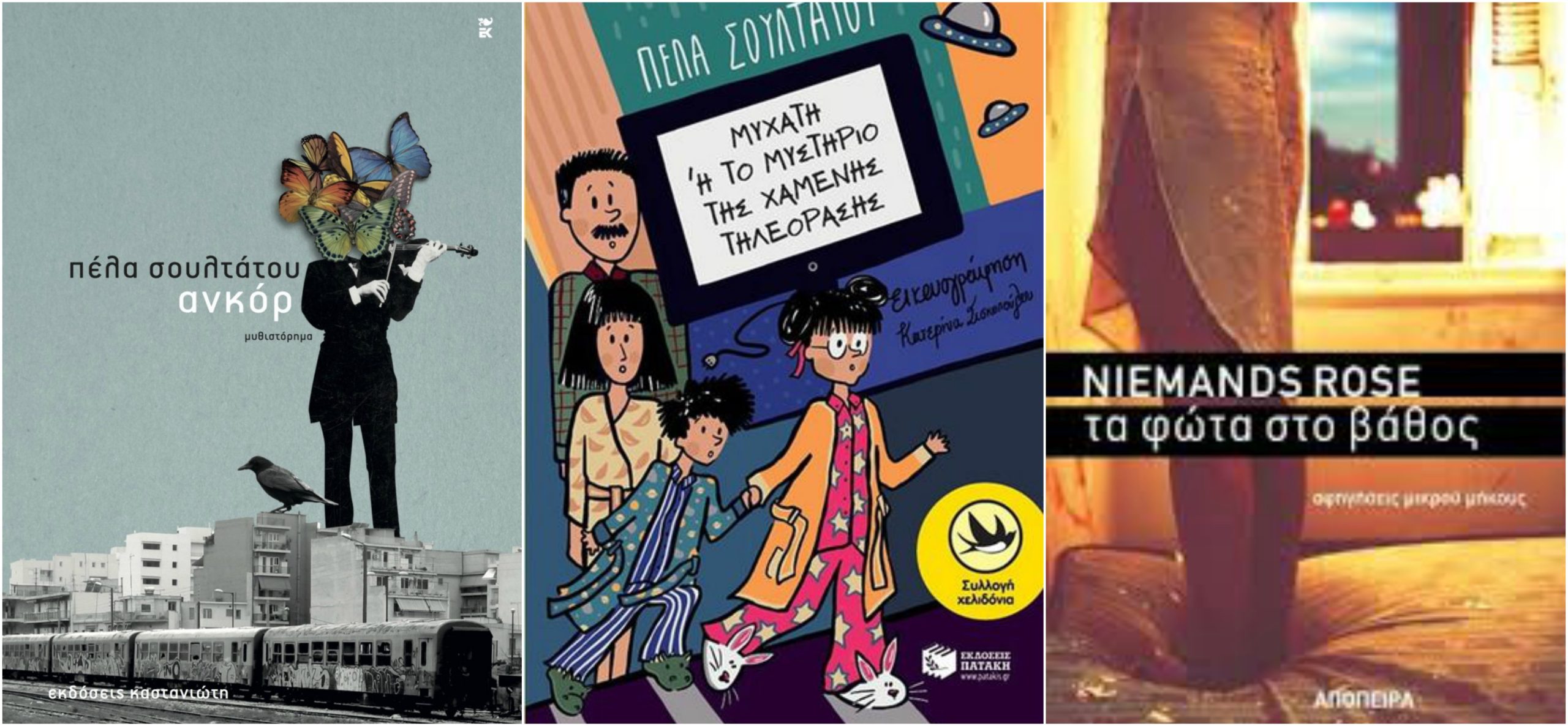

Pela Soultatou has studied Sociology, Community Health, Health Promotion and has earned a PhD in Education from King’s College London as a scholar of IKY (State Foundation of Scholarships). She has published two novels Ανάποδες στροφές [Reverse Rhymes, Kastaniotis 2019] and Ανκόρ [Encore, Kastaniotis 2015]; a book for children ΜυΧατή ή το Μυστήριο της Χαμένης Τηλεόρασης [MyLoT or the Mystery of the lost TV, Patakis 2019); and a collection of short stories Τα φώτα στο βάθος [The lights in the background, Αpopeira 2016] that was dramatised in the theatre.

Pela Soultatou spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest writing venture, noting that “it constitutes an experimental endeavour”, “released from the burden of intentions”, where language is “a combination of three idiolects”, “the contemporary slang”, “an outdated jargon” and “a hint dialect being spoken in Crete where the story takes place”.

Asked about whether Greek writers prefer short forms to longer narratives, she comments that “the large proportion of readers are more apt to grasp these bulky and heavy books from those large bookstores”. As for the potential of the new generation of Greek writers to attract foreign audiences, she explains that “we are trapped in a language spoken in just two countries of all planets” and concludes that “the Greek editors-just like most Greek entrepreneurs not seem very keen with the idea of translating and exporting our domestic intellectual products abroad”.

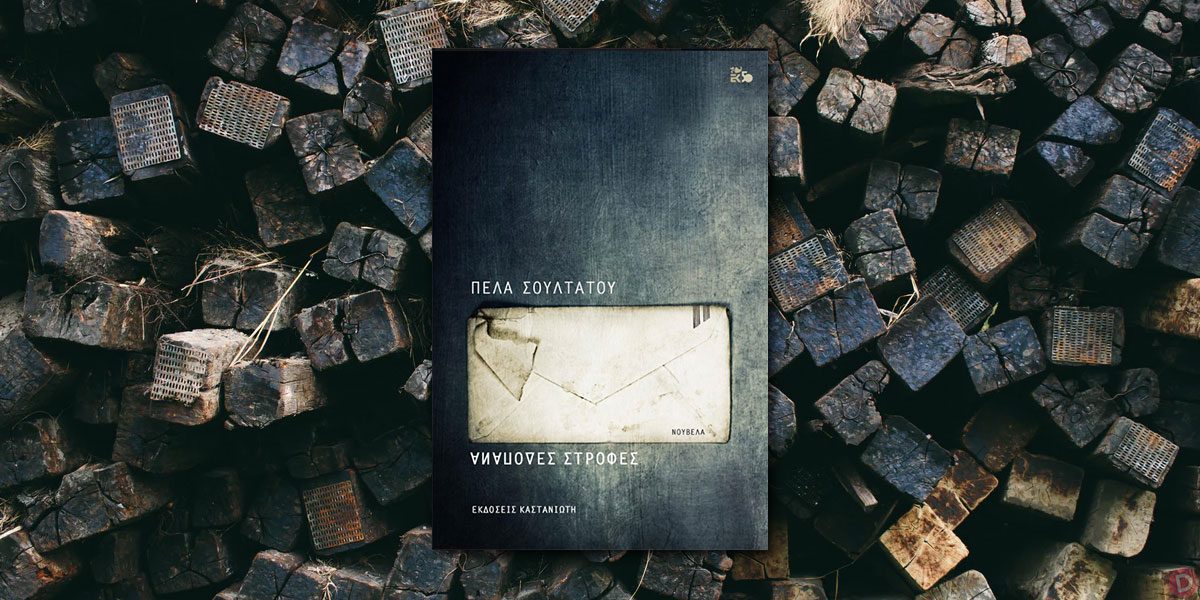

Your latest writing venture titled Reverse Rhymes received rave reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

This novel emerged through another larger piece of writing, which was then scrapped. So in a sense, it constitutes an experimental endeavour. This left me a considerable degree of freedom to develop a story out of nowhere, released from the burden of intentions.

My third book is intermingling the holy family with the Greek family, to describe in depth, but in a rather satirical manner, the peculiarities of a single mother with her only son relationship. Hence, I invented a reverse Virgin Mary and a reverse Jesus Christ. Mary, the mother, has been a sexually overactive woman who does not seem to see her son as a brilliant, charismatic and virtuous person, as usually is the case in our mediterranean families. Likewise, her son Manolis (a diminutive of Emmanuel, the foretold name of the Messiah in the Old Testament) is quite the contrary of what we have in mind as features of Jesus Christ’s personality.

During New Year’s eve, Manolis is out with friends, but totally broke. He finds an excuse to drop in at his place and search for his mother’s hoard, while she is spending time at a friend’s miserable party. Manolis is looking for the “treasure” in every single part of the little flat, when he discovers his mother’s personal diary. He is tempted to read it and the “dark side” of his mother’s face is revealed. From that point on, the time is reversed and the plot resembles -but again in a satirical way- crime fiction.

Your language is quite powerful in its realism and bluntness. What role does language play in your writings? How is raw realism combined with magic realism in your books?

I embarked upon a combination of three idiolects, the contemporary slang spoken by the 18th years old Manolis, an outdated jargon spoken by his mother Maria in her 40s and a hint dialect being spoken in Crete where the story takes place.

But what I find challenging is that I let the narrator being influenced by the characters’ language. In this sense, the style does not change dramatically from the hero to the writer, but the second follows the first although in her own way. I have experimented with this in my previous novel, “Encore”.

The book touches some key social issues, such as patriarchy, domestic violence and the place of women in modern Greek society. Does literature offer a way to deal with such issues and help societies move a step forward in this respect?

To be honest, I had no purpose to teach anything to anyone about what it means to be a single-mother in a deprived neighbourhood and yet wishing to indulge into carnal pleasures but to live decently, as Maria, my main character, does. I had no plans to help the society understand what it means for a youngster to be a real NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) obliged to join the army in a while and encountering the dark side of his mother’s face. I wished to tell a story and this what I did; hopefully well.

You have experimented with various forms of writings: from scientific articles to novels, novellas and black comedy. Would you say that the theme dictates the form? Is there a binding thread?

It’ s like having a garden with different sorts of flowers and plants. I do what I have to do with each one of them, I water them, I trim the down and so on. Maybe I don’t have all the time of the world to take care of them equally, and at times I focus on one particular kind, to be honest. However, I feel it is more colourful and fragrant like this. Unusual though, I know. Readers and critics prefer you to represent just one, max two, different forms. But we take our risks in life, in order to fulfil our desires. I could not do otherwise. On the occasion, I wish to add to the list above a book for schoolchildren I have recently published.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

Now you trigger my academic side, which means that I cannot actually comment on this without having a set of data. I am not quite sure this is the case. On the contrary, I think that the large proportion of readers are more apt to grasp these bulky and heavy books from those large bookstores, feeling that they afforded for something big that worths their money. There are, of course, those few who still prefer quality to quantity, we almost know them by their first names in our little book-lovers’ community. But we live in capitalism, difficult to survive in the contest with the market.

Writer Nikos Mandis has argued that “the novel is one of the means that will enable Greece to enter a broader map and communicate with people beyond its borders”. Does the new generation of Greek writers have the potential to attract foreign readers?

I have not read the whole of Niko’s thought, so I am ambivalent as what exactly he means by that. It sounds pretty optimistic and I would love to share this view. But it is true that we are trapped in a language spoken in just two countries of all planet and the Greek editors-just like most Greek entrepreneurs not seem very keen with the idea of translating and exporting our domestic intellectual products abroad.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE