Τhanos Gogos spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest poetry collection Dakar, “an inner journey during which the lyrical subject is searching, inside himself, for the road that leads to peace”, emphasizing on “the similarity of love and revolution, rooted in the concept of left wing melancholy”. He also comments that “drawing the lines between generations is not an easy task”, given that “literature is a highly complex, multi-layered, dynamic system”, and concludes that “we have to invest more into finding ways to promote good poetry and funds to publish it”. “We strive, we adapt, and we are ready for any difficulties that may occur on our way because we believe in literature and we think the world would be less meaningful without it. A publishing house is a megaphone for a poet. And we like poetry to be present and loud”.

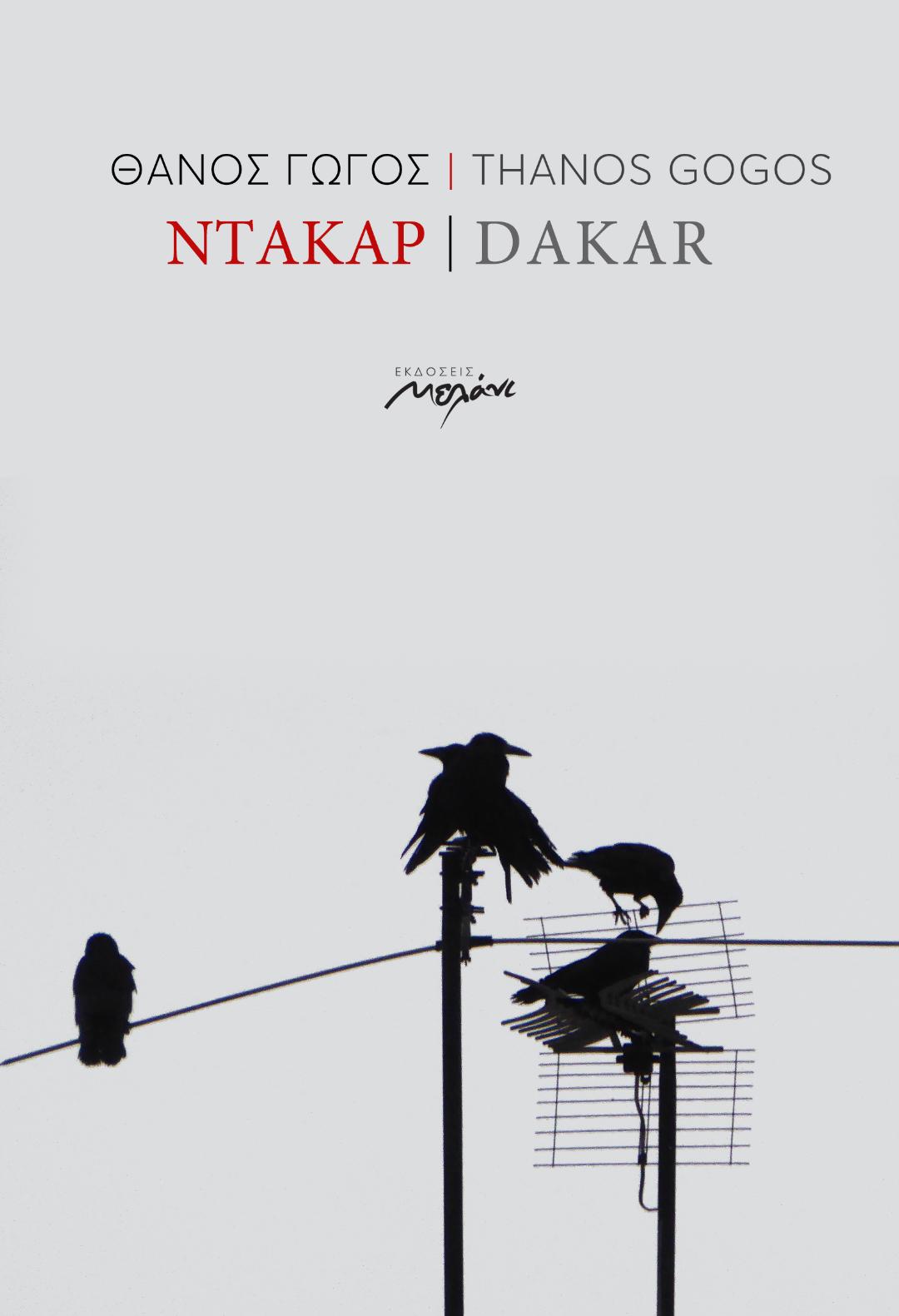

Your latest poetry collection Dakar was quite favorably reviewed upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

Dakar is a book that I’ve been writing for the last four years. It was published by Melani in 2020. Just like my previous book, Glasgow, Dakar is also a conceptual poetry book. Even though it can, aesthetically, stand alone, as a whole, Dakar can also be perceived as a continuation of Glasgow. In Dakar, I build a world of isolation, retreat, reduction. It is an inner journey during which the lyrical subject is searching, inside himself, for the road that leads to peace. Dakar constitutes the detached peace after the storm of Glasgow.

Are there recurrent themes of reference in your work? How is the notion of the ‘political’ defined in your poems?

Recurrent themes of reference in both Glasgow and Dakar are the senses as a basis of perception, and traveling. I like to explore avant-guard writing in a contemporary way. In Glasgow, I explored, both in the book and in real life, experience and overload on senses, as means of creation. Before writing Glasgow, I traveled a lot, saw and experienced a number of strange things. That escape into the intensity, into the noise, was the fire that fueled the destructiveness and passion of Glasgow. When I was writing Dakar, I retreated into isolation, and my journey was solely an inner one. I used the mature senses to produce intuitive thinking.

Of course, these are not two separate, opposite ways of functioning. They are in a dialectical relation. The notion of the political in those two books is, consequentially, dialectical too. If Glasgow was a post-anarchist, cynical symbolic destruction of all values, Dakar emphasizes the similarity of love and revolution, rooted in the concept of left melancholy (Vassilis Lambropoulos has used the term to describe the generation of 2000). It’s an idea that it often happens that a person stops believing in something, or loses their faith in it, but still can’t let go of it.

In her review of the book, poet Anastasia Poulou commented on an increasing minimalism and abstraction from one poetry collection to the next. What purpose does language serve in your writings?

Poetry, for me, is language, like photography is the image. Dakar was all about exploring minimalism, about trying to reach the maximum potential of a single word. In the next book I may follow another form. I like every book to be different but generally I care and work a lot on how to express something in rhythm and with using the right words.

You are co-editor of ‘Thraka’ literary magazine and editions, which have contributed to new poetic voices being heard and published. Tell us a few things about this venture of yours.

Thraka is a publishing house based in Larissa; we also have a printed and online magazine and we organize the international “Thessalian Poetry Festival” and the European residency Project “Ulysses Shelter”. In Thraka, we publish both established and emerging voices. To us, it doesn’t matter if you have published ten books or none, if you have won awards or not. We highly value writings both by established poets and by the emerging ones. Our only criteria are that you have something to say, and that you know how to put it in writing in a way that is of high aesthetic quality.

We believe that Greece is full of talent, full of amazing poets and authors, and we want to make the process of emerging as an author a bit easier for them. That is why, besides the constant pursuit of new beautiful and brave pieces for the magazine, we also have established an award for the best unpublished manuscript by an author who hasn’t previously been published. It’s called “Thraka Award”, and for us, it is not just an award, but also a statement – by founding this award, we are expressing our belief in the value of what’s coming in Greek literature. We are thrilled by the quality of the manuscripts we have received, and wondering how many more amazing poems exist in Greece, waiting to become books.

So, I could say that Thraka’s primary focus is contemporary poets of the younger generation, but we also publish books by already acclaimed and established poets, while, in Thraka magazine, we publish essays and prose too.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, festivals, just to mention a few. How is this strong civic awareness to be explained?

Poetry has the ability to put a world in a few lines. That’s why, in my belief, it appeals to many people. Poetic writing has the potential to express such a variety of ideas and feelings in such a small space – whether it’s the most tender love poem, or the harshest societal critique. That is why, I believe, everybody can find a poem they like, even if they don’t care about poetry in general.

Vassilis Lambropoulos has used the term ‘left melancholy’ in order to characterize Greek Poetry of 2000, ‘a combination of resignation and resilience’, ‘a political disposition driven by refusal but not resignation, defiance but not defeat”. Are there some unifying traits that may enable us to talk about a new ‘generation’ in poetry and a ‘left melancholy generation’ in this respect?

I value professor Lambropoulos’s research work on contemporary Greek poetry very much. I think of it as a lucid and successful attempt to capture what’s happening now and to find a way to systemically approach it, and analytically present it using a strong theoretical background.

Drawing the lines between generations is not an easy task, but it’s necessary for the understanding of literature. Of course, finding the one, specific, most important, line of divide between generations would not be possible, since literature is a highly complex, multi-layered, dynamic system. So, the task was, I would say, to be relatively arbitrary in an objective way, and I think Lambropoulos did an amazing job. I reckon left melancholy is a concept specific enough to grasp the feeling of the generation, but also broad enough to be used in systemically approaching a broad variety of different poetic manifestations.

How do you respond to those that argue that the recent socio-economic crisis has broken the ties connecting readers with the choices and orientation of traditional publishers, creating an aesthetic and intellectual space that remains to be filled?

Publishing practices have taken so many different shapes and forms nowadays. I’m not sure if the ties between readers’ preferences and traditional publishers’ choices are broken, but for sure we see a new map in the field, because there is such a variety in publishing houses regarding aesthetic preferences, ways of approaching the readers, etc. We have big, commercial publishing houses with an appeal to the broader audiences but mainly in prose and we have new, small, more specialized publishing houses. We have also witnessed some activist and alternative publishing. I believe there is something for everybody. So now that I think about it, yes publishing good poetry is not anymore a privilege of the big, traditional publishing houses. Neither is publishing bad poetry.

From what I’ve experienced, the economic crisis hasn’t affected people’s love for reading. And when there is a will, there is a way. We are still reading, we are still buying books. Literature offers us balance in emotionally turbulent times and a means of struggle in socially dynamic times.

In addition, I’d like to point out that the price of books in Greece is much lower than what I’ve seen in some other European countries. Luckily, as a society, we still perceive the ability to afford art and knowledge as a necessity, and a human right, and not as a luxury.

So we have to invest more into finding ways to promote good poetry and funds to publish it as it happens outside Greece and not to ask from writers to pay thousands of euros to publish their books for publishers’ safety. If publishing houses move to this direction, we will have fewer poetry collections but of higher quality and much more dignity in this respect.

The situation for publishers, especially smaller ones or ones that are not Athens-based, is far from perfect. It takes a lot of hard work, almost no free time, and really, if your heart is not beating for literature, it will be very hard for your publishing house to survive. But we strive, we adapt, and we are ready for any difficulties that may occur on our way because we believe in literature and we think the world would be less meaningful without it. A publishing house is a megaphone for a poet. And we like poetry to be present and loud.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Fotis Natsioulis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE