Thodoris Rakopoulos was born (1981) in Amyntaio and studied in Thessaloniki and London. He has published three books of poetry (Fayoum, Mineral Forest, The Gunpowder Plot), one of short stories (Bat in the Pocket) and one as part of a poetry triad (You Know the End). He has been awarded the State Award for Debut Writer for his first book, while for the others he was nominated for various awards (State and the Diavazo magazine). He maintains the blog Africa by another name. His poems have been translated into seven languages. His next book is the poetry collection On the National Highways. He is an Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo.

Thodoris Rakopoulos spoke to Reading Greece* about his poetry and prose writings noting that “a recurrent theme is time and its marks”, “the temporal domain and its puzzling nature”, while commenting on his attempt to always “build a story based on imagery or at least suggestive details grounded on recognisable references”.

As to the relation of literature to the world it inhabits, he argues that “in felicitous cases, poetry is there to unsettle the conformity”, and adds that across his work, “a specific theme includes politics and the scape of the political”, while a recurring theme is “migration in all its forms, often connected to loss”. He concludes that “the most important thing that Greek literature needs now is institutional ambassadors: promotion of literary work written and published in Greek to anyone interested abroad”, as well as the funding of academics “to continue teaching Greek literature in academia around the world”.

Three poetry collections and a short story collection so far. What are the main themes your writings delve into?

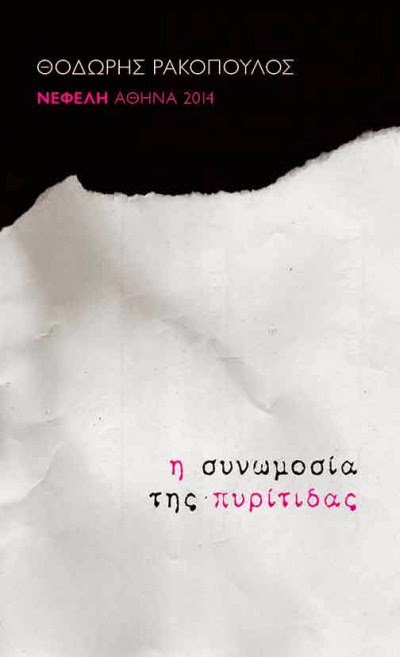

A recurring theme is time and its marks. Whether it is captured and framed in pictures and photographs, whether it is negotiated through alternative histories, whether it is trapped in magical narratives, I reckon the temporal domain and its puzzling nature is where much of my work focuses on. I do think a book has to have a loose theme, by the way. I worked on one quite specific thematic in The gunpowder plot (Η συνωμοσία της πυρίτιδας), where I tackled conspiracy theories and alternative scenarios. To do that, I employed either forms of fantasy literature (especially references to Verne), or as if conspiratorial narratives or vignettes on the lives of Jehova’s Witnesses. The result is a satire permeated with both humour and drama (so I have been told – and I’m happy about it.)

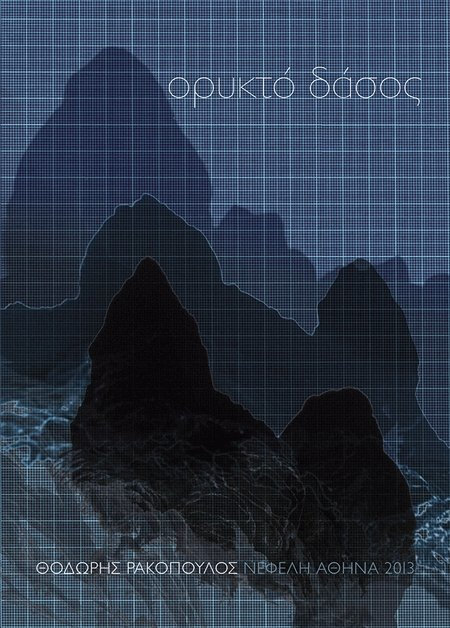

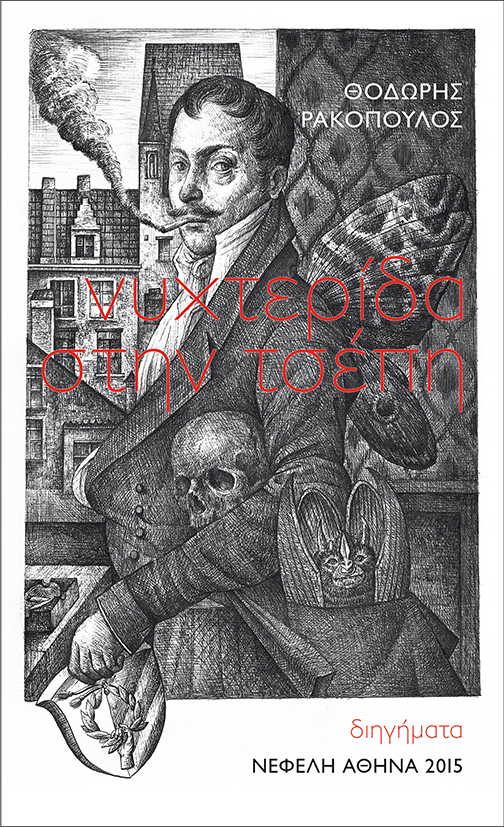

Memory’s haziness (hence the temporal inertia point) is very central in Fayoum (Φαγιούμ), as is the case in my short story collection Bat in the pocket (Νυχτερίδα στην τσέπη). Fayoum in particular is almost entirely composed of poems that ruminate on visual material, which performs the impossible task of capturing time (photographs, paintings, identikits, etc). In Mineral forest (Ορυκτό δάσος), the theme of the book is memory again, but in more mythical renderings; it is, after all, my most ‘poetic’ book. The former part of Mineral forest contains references to a hedgehog, supposedly the listener of the stories narrated. I can’t but admit that many of the poems that I published in this book, as well as The gunpowder plot are influenced by my work as an academic anthropologist (myth, an attention to the vignette, even the vocabulary drawing from the ethnographic record.)

Bat in the pocket presents 20 different stories involving places across the realm of my own experience (from London to Cyprus), where animals of all sorts play a minor part in each story, accentuating the paradox of the central circumstance. Again, the fuzziness of the actual event, as well as drama of overlapping temporal domains are central here – but the book is read as a conventional set of short stories, too. My last book, co-authored with poets S. Mitas and A. Psaltis, also delves in the impossibility of rendering and saving time.

An internal structure seems to govern the poems included in your poetry collections, enabling the reader to converse with them from the beginning to the end. What purpose does this structure serve?

Very insightful question and point… I wish I were able to answer in ways that won’t sound too self-centred. I’d rather leave the answer to the potential reader, as essentially poetry happens when the reader receives it as such. I could only note that I operate on what can be called a narrative mode: whether this is cinematic or ethnographic or endo-poetic it depends on the poem and its theme, but I always try to build a story based on imagery or at least suggestive details grounded on recognisable references. When I moved into trying my hand with a short story collection, it felt like a smooth transition, as I worked on stories that begged for prose narration.

My forthcoming poetry collection At the national highways (Στις εθνικές οδούς) returns to poetry with a decidedly narrative construct of each poem, which always tells a story – that could not have been narrated in prose, however. The book returns to satire and social criticism, while being –as always- primarily a narrative poetry book. The theme, as the title suggests, is playing with the grandiosity of national myth and the mundanity of actual experience. I guess that is a good definition of the way I work as a poet: I’m telling stories that can only be narrated in poetry form.

“The bet for a poet is to move beyond language through the language“. What role does language play in your writings?

There is language-centred poetry for sure, but mine is far from that. Language themes are central to my work in that the language I write in necessarily becomes a travelling toolkit, as I live away from Greece. It becomes the real site of belonging – not in a Heimat kind of way, but as a means of contributing letters from afar. In terms of the actual point I was trying to make through that sentence you cite, I meant that poets are in the certainly ambivalent (and often unhappy) position of working on language, something we all possess – the very framework that makes us what we are as human beings, in fact. The poet works with material we all use, so her/his mastery is to transform it beyond recognition, and achieve that level of otherness, even uncanniness, that estranges the reader. Again, I am not a linguist and only have a very cursory understanding of, say, Jakobson’s points on the metalingual, but I think that the reflexive aspect of language that good poetry achieves is a constant goal for poets.

In Fayoum there seems to be a strong influence from the cinema. How does your poetry communicate with other arts?

Indeed, it could be argued that my work is cinematic. My list of favourite films is endless and I’d rather talk about auteurs of cinema than anything else, really. I guess I’m yet another filmmaker manqué – or possibly at best film critic manqué. But I mean, I have literally transported images or thoughts by Pasolini, Angelopoulos, Kiarostami, Kaurismäki into my poetry. As far as the visual arts, the same goes for references in my work to artists as different as Mantegna and Caravaggio, as well as poetic transmogrifications of work by Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud. But I’m getting ahead of myself, name-dropping… The point is that my poetry is in constant conversation with other arts, which I consider as much a source of inspiration as written poetry is.

You have characterized literature as both a moral challenge and a political venture. What is the relation of literature to the world it inhabits? What does it mean for literature to be political or a-political especially in times of crisis?

An age-old question, and given the provocative statement you refer to, I am guilty of complicating it further. Obviously, all phatic communication is in some way potentially “political” in that it operates within a social framework and cannot avoid connotations and significations that are pregnant with ambivalent meaning. Actually, ambivalence and nuanced discourse are central to the making of contemporary poetry – and certainly my kind of poetry. Mimicry, irony, sarcasm, tongue-in-cheek statements, as well as post-lyrical dramatics, are all forces we use (I, for one, certainly do) to negotiate the complicated weight of poetic language. All the above are political tools, in many ways. The politics of poetry, at least as I see them today, are a defensive trench, really. The poet shelters their world with these dugouts, as language, the only channel for poetry, is inhibited by all sort of forces of power: it actually transmits and confirms power in the everyday in ways we don’t even notice. So, in felicitous cases, poetry is there to unsettle this conformity. I hope. As far as crisis – to think that the ‘Greek’ ‘crisis’ is over is utterly ridiculous: it is deeper now than it has ever been; discussing it poetically is inevitable if someone experiences its circumstances (not all do: a small minority among us live undeterred by any ‘crisis’, and for the ruling classes of Greece the crisis has generally been an opportunity for enrichment.)

To go back to your first question here, a propos of giving an example of the ‘political’ in literature… Across my work, a specific theme includes politics and the scape of the political, and a recurring theme is migration in all its forms, often connected to loss. I discuss migration both historically (I come from an overwhelmingly emigrant family on my father’s side, while my mother is a Greek-Cypriot refugee) and synchronically – I am an immigrant myself, albeit with a much cushier life than my ancestors. In that way, this theme rises organically from experience and inhabits my poetic universe. But most crucially, I think migration is the main issue of our times and witnessing the sheer violence of posing boundaries to human movement is a political and existential mantra for our times. Loss (emotional and material) more generally is particularly central to my writings – and maybe migration is one of its more palpable expressions.

You have argued that the term ‘generation’ is an extremely problematic tool if we want to describe the current literary landscape. Why is so?

This was in an essay and thanks for bringing it up, as it is an issue close to my heart. I won’t do justice to the essay’s argument here, as the –hopefully nuanced- analytical narrative of an essay cannot be reproduced in a different context, especially in an interview. But, as briefly as I could put it: it seems to me that ‘generation’ is not a proper analytical tool to comprehend the polyvalence of a series of different voices whose only common circumstance is that of temporal coincidence. Granted, we have been brought up at the same time period, those poets of a similar age, but this cannot constitute a frame of common experience necessarily – especially in the hyperdiversity of our times. ‘The crisis generation’ poetry is not Bakhtinian polyphony, but an array of different people (I am happy to consider a few among them friends) whose poetic universe is penetrated by a common context – which, note, does not mean a common experience. Having said all this, I am not a literary studies scholar, so it is possible I am talking pompously here, going out of my turf.

How do Greek writers relate to world literature nowadays? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

I am, in theory, in a good position to answer this question, as I have been living abroad in the last 15 years of my life. Only in theory though, as I have been too modest and shy (or just plainly amateur) to promote my work in the countries I have lived in (Italy, South Africa, and especially the UK and Norway for many years). In all honesty, it never made sense to me to proactively promote my own work abroad –this could be the work of other agents in literature, a point to which I’ll return in a sec.

I have followed some of the local poetry scenes but never got involved – this is not least because I feel my own scene, so to speak, is in Greece and Cyprus, the countries where Greek is read most. I guess this bit answers the latter question, as the local interweaves with the global in ways that are necessarily grounded in the framed circumstances of “national” locality. It is unfortunate, but it’s true. It is particularly unfortunate for someone like me, as I have always been openly anti-nationalist and vehemently internationalist in my life, work, and understanding of the world. Nevertheless, in my tiny part, I wouldn’t subscribe to any national narrative – and in this I am saved mainly due to my origins (Western Macedonia on my father’s side, an area heavily influenced by a dialect of the language of North Macedonia, and Famagusta on my mother’s side, then a bi-lingual and now a ghost city lost to the Turkish occupation, whose ex-residents brought their own dialect of Cypriot Greek elsewhere, as refugees). Both Macedonia and Cyprus, as “problematic”, critical margins to national identity, are saved from the Athenocentric national narrative due to the specificities of their local languages, which especially in the case of Cypriot-Greek have been a heavy influence on me.

Now, and very briefly, regarding the former question: I know writers in Greece read a lot of foreign literature, either in the original (especially English) or in translation. This is priceless but we should be weary of the exhaust fumes of influence. In poetry you don’t see much of those, as we work on two plains that can barely interpenetrate: it is important to read poetry in other languages, but it is your own language’s poetic tradition that you are an active part of, as poetry is language-conditioned more than prose is.

Clearly, the most important thing that Greek literature needs now is institutional ambassadors: promotion of literary work written and published in Greek to anyone interested abroad. The loss of several university seats on Modern Greek Studies has been a major problem; needless to say, the state should fund academics in this environment to continue teaching Greek literature in academia around the world.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE