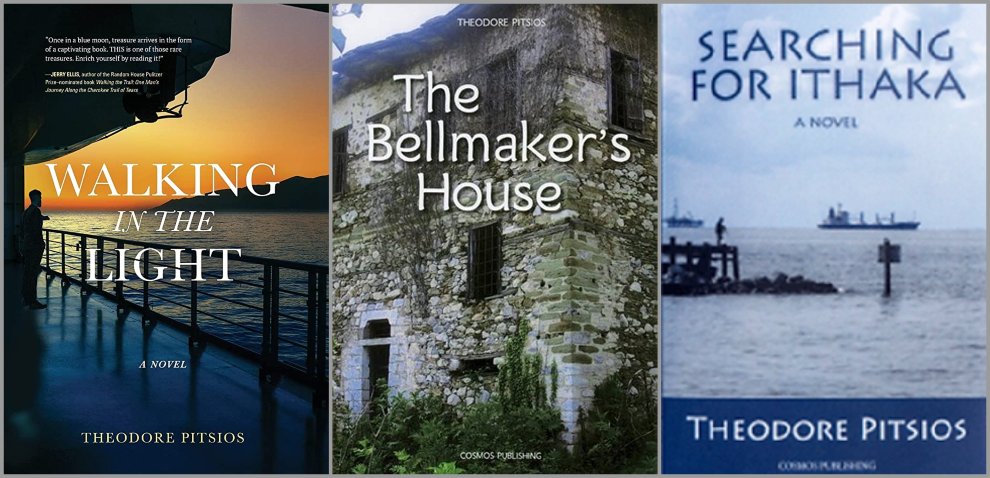

Theodore Pitsios was born in Tsagarada, Greece, he graduated from the Maritime Academy and sailed as an engineer in the merchant marine. After some time in Nassau, Bahamas, he embarked on his own American Dream, beginning in West Palm Beach, Florida, and ultimately settling on the Gulf Coast. He splits his time between the US and Greece. He is the author of The Bellmaker’s House, Searching for Ithaka, and Walking in the Light, all aiming to bring new insight into the immigrant experience.

Your latest writing venture, Walking in the Light, “follows one man’s odyssey as he struggles to redefine the meaning of home”. Tell us a few things about the book.

The story is set in the mid-fifties, not long after the Cuban missile crisis. We still had black telephones plugged to the wall and we still had to get off the couch to change the channel on the television set. And speaking of television, Elvis Presley’s gyrating hips were as risqué as a performance would get. It was a time when the prestige and respect among the people of the countries around the world was at its highest. The prosperity and the comfortable living of the United States was legendary. “Money flows on the streets, and they tie the dogs with the sausages over there,” the simple folks of the other countries used to say.

The book is about those immigrants who are coming, legally and otherwise, to this land where “they tie the dogs with the sausages”, hoping to get a small piece of that prosperity for themselves. The story takes place in Little Havana, an area of Miami, in South Florida. It is narrated by Kostas, the protagonist. He is a twenty-five-year-old Greek merchant seaman with a ninth-grade education, who, like the many before him, took at face-value the overembellished stories of success of those who preceded him.

Being the author of three novels so far, what are the main themes your writings touch upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

All of my books so far are about people who migrate to the United States of America and about their struggles for acceptance in their new land. It is also about their efforts to prove to those at home that they had made the right choice.

You have said, “Since I’m an immigrant in the United States, I write about the lives of immigrants […] In my writing, I’m attempting to say something about the lives of ordinary people in ordinary people’s language.” Are there autobiographical elements in your books?

The books are not autobiographical; however, they are inspired by recalling past events of my life and the lives of people I’ve known. Taking that into consideration, one may say that there are indeed “autobiographical elements” in my books.

What about your personal story from Tsagarada, Greece to becoming a merchant mariner, a businessman, and a successful writer?

I’m in the process of putting on paper some events of my youth and of my later life while I can still remember them. Hopefully, a book with all of that reminiscing will see the light of day sometime in the near future.

Your stories seem to bring new insight into the immigrant experience. More generally, how does literature help enrich our understanding of our personal as well as our common past?

By reading stories about the lives of immigrants from countries around the globe we become aware that all people, regardless of place of origin or the color of their skin, have the same dreams, hopes, and aspirations.

In recent years, American literature has seen the emergence of important writers who live in the US as first-generation immigrants. Would you say that the particularities of origin and language are conducive to the creation of a distinct literary style?

Depending on what age the “first generation” immigrants are when they come to this country, they inevitably bring with them the sense of values and order of life’s priorities of the country they left which will be reflected in the style of their writings.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

![Literary Magazine of the Month: [FRMK] and its Ten-Year Anniversary Issue ‘Tenderness-Care-Solidarity’](https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/04/frmkINTRO2-1-440x264.jpg)