Phoebe Giannisi, born in Athens, is the author of six books of poetry, including Homerica (Kedros, 2009) and Rhapsodia (Gutenberg, 2016). She also holds a PhD in Classics from Lyon ΙΙ-Lumière published as Récits des Voies. Chant et cheminement en Grèce archaïque (Grenoble: Editions Jérôme Millon, 2006). Her work focuses on the borders between poetry and performance, installation, theory and representation, and investigates the connections of poetics with body and place. A 2015–2016 Humanities Fellow of Columbia University, Giannisi is an Associate Professor at the University of Thessaly.

Selected group exhibitions include the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark (2011), Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Budapest (2010), the Lyon Biennale (2009), Guggenheim New York (2013), Bauhaus Dessau (2015). In 2010 she was co-curator for the Greek Pavilion of the 12th International Architecture Exhibition (La Biennale di Venezia). In 2012-13, her poetic video/sound installation about the Cicada, TETTIX, was exhibited at the Museum of National Art (EMST), Athens. In 2015 she exhibited her work project about Goats AIGAI_O at the Angeliki Chatzimichali Museum in Athens (with Iris Lycourioti). In October 2016, she presented her performance/lecture Nomos_The Land Song at Onassis Center, New York.

Phoebe Giannisi spoke to Reading Greece* about the way her poetry evolved over the years, noting that for her, “making poetry means admiring language; being moved by, meditating on, listening to, searching through language”. She comments that a crucial question posed in poetry is “in Socrates’ words, to know oneself, the poetic self, that speaking voice in a poem”, adding that “poetry is but a response to stimuli, which touch, permeate and agitate the body”. Asked about the meeting point between poetry and the natural world in her writings, she explains that that “the so-called ‘natural’ world is [her] window to poetry”, that “the bodily senses are mediated by their expressiveness through constructed language, which means poetry or philosophy, the first ax that dug this world”.

She concludes by commenting on the current literary and artistic production in Greece, noting that “nowadays art in Greece witnesses the advent of many significant and positive elements”, that “a new form of art is thus happening, claiming the “commons” in general, against discriminations, and connected to practices of care for the other and for the weak whether it is human or nonhuman”. “I firmly believe that poetry is a field of freedom that constantly redraws itself and its boundaries. Poetry is not just a subject but a way, poetry is a becoming […] Yes, poetry can be a revolutionary therapy since it is written with no usable value whatsoever”.

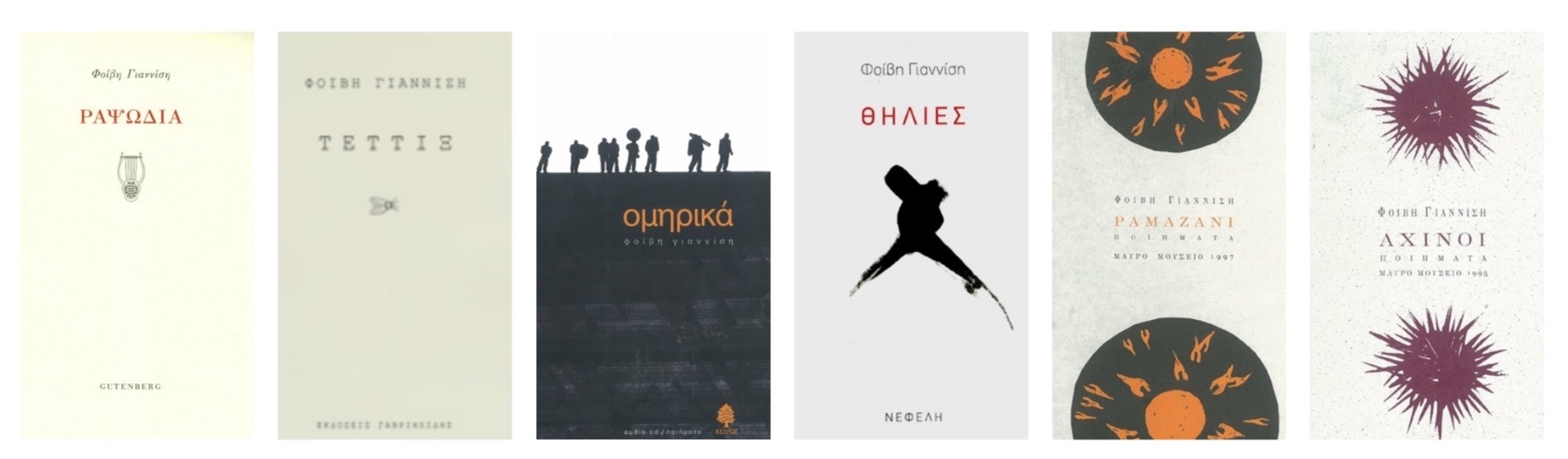

From Sea Urchins in 1995 to Rhapsody in 2016. Have there been any recurrent points of reference in your poetry? And, in turn, how has your poetry evolved over the years?

When I, or everybody, do attempt a flashback at my life or my work, I am conscious as everyone that such recast is different depending on the moment it takes place; for this reason it is false and true at the same time. So I can only say that I came up today (July-September 2017) with the following landmarks:

As a child I was an ardent reader of prose and mythology. But then, in my teenage years – my years of ephebeia – Elytis woke me up poetically arousing a physical excitement, and causing the experience of a kind of loss in poetic intoxication (to use Baudelaire’s words: “il faut toujours être ivre”). Nowadays many Greek poets despise Elytis exactly for the laudatory construction of Greece that is attributed to him, but the creative misinterpretation of the father, is a prerequisite for “ephebe” poets, if we take Harold Bloom’s theory. So I do not deny my initial love for him, given that the excitement and transformation in the teenage/erotic body during the summer has since become for me the emblematic condition of the poetic moment, the moment that throws straight into poetry. Elytis then has been interrelated with modern Greek prose writers along with Ritsos, Arthur Rimbaud, and Federico Garcia Lorca; that was a lyrical-epic era.

Later, and under the influence of E.X. Gonatas, that I was visiting in his small house in Kifissia, as Eva Stefani has filmed in her Episkepseis, I turned to poetic prose in small form, published in the literary journal Black Museum (issued by a group of friends, university students, during the 1980s). I started writing poetry anew early in the 1990s and published Sea Urchins (Black Museum, 1995) and Ramazan (Black Museum, 1997), echoing surrealism as imprinted in Greek poetry, mainly Engonopoulos, Empeirikos but also Andre Breton, as well as Andre Pieyre de Mandiargues, with a flood of natural images and industrial ruins. Poetry was coming as a flow, and I think I owe much to the recordings of Embeirikos and Engonopoulos reading their own poetry that I was listening.

There followed Loops (Nefeli, 2005), written from 1999 onwards, with the consolidation of the erotic element, leading to other paths still attached to Andreas Embeirikos and Matsi Hatzilazarou which is a tremendous erotic female poet, and Miltos Sachtouris, whom I met at his late years, visiting him every week at his small house in Kypseli.

Since the early 1990s I have also been an ardent reader of Marina Tsvetaeva, which I literally love in her entirety; I cherish for Marina a kind of worship such as the one that is attributed to heroes, to rock stars. I buy her books in all the languages I can understand, and suck them. Tsvetaeva is a phenomenon that affects me always, the same way love and motherhood does, pulling me up and helping me realize and accept my feminine side as a kind of power.

In Homerica (Kedros, 2009, German Edition translated by Dirk Uwe Hansen), I started more consciously working on my poetics, using the first person of the poem as a mask, in order to multiply the voices, by inserting mythical figures of the Greek antiquity, while also elaborating the syntax along the lines. However, I mostly focused on rhythm, creating small waterfalls, since my poetry was mainly heading towards vocalization; poems were written in one breath and took their final form through resounding repetition. I read again Homer, Iliad, which opened up to me as a revelation after years of tackling with Odyssey, Ancient Greek Lyric poets such as Ibycus or Alcman or Anacreon, Pound, Eliot, Rilke, Hölderlin, Derek Walcott. My familiarization with the work of the major contemporary German poet Barbara Kohler opened me to understand modern poetry as a field of constant artistic research. At that time, the revelation of how important voice and sound are, reshaped therefore my personal poetics and led me to insert in the book a CD, The CD was composed by the series of in situ recitations made in a two-day solitary wandering in Pelion’s mythical places related to the poems content: I wanted to add to my verses the specific moments’ atmosphere transferred by its sound. That was my way to include the poetic haecceity, the perfect individuality of the moment as sensed through the place, to re-interpret the term introduced in Mille Plateaux by Deleuze-Guattari.

At that point, focusing on animated place, I turned to research on the poet/singer’s animal aspect, as we read it in ancient Greek poetry: cicadas, goats, birds, the nightingale are archetypal figures for poets. This turn led me to create poetic works researching in other fields such as philosophy, biology, ecology or ethnography and using multiple media.

For Tettix (Gavriilidis, 2012) I exhaustively read Plato’s Phaedrus, Archilochus, Hesiod, Sappho, Ann Carson, Jesper Svenbro, Bakhtin on polyphony and Mille plateaux by Deleuze and Gauttari. I was thinking that the cicada’s metamorphosis /ekdysis of its shed is an emblematic image for the multiplicity of a poet that starts singing. I tried to transform poetry first into an installation (Tettix, National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012, curated by Stamatis Schizakis), and after into a book. I have then delved into the subjects of polyphony and reading, body and writing, along with lust, summer and the sound dimension of space. Τhe crafted element of handwritten composition was inserted to the project, and the book identity became hybrid with the inclusion, translation and editing of texts of other writers as well. For the installation I created a video poem and audio that took the form of sound “paths” with mixing of recordings, recitations and music. In Tettix, I tried to experiment with polyphony not only by the form of the installation, but also by the creation of a performance with several readers together trying to mimic the polyphonic sound of cicadas inside the landscape.

For my last published work, Rhapsody (Gutenberg, 2016) I returned to the simplest form of the book, binding different and various in form and content poetic projects together. I include miniscule poems, prose poems, songs, philosophical thinking, and a new genre I named “bodily philology” i.e. a poem/essay that can be performed as a lecture, commenting on other poems.

Within this flow, my latest project (Chimera, under publication) became even more complicate, more chimerically diverse, since for its elaboration I tried to come closer to the goat, the female, the mother, the sacrificed Other, the animal, the nomad, the continuously moving or the marginalized being, the one that lives “outside” a given community, and speak in sympathy with their unheard voice. For this project I followed a group of Vlach shepherds, that are still practicing transhumance with their goats, from Thessaly to Pindos Mountain, and I am deeply grateful to them for letting me in. This archaic kind of stock raising with its violent but also symbiotic part made me better understand life’s complicate aspects.

Chimera was thus a multilayered research on the poet’s identities, shifting between the bucolic, the tragic and the comic as genres. Inside the project we hear bucolic poets, travelers, ethnographs, folk songs, goats and shepherds talking to their animals, along with Papadiamantis, Krystallis, Christovassilis or Derrida. This project took also the form of an installation (AIGAI-Ω, together with Iris Lycourioti), with its video and audio sections. I also created AIGIS, another reading device, a map-dress made from handwritten goat skin. Chimera/Aigai-Ω has also served as a basis for several performances, each of them different from the other.

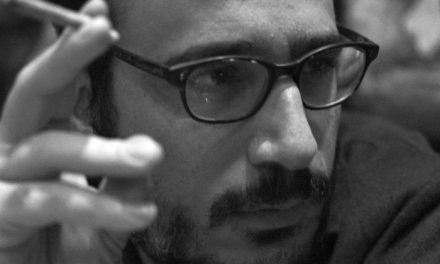

@Beowulf Sheehan

@Beowulf Sheehan

Brian Sneeden describes translating your poems as “a transformative experience,” noting that they “require a certain capacity for surrender – both in terms of how one experiences language and its perceived boundaries, but also in regards to the boundaries of English, which does not draw quite as easily as Greek from a vocabulary steeped in so ancient a history”. How would you comment on that?

If I understand well the question, Brian, who just finished the translation of Homerica (to be published in the USA in October) refers to the untranslatable, in a level that concerns the relationship of the Greek word to the depth of history.

The truth is that for me making poetry means admiring language; being moved by, meditating on, listening to, searching through language. Above all it is a very attentive effort to hear, being an eavesdropper and a thief, like the god Hermes. I am looking for the poem of the living oral word articulated by people who still know how to make it vibrate. And I try to remember it – but I always forget it. I gather the words like fruits and I devour them. I contemplate the word. I research its etymology. I search for the meanings in the dictionary, and I read the ancient quotes that have been found and contain it. The fragments of texts circle me. I try to rip the language of others, like a cicada that extracts the juice of a tree with its sucker, which is both an embolus and a tongue, and metabolizes it through the erotic desire into a song created by its own musical instrument. I guess the same goes for all languages; yet this is my own shore. I cannot really feel any other language even if I understand them, since I am born inside that specific one, and I am lucky since it draws from the Homeric and the Sapphic. My place is my language, and my language is my place.

However, when I write, my words are simple, far from being pretentiously poetic. Just the opposite; I believe that an intentionally poetic language that uses of specific words is fake and empty. It pretends to be poetry but it is not; and unfortunately in Greece this pretentiousness is traditionally identified with ‘Poetry’, with a capital P.

Instead, if language is poetry, then the unattainable limit would be the almost incomprehensible that can move the recipient, and here I quote Alkman that claimed: “οἶδα δ ̓ ὀρνίχων νόμως πάντων.” Which means, “I know all the songs/melodies of birds,” the songs of the greatest singers, those who live in the sky, between us and the gods, who are radically different from me and whose language I do not understand (or do I actually understand? Alkman does not make it clear), “the singers up there” who belong to a different species; yet given that they are the prototype singers, they can sing better than me, our difference may not be radical and maybe then no difference is radical. Poetry is a becoming. If one pushes the reasoning to the extreme, then the poem is only a song, a music, that you experience or feel through its charm even if you don’t understand it. This is of course an impossible work. But as the proverb says, “walker, there is no road, the road is made by walking”. We walk our language wherever it may take us.

Your work lies at the border between poetry, performance, theory, and installation, investigating the connections between language, voice, body, place and memory. What is the binding thread?

I cannot answer this question the same way as one of my readers. So I will speak in terms of my poetics, which I have been exploring theoretically, and which feed my practice. A crucial question posed in poetry as far as I am concerned, is, in Socrates’ words, to know oneself, the poetic self, that speaking voice in a poem, to which Socrates in Plato’s Phaedrus answers offering two alternatives: I am either a simple being or a complex one, as Typhon or Chimera. Rather than answer with the identity of the one, I answer, as I cannot do otherwise, with the identity of the multiplicity, the Chimera. As it turns out, the complex being constitutes my poetics, a multiple body composed of various “μέλη”, parts, songs, kinds and media.

The living body is definitely in the center of this activity: poetry is but a response to stimuli which touch, permeate and agitate the body. I am referring to the simplest stimuli, the contact with other beings, with the earth and the place, with the everyday, with life, with memory, with others’ poetry, with what comes from the outside, triggering emotion. Inspiration is a kind of inhalation of the other, that is returned to the outside by a construction made with feeling and thinking. Every part and every species that compose the Chimera has its own autonomy, yet all function evenly as a network.

As I grow up, I have come to realize that for me poetry, writing and vocalization constitute also a form of therapy. As Eleni Stecopoulos aptly puts it in her book Visceral Poetics, poetry is a kind of healing practice, it has to do with illness, it is visceral, sympathetic, it is a form of care in order to be. For me, the practice of handwriting as well as writing itself is such an activity, just like oral recitation is a ritual of healing. More and more consciously, as I practice poetry, I invent a ritual that makes me forget. The cicada that metabolizes the juice is such a vain momentary effort that heals pain without curing.

“The dense minimal poems of Giannisi explore with arresting directness the relationship between language and the elements of the natural world with a language which is always subtle and inornate, skillfully bare,” as Haris Vlavianos aptly put it. What is the relationship between art and the urban landscape? Where does poetry meet the natural world in your writings?

Already from my early writings, one could easily discern a quest to utter the experience of a relationship, either enthusiastic or mournful, to the natural element. Is it a kind of return to the archaic? Is this a kind of celebration to beauty? Or is it rather a kind of grief, a desperate attempt to bring the being out of oblivion?

This “archaism” should not be dissociated from language and representation. The so-called ‘natural’ world (along with the questions this term poses in the 21st century in relation to the construction of the natural as part of the cultural) is my window to poetry. But the bodily senses are mediated by their expressiveness through constructed language, which means poetry or philosophy, the first ax that dug this world.

@Tassos Vrettos

@Tassos Vrettos

Svenbro writes about the first samples of writings, the inscriptions put in verse on ancient Greek statues, where the first person was used to refer to the object bearing the inscription: “Mr. Brugmann accepts the hypothesis that the Greek ‘ego’ is descended from an Indo-European noun, eg(h)om, meaning Hierheit, “hereness”.” (p. 73, Phrasikleia). I consider this etymology of the ‘I”, “ego”, as related to locality, to “hereness”, a very appealing interpretation, so suitable that it looks fake, for my work. If the “I” is nothing less than a ‘here’, then the voice in poetry expresses nothing but this ‘here’, yet through the multiplicity of subjects, those Others, that dwell ‘here’ at that very moment. Place and language together, language as a place.

If science answers a question that has been formulated, then art responds to questions that never arose, to a kind of a call. In poetry, this is the call of the Other. In the urban landscape, the Other, different but also similar, is related to the human and the social. The urban space renders the human multiplicity; an immense and living complex environment, with its own built typology, its patterns of repetition and ritual, its singular events. Urban space offers the vital perspective of meeting different subjectivities, carrying a polyphony of their own myths and voices.. That’s why situationalists reflect on the city as the primary place for the theater of life, where everyone can playfully participate. City wandering and oral dealings with people enrich experience in the most surprising and joyful way; they also reveal human pain, social inequalities and struggles. Last but not least, the urban space is also the area of publication, where the poet returns to the public what may have been created somewhere in the loneliness, outside.

How would you comment on current literary and artistic production in Greece? Could art offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Nowadays art in Greece witnesses the advent of many significant and positive elements; first and foremost, the introduction of practices and activities which move beyond the scope of consumption, outside the usual institutions (museums or galleries), not losing nevertheless their visibility to the audience; and second, these practices are in direct communication and contact with international currents and tactics. Some of them are in a way mimetic. Others take place through the creation and implementation of platforms or groups that intensify the sense of belonging and through the existence of networks they help the development of new kind of symbioses. We all experience the emergence of social and earth issues following the onset of neoliberalism and frantic capitalism, often vis-à-vis vulnerable social groups, natural resources and groups of animal populations. A new form of art is thus happening, claiming the “commons” in general, against discriminations, and connected to practices of care for the other and for the weak whether it is human or nonhuman. I believe that all the aforementioned changes are for sure a reaction to a totally scaring social and environmental reality for the entire world, ruled only by the economy of profit. And these emerging art practices constitute a remarkable victory on the part of social imaginary.

At the same time, due to the spread of new media, questions arouse again about the role of art, about the medium itself, about art actors, about the importance of representation, production and reproduction. Fields and their respective boundary limits seem to be confused, as we definitely face a significant turn into the unknown, just like a wave amid the turbulence of winds blowing from all directions in the ocean, to use Homer’s words to describe Nestor’s turmoil.

Recently, we experience in Greece a kind of productive explosion, both cultural but also poetic. I will leave aside Documenta that has just closed its doors, a lot has already been said on the issue. But in case somebody follows social networks alone, here, he will be sure to witness a major boom: exhibitions, readings, editions, actions, festivities, most of them in public spaces. Yet, is this boom for real? It’s difficult to discern between what is real and what is media made, because the internet is a scene where we are all showing our narcissistic aspects and alternate as stars. In a way we haven’t been used to until now and for which the oldest ones as me feel a little intimidated, yet remain unable to abstain from using, we are shifting in between the roles of the actor and the commentator, the viewer, in order to become visible on the net. For many contemporary thinkers virtual reality of course has actually become THE reality, and one can no longer differentiate. But while the web universe constitutes a powerful and active part of our daily life, as well as an integral part of the public space, it co-exists with the other reality, that of being inside our bodies and the physical space of their co-existence.

As for poetry, In Greece, a lack of the bodily dimension has been the fact for several years, since it has been abolished from the lyrical/heroic era of Hadjidakis and Theodorakis,). This lack created a reaction, the urgent need to get the poetic speech out of the closet so that it is loudly articulated among people that are physically present. Amid the welter of the potential, arises the opposite need: to meet in person, to see, touch and hear each other, so that the speech, our thoughts and feelings are also physically dispensed and shared. Early in 2000 in Bar Dasein, the poetry now group, which was later transformed in [frmk], fervently initiated the institution of public poetry readings and discussions. I personally began to associate myself with the urban space presence, public practices and the questions they raised, during the 1990s and through my participation in the Urban Void collective of architects and artists; yet, the public poetry readings of 2000 enhanced the personal meetings in between poets themselves and their public. Although not so far back, such readings were then shocking the poetic status quo and received no publicity whatsoever from institutional critics. Nevertheless the initiative of these collective public readings that started at the period, led also to the creation of groups and collectivities, that also publish in their own magazines, and this changed the public image of poetry in Greece.

Younger poets, who came to the forefront after 2010, are very glad to discover this dimension, which arose directly from the previous enclosed use of poetry, and I think this is actually quite promising. We should of course realize that what is unfolding in Greece now or a from a decade ago, with a newcomer’s enthusiasm, constitutes common ground because it has been taking place for many years elsewhere, so that what is important is not just the fact that it is happening but how it is happening. In the US, for instance, there is a long and very sophisticated tradition. Last year I followed in New York some poetic events that amazed me such as, for example, a performance by Julie Ezelle Patton, that improvised on two poems combining voice, dialogic reading and jazz music; a breathtaking experience. I also attended poetry readings and discussions in bookstores of a very high quality and with a very strong participation from the audience that we couldn’t imagine here in Greece, for the moment at least. We should thus continue on this way of public space performative readings and discussions, by elaborating on the obvious as much as we can. To use Heraclitus’ words, this kykeon may exist as such as long as it remains restless. So let’s contribute to this end and blend and mix its ingredients by our constant contribution in order to savor it.

In recent years the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry has been rekindled, with an increasing number of Greek anthologies being translated in English. What is it that makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

Nowadays the interest in Greek poetry abroad has been renewed, and anthologies have crucially contributed to this end. It’s something that Greek poetry certainly needs, given that it is written in a language unfortunately read by very few on a global level, which, however constitutes its measure. Translations communicate the work to other languages and readers. In this framework, the anthologies that have been published play an important part in further publicizing the translation and spread of new Greek poetry, which has always tried to be kept updated, to be in touch with international trends, ever since the era of Papadiamantis.

Τoday, the internet allows for and incredibly facilitates the diffusion of the contemporary production in poetry; it’s much easier than in the past to single out poets in larger numbers and from a variety of origins. Often too much information is drowning our creativity, but, except that, nowadays there is this great chance, the chance for a poem to be re-transformed through new hands, through other people, through a different language. I personally feel extremely grateful to this incredibly generous stranger, the translator, who hosts me in his/her language and distributes my work anew to his/her audience. So Ι take here the opportunity to thank all my translators in other languages, and mostly Dirk Uwe Hansen who translated and published Homerika in German (Homerika, Reinecke & Voßm 2016), Brian Sneeden, who continues now in English, and all the editors of poetry anthologies, such as Karen Van Dyck, Thodoris Chiotis, and all other “ambassadors” (πρόξενοι, a beautiful word in Greek).

The above said I’m still afraid that the interest in Greek poetry may be exhausted on the basis of mere thematics, so that it can meet the criteria of broader consumption and easier readership. In other words, there is the risk of a new marginalization, an exoticism, through a logic of the type: “let’s see what those indigenous Greeks are doing now amid the crisis”. And this puts Greek poetry in the position of having to respond, just to fit the preconceptions regarding the specific question, respond to the bulimic and neocolonial request to represent through its poetic voice those others facing a social problem, but which is at the same time global. Have we become poets due to the crisis, and just for the crisis?

But to use Marina Tsvetaeva’s words, the relation of a poet with time is far from linear. Poets, she writes, are always inside time by no following it. There are poets that live AFTER their time, and others who live BEFORE, who transfer a thing or a way of the future or the past to their poetic present, not just in terms of thematics but of language as well. Τhe quest for the ephemeral, for the easily consumable, for what lives entirely WITHIN its time, resembles some newspaper readers, Tsvetaeva says, and has nothing to do with poetry and its aims.

I firmly believe that poetry is a field of freedom that constantly redraws itself and its boundaries. Poetry is not just a subject but a way, poetry is a becoming. Since an early age, I revolted against that unique poetic meaning that we had to learn and to search for in the texts of literature at school. My insistence on the plurality of meanings, my understanding of poetry as a becoming, has always been my motivation for new readings; the same goes for my writing. Yes, poetry can be a revolutionary therapy since it is written with no usable value whatsoever.

* Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE