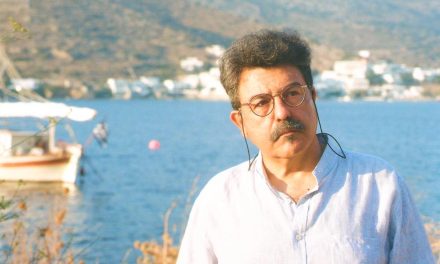

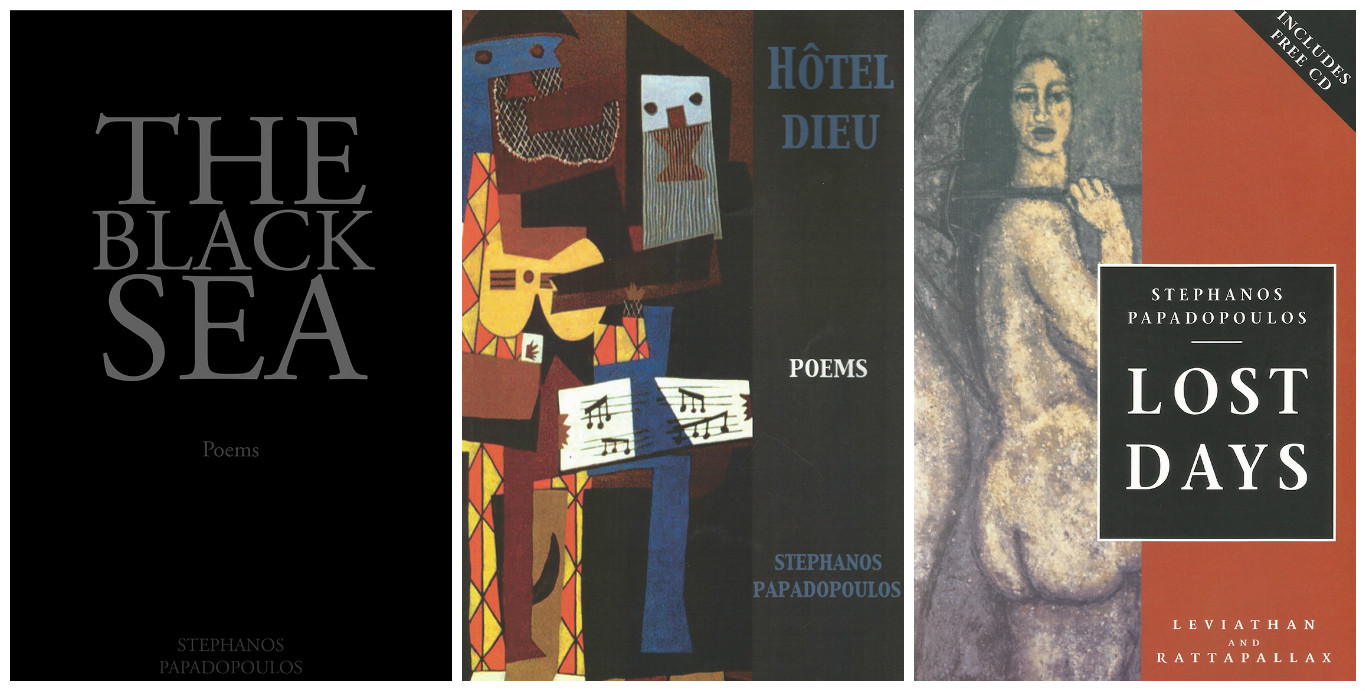

Stephanos Papadopoulos was born in North Carolina in 1976 and raised in Paris and Athens. He is the author of three books of poems : Lost Days, Hôtel-Dieu, and The Black Sea, as well as the editor and co-translator (with Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke) of Derek Walcott’s Selected Poems into Greek (Kastaniotis Editions, 2006). He was awarded a Civitella Ranieri Fellowship for The Black Sea and in 2014 he was awarded the Jeannette Haien Ballard Writer’s Prize selected by Mark Strand.

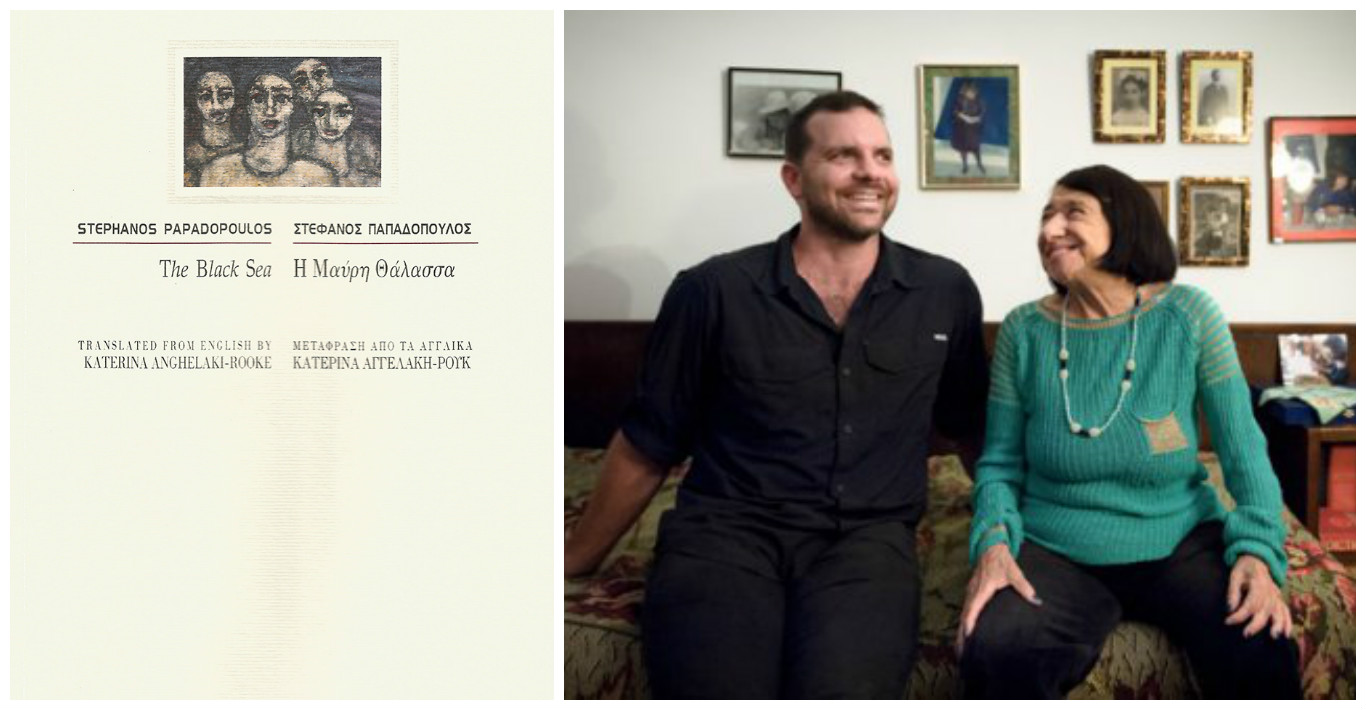

His poems and translations have appeared in journals such as The New Republic, The Yale Review, Poetry Review, Stand Magazine and he writes regularly for the Los Angeles Review of Books. He has translated works of Greek poets, Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, Yiannis Ritsos and Kostas Karyotakis among others. His own work had been translated into Greek by Katerina Anghelaki–Rooke, Italian by Matteo Campagnoli and Spanish by Rodrigo Rojas.

Stephanos Papadopoulos spoke to Reading Greece* about his most recent collection The Black Sea, a long poem-cycle exploring the histroric “great catastrophe” of the Pontic Greeks of Asia Minor in the 1920s, “the human condition” as the inspiration behind his poems, how cosmopolitanism has affected his poetry and Athens “the place he calls home”. He also comments on the appeal of Greek poetry abroad, noting that “more should be done in Greece to promote young poets and encourage translation as well as something to counteract the dismal publishing scene for poets” and on how poetry influences the way Greece is perceived by foreign readers.

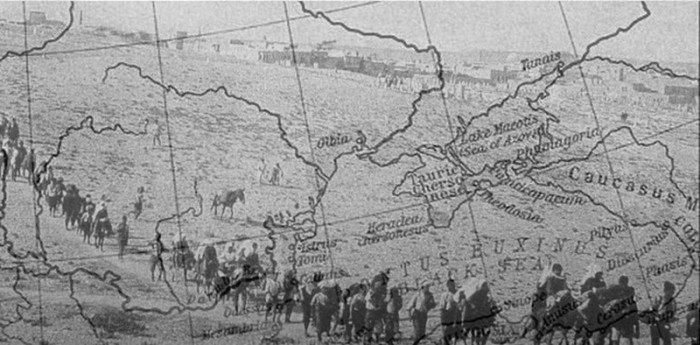

Your most recent collection The Black Sea – recently translated into Greek by Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke – is a long poem-cycle exploring the historic “great catastrophe” of the Pontic Greeks of Asia Minor in the 1920s through a series of “sonnet-monologues” or voices from the past. Why does such a major historic moment interest you?

I started thinking about voices speaking from the past when I discovered an old photo album from the 1920’s in a drawer in my father’s studio. My Grandfather was born in the city of Samsun, formerly Amisos, and so my family history was inextricably tied to the eradication of the Greek communities in Asia Minor. There were some recognizable family faces and lots of anonymous stares. The Black Sea, for me is a kind of cinematic experience. The poems began as “sonnets” because the sonnet reminded me of a snapshot––the shape, the concision, the compression of lines into a frame. It was a case of function dictating form. I didn’t set out to write The Black Sea with a concept.

I never much liked “concept” collections and I think American poets are now turning it into a cliché. Poets write poems, not books. But after five or six poems came about, I realized I wanted a more extended picture of what I imagined those people went through, and the historical context of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey was intense enough to sustain it. I decided to explore the region myself, to get closer to the landscape and so I took my motorcycle from Athens and rode through Anatolia, and then all the way back along the entire southern coast of the Black Sea, exploring villages, monasteries, and hanging out in the ports. If I ask myself whether I have the right to address such an issue, or whether I did justice to the memory of those people, I’m terrified.

As Anne Born eloquently put it, “there is sometimes a nicely melancholy tone to Papadopoulos’s work which puts him in the great tradition of poetic sorrows. But the elegance and flair in these poems makes the reader look forward to his next volume”. Where do you draw your inspiration from? What are the main themes of your poems?

I’ve said this before, so at risk of sounding repetitive, I truly believe poetry is about the same handful of subjects, again and again, through the millennia. What were Shakespeare’s themes? What did Sophocles write about? Dante? Rimbaud? Villon? Cavafy? Auden? Yeats? It’s all the same story, the human condition.

Your identity has been forged in a trilingual household that moved between America, France and Greece. Yet it’s Athens “the place you call home”. How has this cosmopolitanism affected your poetry? Does poetry actually constitute a kind of country for you?

Yes, a very strange country where one lives alone! It’s actually more like a “spiritual place“, a religion for atheists, a place which is yours and you carry with you wherever you are. Poetry is not a job, it’s a vocation and it’s a form of prayer– that is something Derek Walcott has written about beautifully. My father never spoke English and my mother, who is American, never spoke to me in Greek. In the beginning, their only common language was French. I’m fluent in Greek, but English is the language I was schooled in and it’s my mother tongue, it’s the language in which I first read The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, Crime and Punishment, Look Homeward Angel, etc. I’m basically an American poet who is Greek, but it’s a very schizophrenic scenario because I feel very much at home, and very much apart, in both countries. You don’t choose these things. I spent all my early childhood, adolescence and early adulthood living in Athens. It’s absolutely natural to me to describe the place I grew up in the language that I also claim as mine.

“Living in Athens can be like sleeping with a complicated lover; at some point, you will wake at dawn and lie there, eyes open, not quite sure who the person sleeping beside you really is. […] there is no logic in this place I still call “home,” even though I come and go, making and breaking promises with every return”. What does Athens represent for you? How has this city of contradictions changed over the years?

Athens is my home and the place I feel most comfortable in. Even more crucially, the house that my grandfather built in the 1920’s is still our family home and is the axis to which I continually return. Objects hold memories and much of my childhood is caught up in the streets of that neighborhood. A real city has to break through with a kind of honesty in moments, a revelatory flash in which the truth is briefly exposed– this could be a smell, a face, a shout or a peal of laughter, it can take any form. Athens does this, it breaks through to you if you pay attention. Faulkner said famously, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past“, which is how I see memory interacting with the present.

Athens is a massive contradiction, a city of immense beauty and incredible ugliness, it’s modern yet entirely backward, a European capital but also a Balkan backwater. I find most Athenians are unable to talk about the place objectively— the city suffers from an inferiority/superiority complex in equal measure, but I love every inch of it, even when I hate it, and no one can ever call it boring.

You have translated works of Greek poets – Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, Yiannis Ritsos and Kostas Karyotakis among others – while you are the editor and co-translator (with Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke) of Derek Walcott’s Selected Poems into Greek. Is there an interest in Greek poetry abroad? Does this poetry influence the way Greece is perceived by foreign readers?

There is a great interest in Greek poetry abroad, at least by people who read poetry (but those are sadly quite few) and there are some excellent translators at work. Greek literature in general, including the Classics is read with interest, but most of it is centered on classicism, two Nobel laureates, Cavafy and Kazantzakis. Writers such as Karyotakis, Kalvos or Solomos are almost entirely unheard of outside Greece. This is a problem with Greek artists as well, who are rarely considered alongside their European counterparts. Contemporary Greek literature is relatively unknown outside of Greece with the exception of some recent efforts by Greek poetry festivals and publications as well as a number of anthologies by foreign presses and universities. More should be done in Greece to promote young poets and encourage translation as well as something to counteract the dismal publishing scene for poets. The fact that Greek poets have to pay publishing houses to produce their own books is unforgivable.

But Greek literature has definitely shaped how the country is perceived, and that goes all the way back to Homer. That poetry also exerted and enormous influence on other poets, from Byron to James Merrell for example. Even Derek Walcott’s Caribbean has been deeply marked by a sense of “Greekness“. Kazantzakis created Zorba, a poet at heart, and that romantic persona has come to embody the idealized sprit of Greece. It’s part fantasy and part reality. I just hope we don’t lose that joy as we descend deeper and deeper into a culture of worry and distress.

Are there any new ventures underway? What are your readers to expect in the near future?

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke’s translation of The Black Sea was recently published by Kastaniotis and I’m finishing up a new collection of poems in the USA. I’m also working on some prose, an experiment in process, but where that will lead remains to be seen….

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

Read also: Grèce Hebdo – Stéphanos Papadopoulos: «La beauté exige notre vigilance» (Interview in French)

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE