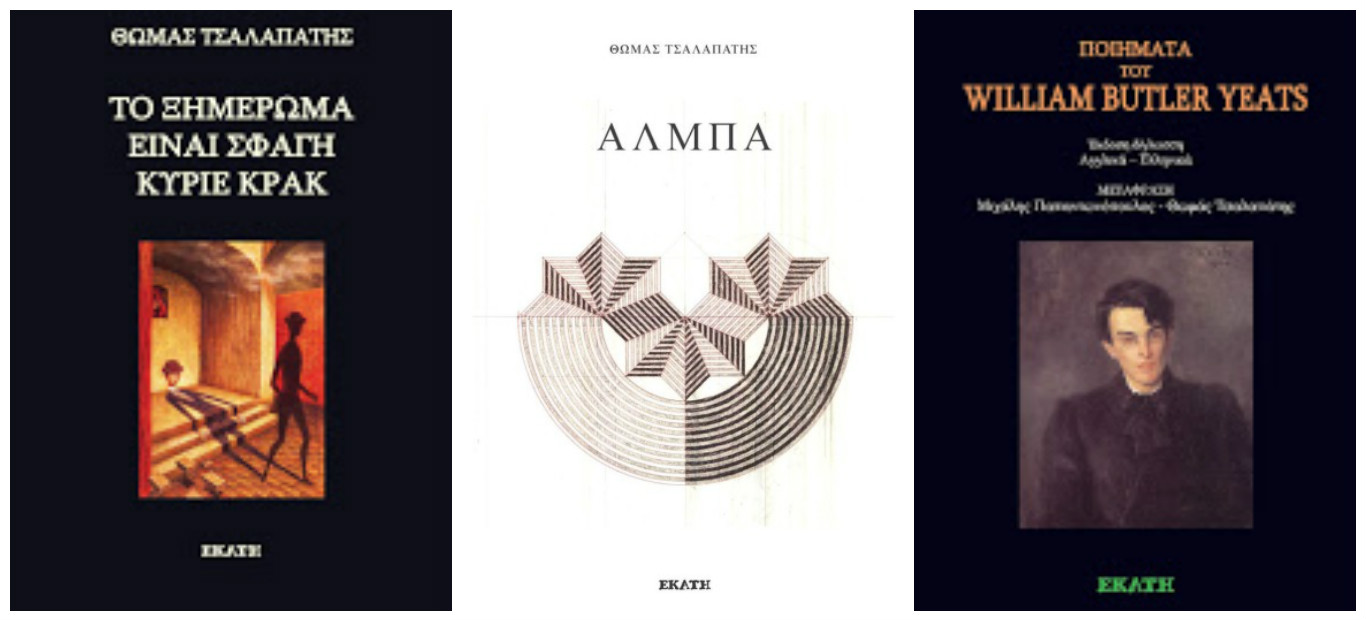

Thomas Tsalapatis (1984) studied theatre at the University of Athens. His first book of poems Το ξημέρωμα είναι σφαγή Κύριε Κρακ [The Dawn Kills, Mr. Krak] was published in 2011 and received the National Literary Award for best new writer the following year. His second poetry collection titled Άλμπα [Alba] was published in 2015. He has also published a Greek translation of poems by W.B. Yeats and writes for various papers and journals.

Thomas Tsalapatis spoke to Reading Greece* about his two poetry collections, the themes his poetry touches upon and the binding thread between poetry and theatre. He discusses the role a poet is called to play nowadays noting that “it is a poet who will propose a new (and every time anew) way of handling language and words, and thus reality” and commenting on the necessity of poetry for the debunking of stereotypes.

Asked about the extraordinary burgeoning of poetry during the economic crisis, he comments that “the crisis itself constitutes a major disruption in the superficial historical continuum of the last forty years in Greece; a landmark of events, triggering a change of perspective and even mood”. He concludes that although “it’s too soon to talk of a new generation of Greek poets, let alone identify many common traits”, it is undeniable that “poetry has come to the fore claiming the space it deserves, the intensity of its own nature”.

You have published two collections of poems that have received rave reviews. How do you define your poetry? What are the issues your poetry touches upon?

I believe that, in reality, poetry itself – each poem – amounts to its definition. Every poem, if it be worthy of itself, seeks to present a personal version of the phenomenon. A literary, scientific definition would seem to me very restrictive, almost suffocating. For me, poetry constitutes a field identified as such by its creator. It’s a field that may encompass everything, all forms of speech, even if they don’t directly evoke poetry. From the moment the writer decides to define his work as poetry, it is poetry. This does not necessarily mean that the work seeks to draw qualitative value from the label. Poetry is not a value, it’s a state. Thus, by incorporating something into this state, what you are asking is to be judged on the basis of its recorded history. The only restriction to poetic freedom is its attainment.

I am not really sure as to the themes of my poems. You only identify them after the poem is written. So, in retrospect (as regards both my books), I would say violence, time, humor and the absurd are the keystones (and not necessarily themes). Yet, interpretation lies with the reader.

“A poet is the manager of darkness that illuminates the black light. Poetry constitutes the underlying cause and at the same time, its accomplishment and its negation”. What is the role a poet is called to play nowadays? Is there a way to debunk the stereotypes that are usually associated with its image?

I believe that the role of a poet remains the same throughout time. It is a poet who will propose a new (and every time anew) way of handling language and words, and thus reality. The limits of the world are defined by the limits of our language and I believe that a poet is the key-holder of these limits. Stereotypes have always existed and will continue to exist. It is a way of getting things over and done with quickly. Especially when it comes to states of emergency – like poetry – these stereotypes act as a parody, almost reassuringly, as regards the state of emergency. We are thus faced with the paradox that the more – in number and intensity – the stereotypes are at a given time (including those who embody stereotypes, either as attitudes or texts) the more necessary poetry becomes.

Encore, the new production of Attis Theatre, based on your poetry, premieres on November 25th. Where do theatre and poetry meet? What is their binding thread?

The relationship between poetry and the theater is as old as are both art forms. Poetry, which began as an oral genre, carried the theatricality of narration and recitation, while the theater, as something detached from ritual, has always been defined by textual abstraction which brings speech close to poetry. In fact, realism in theater has only been a short interval (lasting about a century and a half) in the history of theater. What Theodoros Terzopoulos and Attis Theater have proposed has been the re-invention of set limits, through body and breath, through the actors. Poetry maintains a privileged relationship with this kind of theater.

You have said that “poets of the 1930s are the only ones that could be described as a ‘generation’ constructing what is still considered today to be the dominant narrative of a more sophisticated bourgeoisie”. Could you elaborate on that?

The poets of the 1930s were the only generation (possibly with the exception of that of the 1880s) that formulated a concrete narrative for viewing the present, the past and Greek identity. This narrative, including the symbols it employed in poetry or painting, the way it approached tradition and so on, has remained intact to the present and is still expressed in various forms. Those poets had a key role in the “programming” of this generation. Our contemporary aesthetic sense, to a great extent, originates in and incorporates that generation. Thus, the poetry of the 1930s has survived to the present, even indirectly: “We are the interwar years, I tell you, incurably the interwar years” as the great poet Byron Leontaris wrote.

Karen Van Dyck, editor of Austerity Measures, has characterized the new generation of Greek poets as “multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational”. How would you comment on current literary, and more specifically poetic, production in Greece?

The truth is that there has been an increase of worthy poetry books over the last 10 years; new and quite different voices, initiatives in novel directions, diverse ways of approaching contemporary poetic tradition. I believe it’s too soon to talk of a new generation of Greek poets, let alone identify many common traits, given this great variety described by Karen Van Dyck. Yet, and despite definitions, poetry has come to the fore claiming the space it deserves, the intensity of its own nature.

Since the crisis began in 2008, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares. How do you respond to those that talk about a “poetry of the crisis”? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

The crisis itself constitutes a major disruption in the superficial historical continuum of the last forty years in Greece; a landmark of events, triggering a change of perspective and even mood. This obviously does not mean that it has affected all writers (let alone in the same way). We cannot however deny that the crisis remains present – even through its absence – in all these writings. The young people who began publishing their poems in the midst of the crisis did so concurrently with the rising popularity of Facebook, Twitter and public discourse through the social media. This has, in turn, affected the whole process of writing and reading and thus all these young poets; and even if poetry itself has not been affected, the terms governing its propagation certainly have. A new book or a poetry event has become much more easily accessible. Literary critics (who in most cases presented books rather than reviewed them) are being bypassed. There has been a shift vis-à-vis the power, the speed of information as well as the extent of poetic noise produced.

All things considered, poetry remains a proposal for a new way of viewing reality. And this demand for a fresh approach can be easily applied to other fields as well, that is to art, human relationships and politics.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE