Stavroula Papadaki was born in 1991 in Athens. She studied philology at the University of Athens, delved into Greek and European poetry at the Takis Sinopoulos Foundation and created the online literary and artistic magazine LYKOS. She works as an art director in the field of communication and branding and as a scriptwriter in the cinema. Her writings have been published in print and online magazines. Her first book of poems And what people would say? (Kappa Publishing, 2023) was shortlisted for the Newcomer in Poetry Award 2024 by ‘Anagnostis’ literary magazine.

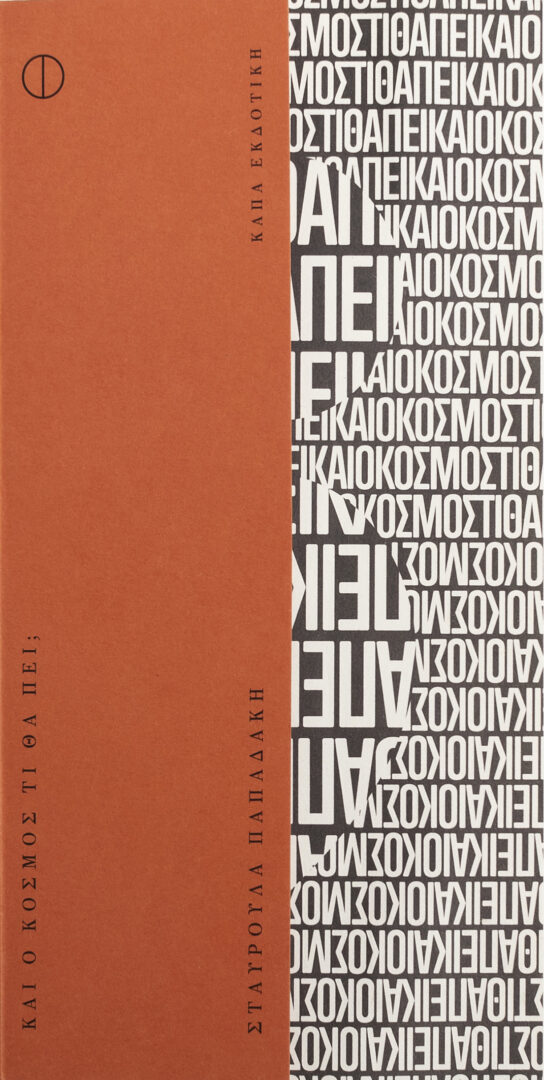

Your first writing venture Και ο κόσμος τι θα πει; [And what people would say?] was recently published by Kappa Publishing. Tell us a few things about the book and its title.

For me, writing is both a necessity and a form of freedom. It is a place where many things can happen, where I am allowed to be myself, a hideaway to escape to whenever life becomes tough. For a long time, I felt that consciously pursuing the publication of a book would be a tremendous psychological risk. It would be a significant risk to expose my hideout, to hear that this place is not as fantastic as I had imagined it, to show people a side of me that is wrinkled and unseen – especially since, to many, I was and still am “the good kid and the good student,” something that has preoccupied and trapped me, and which I am in the process of changing.

The title And what will people say? made this process more bearable for me. Somehow, I decided that this first attempt at exposure would also be an exercise in freedom. The title is a challenge/invitation for everyone to say whatever they want – a form of protection, as if I have accepted that people might eventually talk about it, and it’s no big deal, and a curiosity to hear things that might help me take a step further.

Along the way, I realized that my need for freedom resonated with many others, especially in today’s world, where everything seems accessible and free, but in reality, it isn’t.

Τhe book constitutes “an attempt to capture that ideal condition in which we are allowed to live in our world while maintaining a view of the world of others and to record the very moment of this process of personal and gender emancipation”. Could poetry be used to talk both about our personal demons as well as broader social issues such as gender, solidarity and emancipation?

Definitely so. Poetry and, generally, the literature that moves me starts from lived experiences, from the microscopic, the everyday, the suffocating, and become windows through which we can see outside, see others, the sky, the horizon, and take a breath of fresh air. Since I experiment with both poetry and short stories, I feel that poetry is more cryptic and thus allows greater freedom to address topics that you might feel uncomfortable approaching otherwise. This discomfort comes naturally due to many things: from the way one has been raised, from the often entrenched notions of good and evil, from the concealed guilt of “there’s no such thing as can’t, there’s only don’t want to,” and from political correctness, which often loses its essence and purpose. My belief that poetry is more cryptic doesn’t mean, of course, that it is not also revealing.

As one of my favorite poets, Jenny Mastoraki, said in an interview, and I often bring it to mind: “A poem has the basic property of fluids: it takes the shape of the container that holds it. That container being the reader. When this happens—and I say ‘when’ because it is rare—then, yes, the poem becomes like a magic mirror, reflecting something different each time. The most important thing is that it reflects something other than what the poet had in mind.”

So, yes, magic happens when a personal demon, through poetry, becomes a genie for someone else. When, through poetry, someone finds words to describe their trauma, and somehow, for a moment, this understanding seems to have a healing power. For me, many poets have described what I was experiencing at a certain time (even though they might have been talking about something entirely different), and I feel they have helped me heal. I owe them, in other words.

Μore generally, how does literature converse with the world it inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

For me, literature converses with the world by acting as a mirror. It reflects social, political and cultural conditions, providing insight into the human condition, societal norms, and collective traumas. Through satire, allegory, symbolism, and narrative, writers attempt to make sense of the strange occurrences in the world and seek a way to exist within it. This observation, the focus on things, the questions that arise create a sense of security, that some will be aware of, others will find a way to speak out, highlight social injustices, and cultivate empathy and understanding for the different, the opposite, the other.

I have often pondered what a poem can achieve for peace while a war rages on. This is why I sometimes avoid themes where my imagination might fall short of. However, I have concluded that this act of observation, the conscious decision to pause life for a moment and write about something, is a significant political act in an era of speed and intimidation. Acts of kindness and courtesy are equally important.

Regarding whether literature empowers us to imagine different realities, my answer is a definite yes. Although I am not a fan of science fiction per se, I am a fan of imagination and exaggeration because they create worlds that challenge our notions of what is possible. Utopian and dystopian narratives have always envisioned ideal or nightmarish futures based on current conditions, serving both as warnings and inspirations for change, both personal and collective. Examples like George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale confirm that literature can critique wrongs, suggest alternative ways of living, and open new horizons of expectation.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is many things. It encompasses words but also includes a black straight line, a touch, a glance, a few notes. The language I happen to speak best is words, so I’ll say that words are the tool I have as an adult and the play that reminds me that I am also a child. It is my way of shaping ideas and emotions, capturing images and people, focusing, and attempting to connect with others.

Although, as Toni Morrison said, and I agree, “Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names,” I love and simultaneously fear the language of words. Unlike, for example, the language of music, which often allows for more ambiguity, the language of words forces us to be precise and specific. It reveals our origins and history, our beliefs before they are fully formed, and leaves room for misunderstanding. It also restores clarity, but first, it allows for confusion.

On the other hand, as I mentioned, I try not to worry about this, and to overcome obstacles and boundaries. After all, everything would be quite dull if we all agreed on concepts, had a common language, and didn’t insist on creating our own languages and codes with those who matter to us.

In my writings, I aim to use simple, contemporary language and experiment with the ways I can use it. I used to worry about literary quality and believed that a text needed “serious,” “scholarly,” and “sophisticated” words to be considered “serious,” mainly because this is a common belief in the field. However, I no longer believe this and do not care at all. What interests me now is the style, the immediacy, the vibrancy, and the orality.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

The challenges faced by new writers today are undoubtedly numerous and multi-faceted. I often remind myself that we are in a relatively underdeveloped country, and what new writers face is just an aspect of the broader difficulties they encounter as individuals. It is well-known that most publishers ask for money to publish a debut book, seeking to mitigate the risk of publishing an unknown author. I understand this to an extent.

However, this situation raises several questions: a) What value is returned to new writers who can afford to pay this cost? Does it include thorough editing, a strategic marketing plan, and a modern presentation appropriate for their age? b) If there is no risk for publishers, how can there be a conscious risk in choosing and supporting a book? c) What happens to those who write but cannot even explore the possibility of publishing their book due to actual financial difficulties?

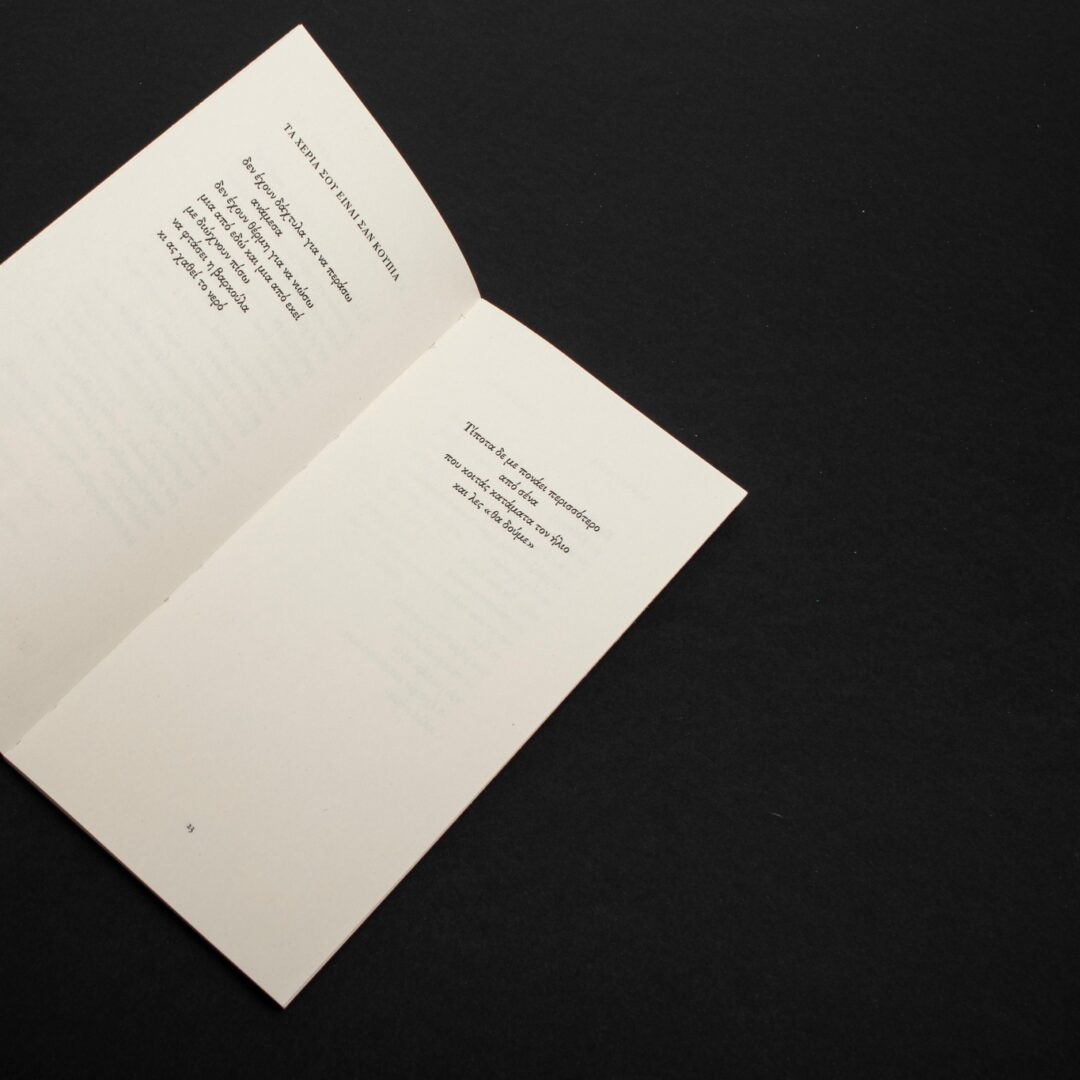

I do not know the answers. I know these questions have been on my mind a lot; I delayed publishing my book for a long time because I feared being asked for money that I could not (and would not want to) give. However, I was fortunate to approach Kappa Publishing at a time when they were interested in investing in and supporting new writers through their poetry series, Flexi. Believing in my book and in me, they did not require payment for its publication and took care of it as much as they could, for which I am grateful.

Social media has helped bring my writings closer to people—which is my primary goal. It has connected me directly with admired authors, provided valuable feedback (both positive and negative), and allowed me to express myself openly from a younger age, contributing to the development of a measured self-confidence, as some people resonate with what I share. Therefore, I believe social media plays a crucial role in promoting new literary voices and creating a supportive community of emerging writers.

How do young writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local meet the national and the universal?

I think the first thing that comes to mind is the internet. The internet has provided access to information, erased distances, and enabled direct communication with writers we admire on the other side of the world. Social media allows new writers to track trends, experiment with different styles and mediums, and share their work—all at no cost and without having to wait for the long-desired publication. In fact, abroad, many authors often build their audience before their first book is officially published.

The intersection of local, national, and universal elements in the work of new writers often emerges through the blending of personal and cultural narratives with broader, universal themes. New writers draw inspiration from their surroundings and daily life, infusing their stories with unique cultural elements, dialects, and experiences. At the same time, they address global issues such as love, death, identity, social justice, and freedom—topics that concern us to varying degrees across time and resonate with a wide audience worldwide.

In Greece, this connection to the global literary scene is more challenging due to language barriers. Writing in English opens different opportunities compared to writing in Greek. This obstacle could be overcome with appropriate outreach and translation programs for books, official training on festivals and the functioning of the system, transparent intercultural exchanges, participation in international literary festivals, and substantial support for notable domestic literary initiatives. These measures could make Greek literature a magnet for international engagement and exchange of ideas with foreign writers. Currently, this interaction between local, national, and global is somewhat lacking, but as we said before, we are a developing country taking steps forward, so there is still a way to go.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE