of work – especially when it comes to some key, yet lesser-known names. New discoveries often occur, when drafts and manuscripts are ordered and digitized – and such processes can later be connected to translation. We sometimes think the position of a poet within a culture is stable: non-improvable – or unassailable. But that’s precisely where translation begins. Nor is it just the younger poets that deserve our attention. Re-examinations of tradition, appreciating anew – first of all within Greece – the significance of a number of 20th century poets (Zisis Oikonomou, for instance), republishing them … These are steps that should never really be ‘skipped’.

There used to be some funding programmes, like the often-lamented ‘Frasis’, suspended during the years of the crisis. Re-instating a version of it could be crucial, and ideally, more financial sources should be directed expressly towards translation from some of the private institutions too – involving, even, stable collaborations with publishers abroad: it would be interesting to have a series of books by Greek poets, with a recognizable design and with a solid team of editors/translators attached to it. So it’s not necessarily a case of returning to anything as centralized as just one, state-run programme. Yet this is an environment where co-ordination through the entire chain is truly important, from early presentations of translations, to launching and promoting published books.

There are also certain prizes and awards that draw attention to Greek literature and its study, such as the Runciman, the London Hellenic Prize, the Edmund Keeley Book Prize… The first two sometimes honour translations, but it would be even better once again to see a prize dedicated to translations of Greek literature into English.

Finally, to my mind, few things work better than finding ways to have writers, scholars, and if possible, translators, around each other. A small literary gathering, a ‘summer school’ or ideally, a festival like the one we hosted at the Ionian University in October 2017, when we invited four Irish and four Greek noveliststo Corfu. This kind of event creates a wealth of connections, inspirations, and even sometimes, unexpected collaborations. It may still include academic sessions, book launches, roundtables, various workshops. Early translation efforts and contacts with publishers can all happen in this context. Depending on interesting funding bodies of course, I know there’s no lack of organizations and venues that would host such events; the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting where I’m based, certainly pursues such opportunities. Improved results will come from forming networks of universities, and through systematic discussions between them, state structures and private bodies in the future.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE