Pelagia Fitopoulou was born and raised in Katerini and currently lives in Athens. She began her studies at the University of Athens (pedagogy), while she also studied journalism. She graduated from the Iasmos Drama School. She attended seminars on narrative acting and direction, as well as on Suzuki Actor Method based upon of Tadashi Suzuki. She acted in theatre, television and cinema. She founded the theatre group “Sirius” and staged plays on human rights, violence in education, poems and fairy tales. In 2015, she presented Ionesco and Athayde in a German theatre. Her poems have been translated into Italian, Finnish and Albanian.

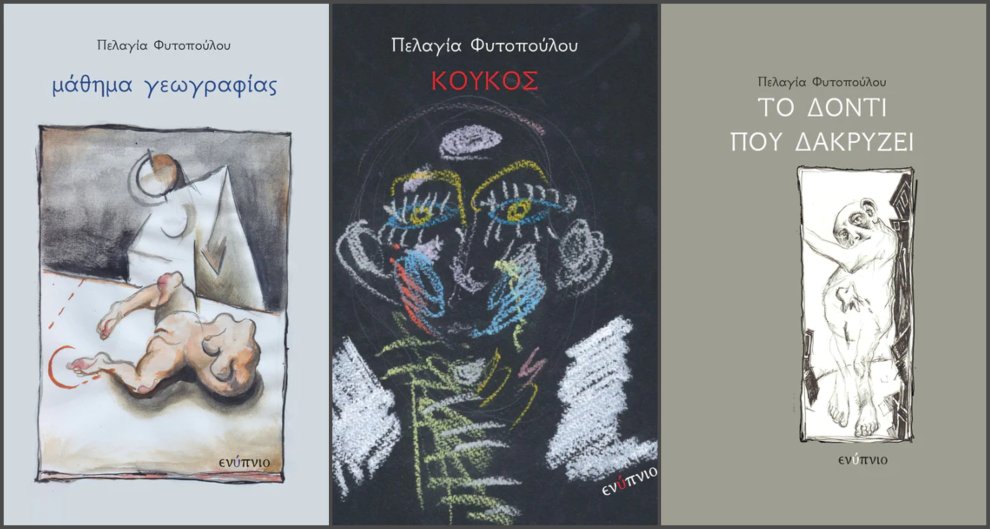

You have published three poetry books so far. Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

I was a happy child. After all, isn’t that a child’s job? Happiness? I soon realized – let’s keep that word – that I was wrong. The children around me were sad, almost unhappy, and I decided to find out why. I was a child, I had time. I became an observer. Why? Many say that trauma lives in the heart of Art and when you don’t have your own, you borrow! What I found was Violence and it shocked me. The violence that a person falls victim to from the moment he/she is born until his/her death is something that surpasses me, something that haunts me.

So, violence is one of the main themes my art is concerned with. Domestic violence, social violence, political, verbal, class, educational, romantic violence, violence in all its aspects. But I don’t lose my courage and I hope, as I grew up with love, I hope for freedom and I always write about it: the battle of justice, that person who resists, that one, always alone, the free person. The fighting person is an amorous person. Indeed, it is repeated here and there in my writings, but not as a crutch to express my opinion on life – this is not my job – it is life.

Υour poetic language is quite tough, with an orality that is tailored to the era it pertains to. What role does language play in your writings?

I smile, you know, when they ask me if my poetic language is harsh. Is there a soft one? That is, we accept that there are beautiful words, ugly words, tender, dark, unpleasant, immune, delicious ones. Do we accept this distinction? Poor words, rich words, like rich people, poor people; I consider this to be a kind of violence, and certainly a violence harsher than my poetry. Words are words, unsuspecting andoblivious, like newborns.

Each word constitutes a fascinating world, difficult, thankless perhaps; it is a branch, and the branches are not all the same, but they all together make the tree. That is, language. And there is nothing more defenceless than a tree and a dead man. Maybe… Language is very important in my poetry, it is my poetry, it is the soil I tread on. And sometimes I dig deep with my hands and hurt it, but maybe I get hurt too. Is that lyrical enough?

How does literature relate to the world it inhabits? Could literature be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

For this question I will ask the help of Orson Welles and convey some things he said in a lecture to students in Europe shortly before he died. “Everything is a story, the world is a story, you can’t make cinema, literature, music, art without a story… except Fellini”, he said jokingly. Life and art are inseparable. The whole world is a story and a story is made up of its people. Tell it… Now, I don’t know if there are different roads, but I feel that there are alleys and narrows that whoever dares to cross them, will surprise and be surprised.

Since you are also actively involved in the theatre as well, where do theatre and poetry meet? What is their binding thread?

I owe poetry to theatre, love to poetry and freedom to love. That’s how indissoluble their relation is. The first thing you come into contact with in the theatre is poetry. Where should I start: from Aeschylus the great father, Sophocles, Euripides; and where to get to: Lorca, Beckett, Chekhov, and, and so on…The way actors get into texts cannot be achieved neither by philologists nor by linguists.

Poetry becomes their everyday life; I would say that it acquires an addictive quality, it becomes a heartbreaking situation you cannot easily get rid of it. That’s why I always give my poems to actors and directors to see first, then to poet friends and never to philologists. And because theatre is going through tough times at present, let me just quote Federico García Lorca: “Theatre is the school of the people”

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. In other words, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule. Could things be otherwise?

The other day, my publisher called me to pay me my copyrights, and I replied, ”are you really going to pay me?” Of course, we don’t live from our intellectual work in Greece. It’s quite rare and mostly happens to prose writers. Understandable. The audience for art is small, let alone for poetry. The same goes abroad. I don’t believe that poets have got rich, things are just a little better. In Greece, there is no interest in the book, especially on the part of the state, and the same goes for most arts. Theatre is a case in point. And, of course, let me not touch on class issues; people facing hardships cannot easily touch upon artistic paths…I am far from optimistic about the future. What can really change? Is any of us willing to change? Because we expect everything from the above.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, festivals, just to mention a few. How is this strong civic awareness to be explained?

There is an extroversion after the crisis. Let’s not forget the shock the country suffered. It was only expected that whereas before the crisis group arts were at their peak given that there was money, when money was no longer available, solitary arts flourished. In other words, putting on a theatrical play or making a movie is an expensive sport, it needs a lot of money. On the other hand, going out on the streets and reading poems doesn’t need anything. I have myself participated in similar events. I am neither negative nor positive, I just see the reason why.

When I was doing theatre before the crisis, I worked all year long to be able to express myself for ten days. Such a short time, you would say, but we could do it; I felt truly and absolutely alive. It was hard work for just ten days of life, love, but it made me feel alive. And then came the crisis, and theatre and dance groups almost disappeared and we disappeared as well, we suffered. And those of us who were lucky enough to have some other art in our luggage, we dared to things that we might have scoffed before – to read a poem, say, in a bus, someone gave me one euro for my trouble!

As if I was a beggar after 15 years of study – and yet you can’t stop being who you are, an artist; some flowers will bloom on rocks too.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

INTRO PHOTO: @Stathis Intzes

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE