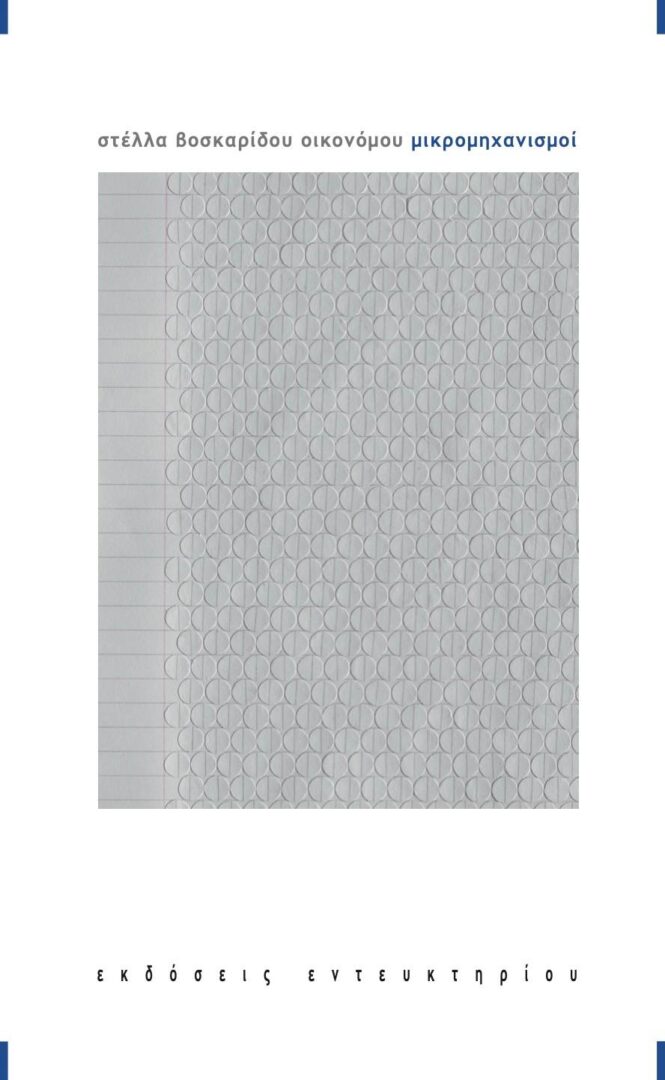

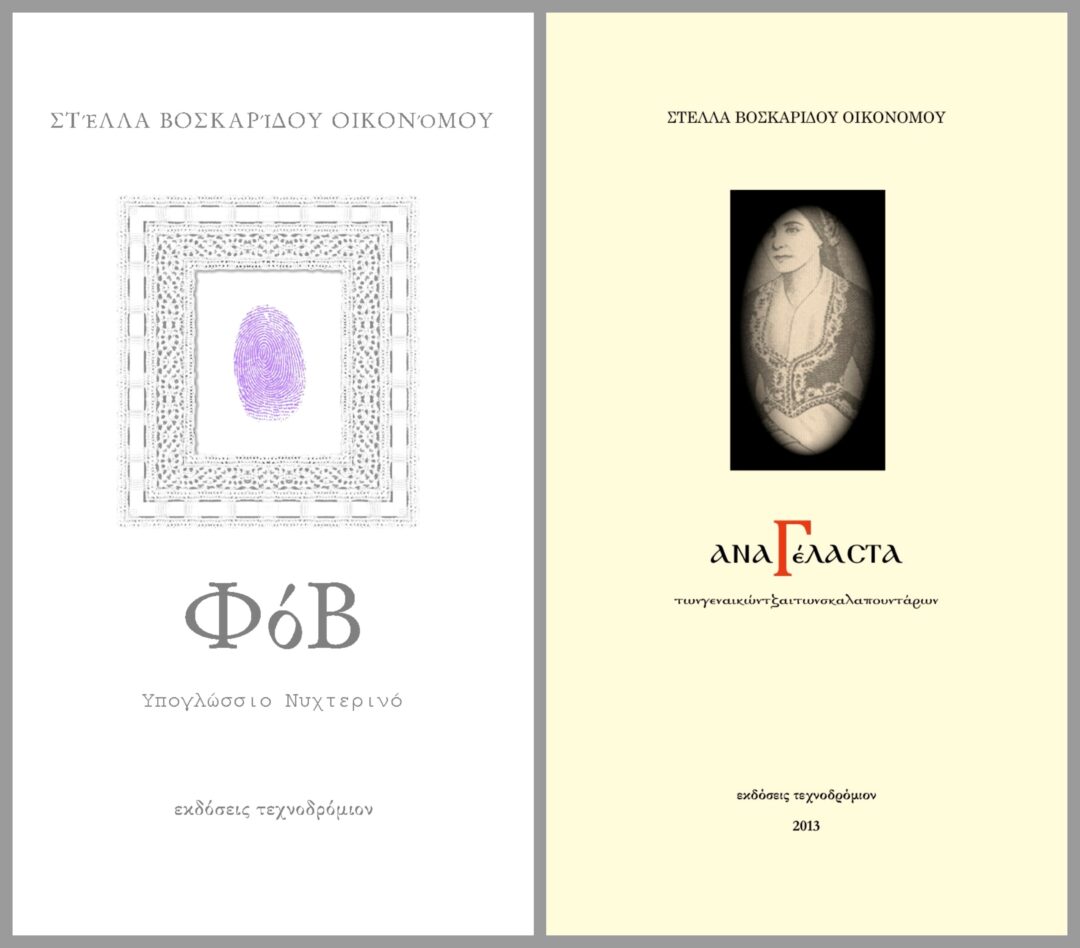

Stella Voskaridou Ekonomou (Limassol, 1981) studied Musicology in Athens and the UK. She has published the poetry collections Laughlessly (2013) and Scurple, sublingual nocturnal (2015) both published by Tehcnodromion Publications, as well as Micromechanisms (Entefktirio Publications, 2022). In 2017 she was the winner of the 1st International Poetry Slam held in Cyprus. Her works have been featured in numerous print and online magazines, anthologies, and presented in various international festivals (Cyprus, Thessaloniki, Belgrade, London, Shanghai). Her writings have been translated into Serbian, English, Chinese and Spanish.

Sounds, images, words are interweaved in your latest writing venture Micromechanisms. Tell us a few things about the book and the main themes it delves into.

I have no memories of myself starting to write something with a specific theme in mind. Most of the times, I start from a need to trace or question my very voice or from a sense that I have to part my voice from some noise, to regain the signal. Only afterwards am I able to trace the theme, which is always interwoven with the ontological need for writing. In this procedure, I am inevitably confronted with the complexity of language. I have to approach language in its most material form, and be ready to handle all of its functions. Sounds, images, music, syntax and grammar, fragments and narration are all in the game for this reason. In my latest book Micromechanisms I ended up with a text centred around the (im)possibility of language (or, in other words, dead ends and miracles) as well as the relationship between the parts and the whole. The latter was of course no less fruitful for its ability to work as an allegory for the very existence, which is nothing else than the agony to understand eternity while inhabiting a body with an expiration date.

Since your first poetry collection Laughlessly till Micromechanisms almost ten years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your poetry? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

All of the issues I mentioned above are in several ways present in my works, although they leave a different imprint in each book. Laughlessly is a book written exclusively in the Cypriot dialect. This choice set some very special terms regarding the formulation of the text. I needed to develop a very sensitive reflex to regulate the balance between the oral and the written version of language, but also between the literary and the traditional aspects of it. It felt as if I needed to domesticate a monster, while bringing the dialect towards surrealism and the absurd (and I’m still not able to trace which one is the monster and which one is the domest). The more I think about it, the more I realise that I was closer to martial arts than to literature while writing Laughlessly.

The big difference between that book and my later works is that I had the need and the chance for much more conscious reading in the years that followed the publication of Laughlessly. Additionally to my initial personal need for curing my voice, all this reading left me with a deep desire to release my voice in every possible way. Thus, the writing experience has always been exciting for me, even when it came with the darkest colours.

What about language? What role does language play in your poetry?

I am helplessly devoted to language. The more I am into poetry, the more I realise that poetry cannot be anything other than language. Look at language: at its one end there is the nonsense and at the other there is the God. George Steiner says that language adjoins light, music and silence; it sounds as an irresistible playground to me. An irresistible playground to rejoin oneself. To make it a bit more earthly. It was after studying semiology that I got a great poetic shock; when I realised that we are surrounded by millions of languages that penetrate each other. And these languages are soft like dough and like clay, and sometimes they become liquid, and you always need to strive in order to keep them upright, and you have to struggle and you have to work hard if you want to be able to sing a song and touch one’s heart and prevent words from melting in your mouth.

Where does poetry meet music in your work? Would you say that they constitute communicating vessels?

As Julia Kristeva suggests, music is the semiological system of infinite meanings. In this sense, the meeting point between language and music is definitely polysemy; the shift from the tyranny of the monolithic, to the dew of the compound, kaleidoscopic answers. The road towards spaciousness and plasticity (for some reason the term plasticity always drives me towards kindness). From the same perspective, one could also suggest that the meeting point between music and language is a more democratic place. It is a communicational precondition which gives the readers plenty of space for thought and reflection. For Schopenhauer, on the other hand, music is an art that reflects the will and the soul in the most unmediated way. I come back to Kristeva and Schopenhauer’s views very often, because in both of them, music and, by extension, poetry which constitutes an inclination of language towards music, appear to be deeply connected to freedom and innocence. To my eyes, this is an invaluable antidote to the speech of authority, to propaganda and to the rhetoric that aims to human manipulation. It is regaining of our deserved space.

How does poetry converse with the surrounding environment? Could poetry be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

When exploring the edges of language, one does nothing else but approach the limits of social reality. It might sound too theoretical but it’s not: language in poetry tests our reflexes in multiple ways. It asks us how easily we can move from high art to everyday speech and if we are addicted to authority and the laws of rhetoric; if we afford the uncertainty of metaphors and if we are ready to question stereotypes. It calls for adventure. It calls for trust and for faith sometimes. In all of these cases both the writers and the readers go through a very powerful journey of self-consciousness. Even if one does not realise it, poetry transforms its readers, and this transformation is one of multiple levels. The boost of imagination is of course an important part of it and this has a crucial political effect: Social change starts from the moment at which one can imagine that things can happen in a different manner than the one in which they already do.

How do young writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/national meets the global and the universal?

Reading is the most important answer to this question. Every writer is also a reader and these two qualities function as communicating vessels. The voice of every writer is that sea into which many rivers flow. Of course, the soil morphology, the chlora, as well as other characteristics of the local environment determine the types of fish that the sea offers. The local and the universal finally meet at the centre of every human being’s soul; where the most archetypical agonies lie. The agonies that go beyond the historical circumstances and carry the very needs and desires of every individual. Or the needs, the worries and the desires that determine all historical circumstances after all. They are very few; countable on one hand’s fingers: love, death and the yearning for power over each other, unfortunately.

The 21st century came with a great gift; unprecedented accessibility to world’s literatures. The internet, social media and mobility that helps writers to meet each other’s work are factors that help towards this direction. However, the most significant part of this procedure is when the writer gets an adequate distance from his or her own route and allows his or her self to see it as part of a bigger map, including all the routes, and all the nations and all the wars and the revolutions, and all the wild kisses that kept the warriors alive; the planets and the stars that send their little light to our bedrooms every night. It is the moment at which an experience finds its true value and meaning and becomes great poetry.

*Ιnterview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE